BY EMMA BAILEY What does it mean to be “human”? What is it that separates our consciousness from all the other creatures of Earth? Is human consciousness quantifiably superior to the beasts of the field? We could go back and forth on this topic all day, but you don’t see birds debating Derrida or solving long division problems, and yet there is something exquisite about the Zen-like simplicity of their existence. Why do humans insist on complicating things?

BY EMMA BAILEY What does it mean to be “human”? What is it that separates our consciousness from all the other creatures of Earth? Is human consciousness quantifiably superior to the beasts of the field? We could go back and forth on this topic all day, but you don’t see birds debating Derrida or solving long division problems, and yet there is something exquisite about the Zen-like simplicity of their existence. Why do humans insist on complicating things?

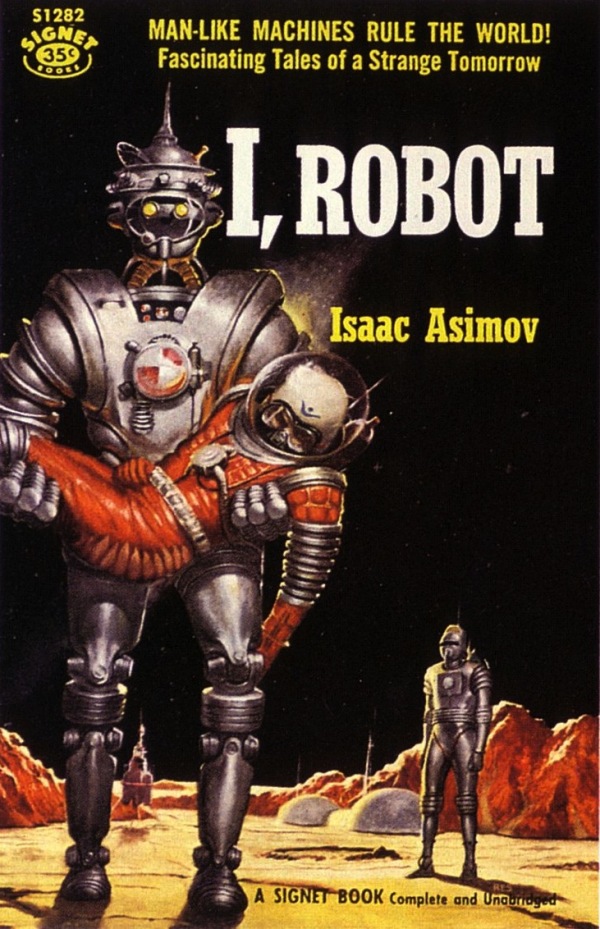

In a blink of time’s eye, the dinosaurs became extinct, mammals came down from the trees, and mankind developed a unique and highly specialized  intelligence. While it’s true that other animal species possess a vast spectrum of extraordinary abilities, many superior to ours, none hold the capacity to create a mechanical counterpart, or “thinking” successor — a thought both awesome and chilling. No one illuminated the quandary of human/robotic relationships better than Isaac Asimov.

intelligence. While it’s true that other animal species possess a vast spectrum of extraordinary abilities, many superior to ours, none hold the capacity to create a mechanical counterpart, or “thinking” successor — a thought both awesome and chilling. No one illuminated the quandary of human/robotic relationships better than Isaac Asimov.

In his short story collection I, Robot, Asimov attempted to codify “Three Laws of Robotics”, which were intended to govern the behavior of intelligent automatons. As robots integrate further into our daily lives, the importance of such laws is increasingly called into question. With drones in the sky, automated appliances in our homes, and other robo-beings running important systems across the world, it’s clear that we’ve already ceded control of much of our lives to the machines. True artificial intelligence may still be several decades away, but as robots move further from mere human-helpers and closer to mankind’s sentient mechanical counterpart, we find ourselves at a crossroads.

A fear of thinking machines is rooted deeply within our culture, and the risks of super-intelligent computers have been explored by a number of sci-fi writers. But again it was Asimov who laid the groundwork for our contemporary understanding of the human/robotic convergence. Asimov’s laws, as the John W. Campbell anecdote goes, flew in the face of the prevailing winds of robot fiction. Prior to the 1940s, robot stories essentially copied Frankenstein: Scientist builds robot, robot runs rampant, sad ending follows. Asimov identified the presence of a more profound sense of alienation from our robo-brethren, a terror ingrained in our own hard wiring.

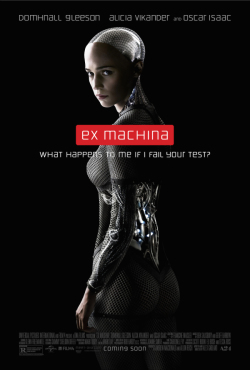

A number of current films play on his original ideas – Chappie, The Avengers: Age of Ultron, Ex Machina and the upcoming Terminator: Genisys all explore human fears of AI  run amok. Ex Machina, perhaps most expertly, delves into the complex emotions that arise when one encounters an intelligent (and attractive!) humanoid. Invoking the effect which psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch termed “the uncanny valley,” the film probes the instinctive revulsion we have when robots look like us and mimic our thought patterns, without actually being one of us.

run amok. Ex Machina, perhaps most expertly, delves into the complex emotions that arise when one encounters an intelligent (and attractive!) humanoid. Invoking the effect which psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch termed “the uncanny valley,” the film probes the instinctive revulsion we have when robots look like us and mimic our thought patterns, without actually being one of us.

Indeed, the film explores concepts of self-awareness, sexuality, attraction and manipulation via the stunning android Ava, whose capacity for “intelligence” is constantly under scrutiny. Living with her creator in a massive, fairytale research facility, she is the focal point of his fascinations and a vehicle through which he intends to study the (male) response to a gorgeous, albeit synthetic, life form.

Ex Machina marks Alex Garland’s directorial debut, and he arrives on the sci-fi scene with a fully formed vision. An appropriately chilling score and impressive lead performances “flesh out” the story, which looks to the future while simultaneously referencing great AI movies of the past. In the film there are echoes not only of Asimov but of other pictures that point to eventual rise of AI and its threat to humanity. In the film we cannot fully recognize Ava as one of our own, and yet we project our desires onto her anyways. We can never know if she is more human or more machine, and in the end it might not really matter. The shocking final scenes leave viewers scrambling for clues – possibly even searching for traces of the cold, unfeeling, and even robotic components of their own psyche.

Chappie and Avengers: Age of Ultron also telegraph our fear of an AI planet. Chappie tells the story of a police-bot, whose unique wiring imbues him with the capacity for free thought. Naturally, as the only member of the robot police squadron with a human “brain,” trouble follows him as he develops from a child-like droid into an “adult” robot. Die Antwoord’s Ninja and Yolandi bring street cred to the film as futuristic gangsters, Hugh Jackman rounds out the cast as a gritty urban villain (con mullet). Ultron’s nefarious super-droid leaves audiences with a clear message: smart  robots mean danger, danger Will Robinson. A cut-and-dry depiction of a robo-baddie, he isn’t much deeper than his chrome exterior, even as he pummels the Avengers with dark jokes. It’s a popcorn AI flick, but what it lacks in profundity it makes up for in tight costumes and giant explosions.

robots mean danger, danger Will Robinson. A cut-and-dry depiction of a robo-baddie, he isn’t much deeper than his chrome exterior, even as he pummels the Avengers with dark jokes. It’s a popcorn AI flick, but what it lacks in profundity it makes up for in tight costumes and giant explosions.

There is no doubt that our instinctual terror towards AI stems from a genetic memory of the struggle between the Neanderthal and the Cro-Magon to move from Alpha Human to Beta Human 1.0. Somewhere down the evolutionary line it made sense to recoil in fear from near-humans, whether that meant a sick or dying (read: old) person or another form of life altogether. A collective fear of AI persists, driven by a host of primal drives and desires that operate beneath the subconscious. Hollywood will of course continue to capitalize on these fears. Before we start monster-fying our new AI overlords, we would do well to remember that today’s robots began as human dreams, the dreams of apes that evolved past the point of too smart for their own good. As Asimov’s laws indicate, if we want to stay on top of the machines, we will need to call upon everything that helped us build them in the first place.