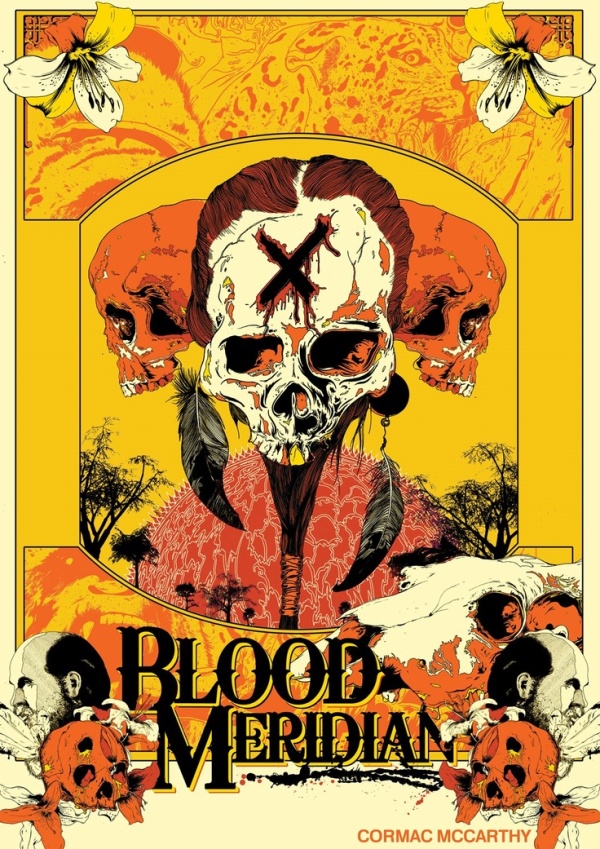

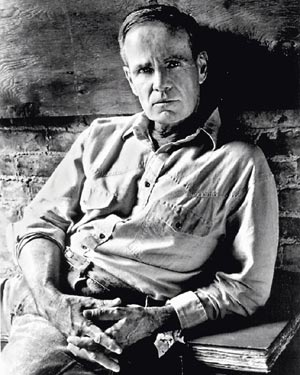

BY LUKE ROBERT HOPELY Cormac McCarthy writes spectral Western epics that both examine and embody (and, some would say, revel in) the savage beauty of man’s inhumanity to man. There are many Cormac McCarthy books you should read before you die, but if you only read one, make it Blood Meridian. This book does two things, and it does them with the same pitiless efficacy that makes his prose crackle. First, it gets its point across, and that point is how goddamn awful humans are, how we lust lust for violence, how we always have and always will. McCarthy underscores that last point by prefacing the book with an excerpt from an anthropological paper reporting that a 300,000 year old skull found in Ethiopia had been scalped. In other words, humans have been slaughtering each other for at least 300 millennia — that’s a long history of malevolence. Secondly, this book is jaw-droppingly beautiful. Even though Blood Meridian traffics in unspeakable violence set in impossibly bleak landscapes, you will find yourself turning each page giddy with anticipation of what gorgeously rendered bloodbath lurks on the next page. As such, McCarthy proves his point: mankind is inescapably drawn to the pornography of transcendental violence.

BY LUKE ROBERT HOPELY Cormac McCarthy writes spectral Western epics that both examine and embody (and, some would say, revel in) the savage beauty of man’s inhumanity to man. There are many Cormac McCarthy books you should read before you die, but if you only read one, make it Blood Meridian. This book does two things, and it does them with the same pitiless efficacy that makes his prose crackle. First, it gets its point across, and that point is how goddamn awful humans are, how we lust lust for violence, how we always have and always will. McCarthy underscores that last point by prefacing the book with an excerpt from an anthropological paper reporting that a 300,000 year old skull found in Ethiopia had been scalped. In other words, humans have been slaughtering each other for at least 300 millennia — that’s a long history of malevolence. Secondly, this book is jaw-droppingly beautiful. Even though Blood Meridian traffics in unspeakable violence set in impossibly bleak landscapes, you will find yourself turning each page giddy with anticipation of what gorgeously rendered bloodbath lurks on the next page. As such, McCarthy proves his point: mankind is inescapably drawn to the pornography of transcendental violence.

The first line of the novel is a command reminiscent of the epic introduction of Moby Dick, but instead of “Call me Ishmael” McCarthy urges us to “See the child.” In just a few pages this unnamed child grows into the unnamed kid who is the protagonist of the story, a cold-blooded killer who can “neither read nor write and in him broods already a taste for mindless violence.” This is about as much backstory we learn about The Kid. McCarthy has never been big on back story, preferring instead to define characters by their actions in the present. By the age of 15, The Kid is already a shady drifter with a history of violence. After killing a bartender in Texas with a beer bottle after a financial dispute, he beats feet and winds up joining a hapless band of Army irregulars looking to start shit with Mexico. These guys are totally unprepared for the arid deprivations of the desert and would have surely died of thirst even if they had somehow eluded massacre by a raging horde of blood-crazed Comanches (who sodomize their prisoners before decapitating them) in one of the most terrifying and unforgettable passages of the book.

Somehow The Kid survives the onslaught and the real story begins when he joins forces with a historically-factual group of cowboy scalp  hunters in search of Apache skull top trophies. They come to the city of Chihuahua half-drunk, accessorized with human ears and teeth, riding wild-eyed ponies on saddles made of human skin, and carrying “bowie knives the size of claymores and short two-barreled rifles with bores you could stick your thumb in.” McCarthy’s overarching vision of human savagery — from bloodthirsty Mongol horseman to rapacious Viking raiders — is embodied in this posse of psychopathic cowboys slaughtering Indians. The trail leads them across the border into the darkest reaches of Mexico where there will be a terrible day of reckoning.

hunters in search of Apache skull top trophies. They come to the city of Chihuahua half-drunk, accessorized with human ears and teeth, riding wild-eyed ponies on saddles made of human skin, and carrying “bowie knives the size of claymores and short two-barreled rifles with bores you could stick your thumb in.” McCarthy’s overarching vision of human savagery — from bloodthirsty Mongol horseman to rapacious Viking raiders — is embodied in this posse of psychopathic cowboys slaughtering Indians. The trail leads them across the border into the darkest reaches of Mexico where there will be a terrible day of reckoning.

McCarthy’s remarkable facility with language transforms the familiar Western desertscapes of the Lone Ranger and Tonto into blood-soaked wastelands of sun-dried carnage — and it’s just so beautiful. Even the adepts of photoshopping can’t hold a candle to McCarthy’s majestic, mystical depictions of the Mexican desert. He writes like a man well-acquainted with the cactoidal tang of peyote, but I suspect his true genius lies in the fact that he never needed psychedelics to get there. McCarthy doesn’t just say “the sun rose,” instead he writes:

The sun in the east flushed pale streaks of light and then a deeper run of color like blood seeping up in sudden reaches flaring planewise and where the earth drained up into the sky at the edge of creation the top of the sun rose out of nothing.

Instead of “there was a thunderstorm,” he writes:

All night sheet lightning quaked sourceless to the west beyond the midnight thunderheads, making a bluish day of the distant desert, the mountains on the sudden skyline stark and black and livid like a land of some other order out there whose true geology was not stone but fear.

His sentences run on and on as if trying to outrun the vultures of his own mortality, as the landscape speeds by in a hallucinatory blur of half-recognizable images, like the “crumpled butcher paper mountains” or the “lone albino ridge, sand or gypsum, like the back of some pale sea beast.” All you can do is sit back and just say, “wow.” This kind of feverish kaleidoscopic writing is also used to render the jarring violence in the book with ultra-vivid detail. When the capillaries in the eyes of a man being scalped begin to break up, McCarthy writes that “in those dark pools there sat each a small and perfect sun.” The horror. The horror. But even more frightening than all the poetic slaughter and suffering is the character of The Judge: Huge, hairless, albino, and sadism incarnate, who knows everything and spares no one and says things like “moral law is the disenfranchisement of the powerful in favor of the weak” and “everything that exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.” I think he is one of the most interesting characters in all of literature, and, as I read this book his philosophy I couldn’t help but see his point. There are no plot surprises in this book, all the notable events that will occur are listed at the beginning of the chapters, like some epic poem of impending doom. Reading Blood Meridian is to look into the abyss, a staring contest you were born to lose.