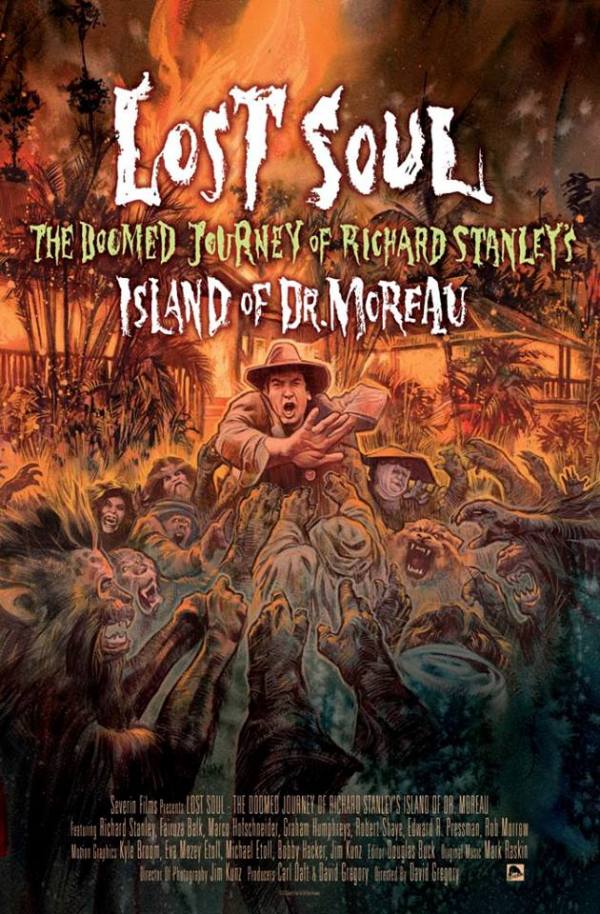

LOST SOUL: THE DOOMED JOURNEY OF RICHARD STANLEY’S ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU (2014, directed by David Gregory, 97 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Shot like an expansive DVD extra, director David (Plague Town) Gregory’s unassuming documentary Lost Souls: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau overcomes its generic visual style by having a whopper of a tale to tell. Stanley was a South African-born director who made a pair of stylish low budget genre films (1990’s Hardware and 1992’s Dust Devil) that made him a favorite of the Fangoria crowd. Before procuring the novel’s rights, Stanley wrote an ambitious screenplay adaptation of H.G. Wells’ vivisection classic The Island of Dr. Moreau that spun off from the novel with all sorts of ghoulish bestial developments. It took the then-building prestige of New Line Films to wrangle the film rights and before you know it Stanley’s modestly budgeted sci-fi horror film has ballooned into a major Hollywood production with the temperamentally unpredictable duo of Marlon Brando and Val Kilmer on board.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Shot like an expansive DVD extra, director David (Plague Town) Gregory’s unassuming documentary Lost Souls: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau overcomes its generic visual style by having a whopper of a tale to tell. Stanley was a South African-born director who made a pair of stylish low budget genre films (1990’s Hardware and 1992’s Dust Devil) that made him a favorite of the Fangoria crowd. Before procuring the novel’s rights, Stanley wrote an ambitious screenplay adaptation of H.G. Wells’ vivisection classic The Island of Dr. Moreau that spun off from the novel with all sorts of ghoulish bestial developments. It took the then-building prestige of New Line Films to wrangle the film rights and before you know it Stanley’s modestly budgeted sci-fi horror film has ballooned into a major Hollywood production with the temperamentally unpredictable duo of Marlon Brando and Val Kilmer on board.

What could go wrong? Everything, and terribly. Without overstating things, Gregory paints a picture of a reality that begins to resemble the perverse action of the Wells’ book. For starters, a supernatural spell is cast. Stanley arrives on location in Australia with one white linen suit he plans to wear for the whole shoot like he is Dr. Moreau. He has his supporters but a group of doubters in the production have him removed from his film early in the shoot, to be replaced by the crusty old school director John Frankenheimer, who is best known for directing The Manchurian Candidate and Seconds. Stanley disappears into the jungle only to later make an unbelievable return. Brando arrives late, still mourning the suicide of his young daughter, and suddenly he is the new mad scientist on the set. As production breaks down, the costumed extras — drawn from a community of crusty Australian hippies — descend into Bacchanalia worthy of their half-man/half-beast roles.

Gregory allows many people in the production to have their say, from co-star Fairuza Balk (who paints a jet-black picture of Hollywood politics) to the extras and lowly gofers, who were bemused, well-paid spectators of the madness. (Oddly unmentioned: David Thewlis of Mike Leigh’s Naked, who had a major role in the film) These sometimes conflicting perspectives give the story the air of legend. The Island of Dr. Moreau finally came out in 1996 and the best parts have an unhinged quality that was emphasized in Stanley’s original vision. Stanley’s career never recovered, Brando is dead and Val Kilmer has gone from top tier star to bloated B-movie gossip fodder — a fate richly deserved if you believe the nasty portrait of him painted here. While destiny has humbled them all, Lost Souls has given these fascinating men a chance to loom large again, both on the PhilaMOCA screen and in the annals of cinematic disasters.