Artwork by TOMMASO PINCIO

If David Foster Wallace were alive today, would the famously introverted author be flattered to see himself on the big screen, or horrified at the commodification of his very identity? James Ponsoldt’s new film The End of the Tour recreates five days that the late author David Foster Wallace spent traveling around the Midwest with Rolling Stone Magazine writer David Lipsky around 1996, shortly after Wallace’s critically acclaimed novel Infinite Jest was published. In the film, the two men have a number of philosophical conversations about writing, life, sex, and fame — kind of like if My Dinner With Andre was set inside a rental car instead of at a restaurant table. The film was produced by A24 and DirecTV, and it recently premiered at the Sundance Film  Festival where it received mostly favorable reviews. There has been much discussion about the casting choices of Jason Segel as Wallace and Jesse Eisenberg as David Lipsky. The knock on Segel, who is best known for his roles in baudy, populist comedies, is that he’s just not a serious enough actor to play the highly intellectual Wallace. Similar doubts were expressed about Eisenberg playing Lipsky. However, critics who’ve seen the film report that the actors’ portrayals are respectful and authentic, and in interviews Segel has demonstrated a solid grasp of Wallace’s work.There has been some controversy surrounding the film, since both Wallace’s former editor and his family say that that Wallace would have never signed off on the project. Meanwhile, director James Ponsoldt and writer Donald Margulies have said that they hope the film will lead the uninitiated to Wallace’s work. It seems The End of the Tour has indeed sparked new discussions about Infinite Jest as well as his other works. The filmmakers stress, however, that they are merely focusing on Lipsky’s five days spent touring with Wallace and that the film is far from a comprehensive look at his life and work. The End Of The Tour will be released some time in 2015, although an exact release date was yet to be determined as of press time. — EMMA BAILEY

Festival where it received mostly favorable reviews. There has been much discussion about the casting choices of Jason Segel as Wallace and Jesse Eisenberg as David Lipsky. The knock on Segel, who is best known for his roles in baudy, populist comedies, is that he’s just not a serious enough actor to play the highly intellectual Wallace. Similar doubts were expressed about Eisenberg playing Lipsky. However, critics who’ve seen the film report that the actors’ portrayals are respectful and authentic, and in interviews Segel has demonstrated a solid grasp of Wallace’s work.There has been some controversy surrounding the film, since both Wallace’s former editor and his family say that that Wallace would have never signed off on the project. Meanwhile, director James Ponsoldt and writer Donald Margulies have said that they hope the film will lead the uninitiated to Wallace’s work. It seems The End of the Tour has indeed sparked new discussions about Infinite Jest as well as his other works. The filmmakers stress, however, that they are merely focusing on Lipsky’s five days spent touring with Wallace and that the film is far from a comprehensive look at his life and work. The End Of The Tour will be released some time in 2015, although an exact release date was yet to be determined as of press time. — EMMA BAILEY

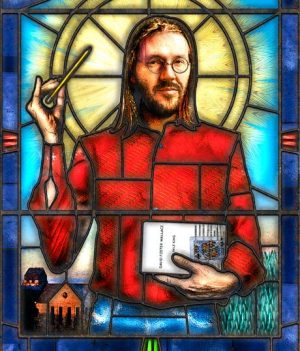

ESQUIRE: The last work of fiction by the greatest American writer of my generation is an incomplete and weirdly fractured pseudo memoir about the United States tax code and several employees of the Internal Revenue Service. The work is frustratingly difficult in places. It’s potholed throughout by narrative false starts and dead ends. Characters  appear without introduction and disappear without cause. I often found myself putting the novel down, and I didn’t always want to pick it up again. Then I did. Because The Pale King, an unfinished manuscript that will be published this month by Little, Brown, is one of the saddest and most lovely books I’ve ever read. This sadness, of course, has something (or probably a lot) to do with David Foster Wallace’s suicide by hanging in 2008. With lots of exceptions, killing yourself is a bad idea. It’s a particularly bad idea for writers. First, you run the risk of turning all your prior efforts into one long suicide note. What’s worse, especially if you’re a writer as beloved as Wallace, is that you may be turned into some kind of icon. And, as D.F.W. himself once wrote, “to make someone an icon is to make him an abstraction, and abstractions are incapable of vital communication with living people.” MORE

appear without introduction and disappear without cause. I often found myself putting the novel down, and I didn’t always want to pick it up again. Then I did. Because The Pale King, an unfinished manuscript that will be published this month by Little, Brown, is one of the saddest and most lovely books I’ve ever read. This sadness, of course, has something (or probably a lot) to do with David Foster Wallace’s suicide by hanging in 2008. With lots of exceptions, killing yourself is a bad idea. It’s a particularly bad idea for writers. First, you run the risk of turning all your prior efforts into one long suicide note. What’s worse, especially if you’re a writer as beloved as Wallace, is that you may be turned into some kind of icon. And, as D.F.W. himself once wrote, “to make someone an icon is to make him an abstraction, and abstractions are incapable of vital communication with living people.” MORE

NEWSWEEK: Since the arrival of The Pale King, Wallace’s estate and Pietsch have published several books: This Is Water, the philosophical and quietly rousing commencement address Wallace gave at Kenyon College in 2005; Signifying Rappers, the superannuated but amusing pop-culture treatise he wrote about hip-hop with his college friend Mark Costello; Both Flesh and Not, a collection of lesser-known essays; Fate, Time, and Language: An Essay on Free Will, a discussion of the philosopher Richard Taylor written when Wallace was in college, where he studied literature and philosophy

Now comes The David Foster Wallace Reader, a big and handsome tome with selections from both his fiction and nonfiction, as well as a smattering of teaching materials that include discussions with his mother about the finer points of English grammar (e.g., the pesky lie/lay dichotomy). Its selections were chosen by 24 editorial advisers, but the project unquestionably belongs to Pietsch. Now the chief of the Hachette publishing behemoth, he seems to approach the posthumous publication of Wallace’s work with the zeal of a missionary looking over a sea of heathens. Wallace’s death was an abomination he could not prevent, but he will not allow the man’s work to pass into oblivion. But do we need The David Foster Wallace Reader? According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, probably not. Though the book seems like a Christmas gift in the making, it contains almost no new work. But I think I get what Pietsch is doing here, and I am all for it. You need evidence of miracles for sainthood; you need something only marginally more mundane to sustain a bid for lasting literary greatness, for entrance into that pantheon protected from the vicissitudes of literary taste. This is part of that effort, a reminder of how good Wallace could be, whether he was writing about Kafka or the Illinois State Fair, whether he was making stuff up or trying to see things as they actually are.

finer points of English grammar (e.g., the pesky lie/lay dichotomy). Its selections were chosen by 24 editorial advisers, but the project unquestionably belongs to Pietsch. Now the chief of the Hachette publishing behemoth, he seems to approach the posthumous publication of Wallace’s work with the zeal of a missionary looking over a sea of heathens. Wallace’s death was an abomination he could not prevent, but he will not allow the man’s work to pass into oblivion. But do we need The David Foster Wallace Reader? According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, probably not. Though the book seems like a Christmas gift in the making, it contains almost no new work. But I think I get what Pietsch is doing here, and I am all for it. You need evidence of miracles for sainthood; you need something only marginally more mundane to sustain a bid for lasting literary greatness, for entrance into that pantheon protected from the vicissitudes of literary taste. This is part of that effort, a reminder of how good Wallace could be, whether he was writing about Kafka or the Illinois State Fair, whether he was making stuff up or trying to see things as they actually are.

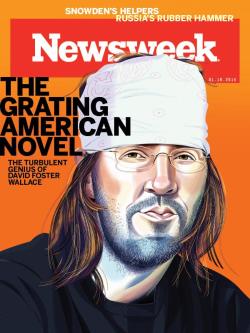

I don’t mean that his writing is flawless. In fact, the flaws are all too obvious: a charming loquacity that could lapse into annoying logorrhea, an inability to fashion anything resembling plot, and, most damning, the inability to resolve the question of irony, namely whether it was a useful strategy or a dangerous disguise. Some were simply “allergic” to his style, which in both the fiction and nonfiction scrambled technical jargon with mall-escalator colloquialisms. The novelist Richard Ford once told me that he tried reading Infinite Jest but saw no point in continuing after a while: “OK, that’s enough,” he remembered thinking as he closed the book. But those who love Wallace overlook those faults. His voice seems geared to the overeducated American college graduate plodding toward adulthood, tired of sarcasm but resorting to it too often, suspicious of belief but desperate for faith, awash in meanings but lacking Meaning. He is the slightly older, vastly smarter friend who’d break it all down over a joint; I don’t think his ever-present bandanna and stubble, which lent him the aura of a New Age guru, were accidental vestments. MORE

PODCAST: David Foster Wallace At The Philadelphia Free Library, 2004

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following was written in the wake of David Foster Wallace’s suicide in 2008

BY JEFF DEENEY When David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest was released I was an undergrad at the University of Chicago and living in the kind of cavernous and dumpy five bedroom basement apartment that only an impoverished student could love. I remember being sold on the book after reviews compared it to the Naked Lunch. I read the first chapter and immediately started nagging people around me, demanding that they get a copy. It was clear that this wasn’t just another new book. This was a major new book, a literary event. Everyone needed to read this.

BY JEFF DEENEY When David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest was released I was an undergrad at the University of Chicago and living in the kind of cavernous and dumpy five bedroom basement apartment that only an impoverished student could love. I remember being sold on the book after reviews compared it to the Naked Lunch. I read the first chapter and immediately started nagging people around me, demanding that they get a copy. It was clear that this wasn’t just another new book. This was a major new book, a literary event. Everyone needed to read this.

U of Chicago is known as a wonky school full of nerdy intellectual types so it wasn’t surprising that I was able to easily gather a group willing to pick up this 1079 page cinderblock of a book. My girlfriend at the time was child prodigy-smart and had been writing essays about the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein since high school. I attempted to read Wittgenstein in college but all I got out of it was a headache and the dismal suspicion I was not nearly as smart as I thought I was. Foster Wallace was big on Wittgenstein and incorporated the philosopher’s extraordinarily complicated logic into his writing, so it was good to have an expert on board.

My roommates got sucked into the book next and we all brought our various areas of relevant knowledge – math, psychology, film – to bear on the text. We spent endless afternoons in that dark and dank basement cave with our copies in our laps, trying to decipher the book’s many riddles. We were consumed with Foster Wallace’s ideas and frantically argued our interpretations of many notoriously ambiguous passages. It was an exhilarating experience, exactly what college is supposed to be.

The book also resonated with me on a personal level. Don Gately, the affable but dimwitted working class drug addict at the heart of one of the novel’s three major story lines was a carbon copy of every burnout dude I grew up with in Delaware County. At 22  I had already been to rehab and had personal experience with the addiction recovery culture that Foster Wallace clearly admired and placed at the center of his novel. The book was important to me not only because it was a major literary effort by a young novelist, but also because the author was saying that these things I experienced, that defined who I was, were important for defining our times.

I had already been to rehab and had personal experience with the addiction recovery culture that Foster Wallace clearly admired and placed at the center of his novel. The book was important to me not only because it was a major literary effort by a young novelist, but also because the author was saying that these things I experienced, that defined who I was, were important for defining our times.

For months after reading Infinite Jest our love affair with it continued; there were constant references made to various characters and scenes during casual conversations in my circle of friends. Then, just as the Infinite Jest afterglow was fading out, Foster Wallace released his next book, A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. It was a compilation of essays introducing his quirky and occasionally exasperating nonfiction style. Many of the essays were outrageously funny, and the book also came loaded with another exhaustive set of footnotes (there were 100 pages of them for Infinite Jest). Some readers still loved Foster Wallace’s idiosyncracies, such as his insistence on footnoting, but others like me were starting to find them seriously tedious.

The most important essay in A Supposedly Fun Thing, and possibly of Foster Wallace’s career, was “E Unibus Pluram,” a critique of television’s impact on fiction writing and the tyranny of irony among contemporary young writers. His central message was that irony, while often devilishly satisfying, is cheap and easy. Sincerity and serious artistic statements are increasingly difficult for young writers to pull off because they leave the writer open to mockery by his trendsetting, hipster peers. Caring isn’t cool, and risking looking uncool is a cardinal sin for young writers.

Foster Wallace’s argument about irony is probably more important with the advent of blogs than it was when he wrote it. Now there are bloggers whose writing exists solely to sarcastically deride the work of other writers. Wallace knew that snark, as it has since come to be known, is a brain-dead proposition that serves no function but to satisfy the author’s own smugness and assure readers of their own hipness for being in on the joke. Unfortunately, this fundamentally toxic reliance on irony and mockery continue to define much of blog culture; hopefully as the medium matures more writers will grow out of it.

There are disagreements in opinion about the arc of Foster Wallace’s career in the post-Infinite Jest era. My own opinion is that he began to crash and burn after A Supposedly Fun Thing. His writing became increasingly, intentionally more dense, and it was pretty damn dense to start with. He stopped crafting engaging and funny protagonists and started to dwell on narcissistic types who were drowning in their self-absorption. Foster Wallace’s own self-absorption was starting to suffocate me as a reader; I wished a gutsy editor would finally handcuff him on the footnote thing, which in my opinion reached farcical proportions in his last couple books. I saw him speak at the Free Library in 2004 and remember being left ice cold by his reading. By this point his characters didn’t even have names; they were faceless sketches, vehicles for abstract logic games whose point, it seemed, was to confirm Foster Wallace’s own encroaching solipsism.

There are disagreements in opinion about the arc of Foster Wallace’s career in the post-Infinite Jest era. My own opinion is that he began to crash and burn after A Supposedly Fun Thing. His writing became increasingly, intentionally more dense, and it was pretty damn dense to start with. He stopped crafting engaging and funny protagonists and started to dwell on narcissistic types who were drowning in their self-absorption. Foster Wallace’s own self-absorption was starting to suffocate me as a reader; I wished a gutsy editor would finally handcuff him on the footnote thing, which in my opinion reached farcical proportions in his last couple books. I saw him speak at the Free Library in 2004 and remember being left ice cold by his reading. By this point his characters didn’t even have names; they were faceless sketches, vehicles for abstract logic games whose point, it seemed, was to confirm Foster Wallace’s own encroaching solipsism.

There will be a lot written in years to come about this shift towards darkness and increasingly diffuse abstraction in Foster Wallace’s later writing. Already on blogs some are positing that Wallace was sending messages about his own internal struggles through such characters as “The Depressed Person.” The hunt is on for other potentially illuminating passages in his works about various psychopathologies and metaphysical proclamations that might help explain his seemingly inexplicable decision to end his own life.

What is most unfortunate about Foster Wallace’s death, as is the case for all great artists whose lives end prematurely, is that we’ll never know what he would have said about things to come. He saw our increasingly bizarre and fractured culture with such tremendous clarity, and nailed his often complicated but spot-on conclusions about our world with an Olympian elan. He will be dearly missed.

UPROXX: Since his death in 2008, DFW moments and references have found their way into pop culture, and with each reference in TV and film, a DFW fan swoons with delight. I spoke with DT Max, who wrote the biography of Wallace Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, and he noted, “It’s interesting to see David percolating culture in this way. It’s not really surprising. A lot of creative people, including people in film and TV, were into him.” Max speculates that the references may have made Wallace uncomfortable and said, “[Wallace] had mixed feelings about the level of fame he had. And I think he would have ignored it… he was always afraid he would be seduced by these things so he went out of his way to stay away from them.” It’s interesting, too, considering Wallace was addicted to television. As Max wrote in his Wallace bio, “Wallace hardly had a normal relationship with television, let alone his life,” and that TV was his “drug of last resort.” And In Wallace’s essay on television, “E Univus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction” (The Review of Contemporary Fiction, 1993) he wrote: “Television, from the surface on down, is about desire. Fictionally speaking, desire is the sugar in human food.” While his novel Infinite Jest examined entertainment’s toll on society, his later novel, The Pale King, explored boredom. “I think he certainly would have argued, towards the end of his life, that people are afraid of the sounds of their own mind,” Max said, “So television is one way to blot out the sound of their own minds. And that boredom, or mindfulness — which is a type of boredom, sometimes was an attempt on his part to really listen to the sound of his mind.” And so with that in mind, here are some favorite DFW moments from TV, film, and music: MORE

RELATED: In The Decemberists’ music video for “Calamity Song” (directed by Mike Schur) the Enfield Tennis Academy tennis match at Eschaton, a famous scene from Infinite Jest, is recreated. Decemberist frontman Colin Meloy had just finished the book when he wrote the song, which inspired the lyrics and, in turn, the video. MORE