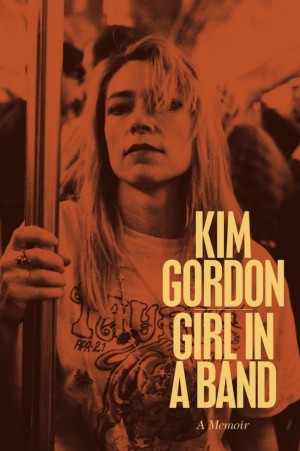

THE STRANGER: The mood of the crowd at the Neptune last night for Kim Gordon‘s conversation with Bruce Pavitt about her book Girl In A Band ranged from slightly confused to completely livid. No one, as far as I could tell, left feeling satisfied. I interviewed folks as they came out, asking them simply what they thought of the night. All their quotes are at the end. But what happened? Many people blamed Pavitt for talking too much about the past—the early Sub Pop days (Sonic Youth’s contribution to the first Sub Pop compilation is how they met and know each other), inviting her to dish on Courtney Love, reminiscing about the time Sonic Youth invited Mudhoney to tour Europe with them, and riffing on Gordon’s early-’90s clothing line X Girl. It did feel very casual and unstructured, two people just sort of chatting a little awkwardly about  the good old days, neither one of them exactly jumping into the topic of the book. Other people were disappointed by the audience questions, which, save for maybe three of them, either made no sense or clumsily pushed her to talk about feminism. Though it was a bit hard to hear, I swear someone asked: “So, what’s it like being a woman in a band?” Then someone asked: “Do you spell Riot Grrl with two Rs or three?” Gordon’s response: “That’s not really my area of expertise. I’m, um, a bad speller.”

the good old days, neither one of them exactly jumping into the topic of the book. Other people were disappointed by the audience questions, which, save for maybe three of them, either made no sense or clumsily pushed her to talk about feminism. Though it was a bit hard to hear, I swear someone asked: “So, what’s it like being a woman in a band?” Then someone asked: “Do you spell Riot Grrl with two Rs or three?” Gordon’s response: “That’s not really my area of expertise. I’m, um, a bad speller.”

The very best question, in my opinion, was from our own Kelly O, who asked: “In Vanity Fair, you said that you listened to a lot of hiphop during your breakup. Was there one particular record or artist who helped you the most?” Kim responded that she had mainly listened to mixes from friends, but that there was “a lot of Nas on there.” I’ll try not to dwell on this all day, as I could easily word-barf on art, women, music, books, and expectations for the next four hours and rest of my life, but there’s one last element in all this muddlement that we haven’t talked about much—Kim Gordon herself. As with any art form, writing a good book does not necessarily mean you will be able to talk about it well, or even want to talk about it at length, no matter how the commercial book-selling cycle is supposed to work (“Except for this book [laughs], I don’t really know how to do anything commercial or conventional,” Gordon said at one point). Gordon was and is the eternally cool cucumber, but she too could have steered the interview had she wanted to. If you don’t like a question or the direction of a conversation, take it somewhere else. Take the mic and talk about what you want to talk about. But honestly, it seemed like she wasn’t in the mood to talk too much, not in an uptight way, maybe more in a stoned way (also very cool). And let’s be real, it’s Kim Fucking Gordon—does she really need Pavitt or anyone in the audience to help her talk about her book? I can’t imagine she was just sitting there, waiting for someone to ask the right question so she could jump up and launch into the feminist rant we were all secretly hoping for. MORE

NEW YORK MAGAZINE: Of course, the hopes people took from this couple weren’t about love per se. (We are more than used to watching public figures fall in and out of love; it’s a national sport.) They were bigger and more specific than that, oversize versions of the same aspirations invested in couples (and ex-couples) from long-running bands like Yo La Tengo and Superchunk—hopes that revolve around what you might call “life opportunities.” In Gordon and Moore, you could imagine empirical proof that a lot of things you feared were true about life—things your parents always warned you about—did not necessarily have to be that way. For instance: that a career in an avant-garde rock band might lead not into penury, instability, and isolation but instead to a place in a perma-cool family living in a nice house in the Berkshires. That committing to being a feminist, punk, or  artist would not cut you off from normal people and force you into huge compromises in your domestic affairs but might actually lead you to someone who’d share all of those commitments. That a heterosexual married couple could not only work together but collaborate as equals and throw equally large shadows. What better fairy tale to reassure young people that they don’t ever have to settle? It’s like getting a notarized letter containing three important promises: that your bohemian dreams won’t conflict with middle-class contentment; that maybe the reason your parents’ generation all divorced was that they never found partners cool enough to be in a band with; and that you, as an adult, could do better. MORE

artist would not cut you off from normal people and force you into huge compromises in your domestic affairs but might actually lead you to someone who’d share all of those commitments. That a heterosexual married couple could not only work together but collaborate as equals and throw equally large shadows. What better fairy tale to reassure young people that they don’t ever have to settle? It’s like getting a notarized letter containing three important promises: that your bohemian dreams won’t conflict with middle-class contentment; that maybe the reason your parents’ generation all divorced was that they never found partners cool enough to be in a band with; and that you, as an adult, could do better. MORE