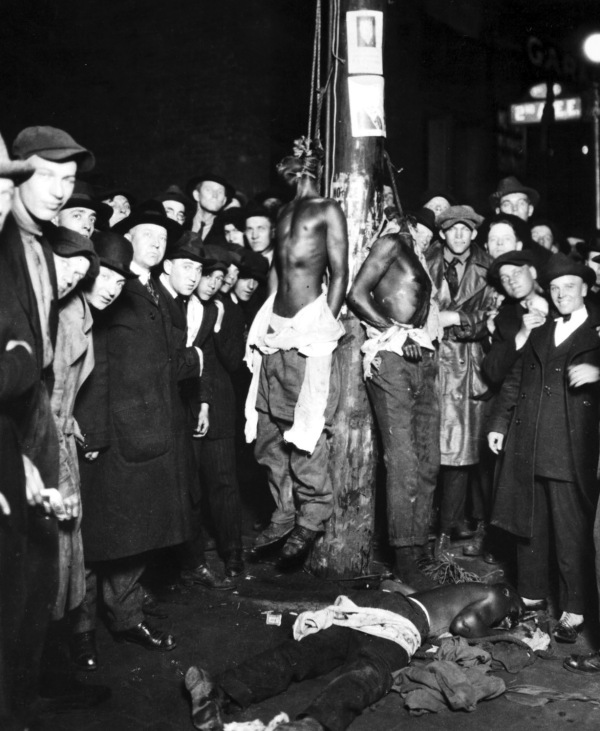

ABOVE: In Duluth, Minnesota, on June 15, 1920, three young African-American traveling circus workers were lynched after having been accused of having raped a white woman and jailed pending a grand jury hearing. This image was sold as a souvenir postcard. A physician’s subsequent examination of the woman found no evidence of rape or assault. The alleged “motive” and action by a mob were consistent with the “community policing” model. The book, The Lynchings in Duluth (2000) by Michael Fedo has documented the events.[36]

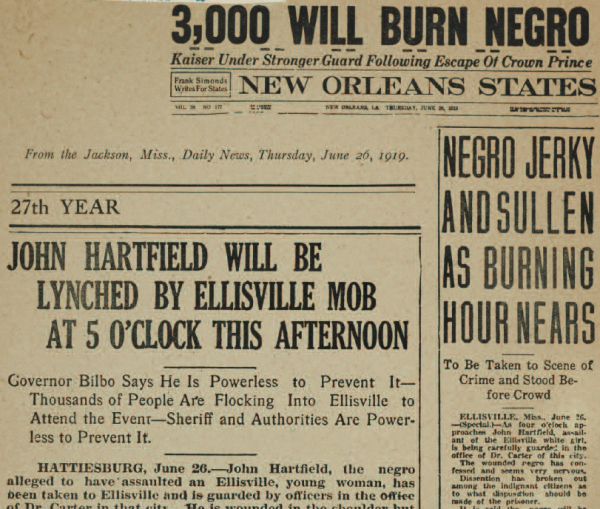

NEW YORK TIMES: It is important to remember that the hangings, burnings and dismemberments of black American men, women and children that were relatively common in this country between the Civil War and World War II were often public events. They were sometimes advertised in newspapers and drew hundreds and even thousands of white spectators, including elected officials and leading citizens who were so swept up in the carnivals of death that they posed with their children for keepsake photographs within arm’s length of mutilated black corpses. These episodes of horrific, communitywide violence have been erased from civic memory in lynching-belt states like Louisiana, Georgia, Alabama, Florida and Mississippi. MORE

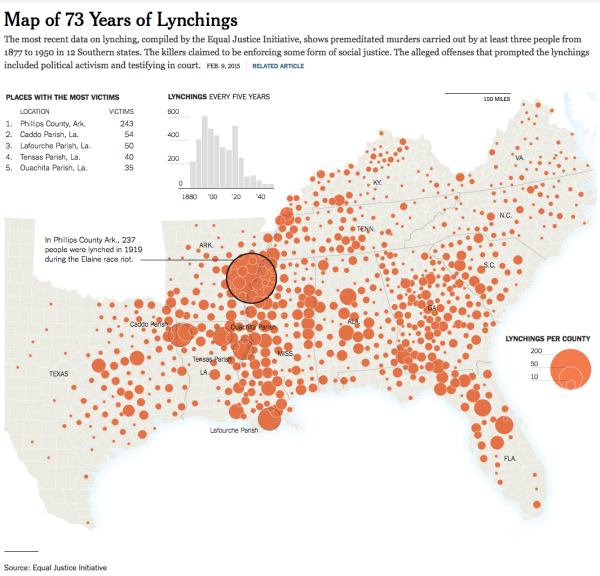

REUTERS: Lynchings in which mobs raided jailhouses to hang, torture and burn alive black men, sometimes leading to public executions in courthouse squares, occurred  more often in the U.S. South than was previously known, according to a report released on Tuesday. The slightest transgression could spur violence, the Equal Justice Initiative found, as it documented 3,959 victims of lynching in a dozen Southern states. The group said it found 700 more lynchings of black people in the region than had been previously reported. The research took five years and covered 1877 to 1950, the period from the end of post-Civil War Reconstruction to the years immediately following World War Two. The report cited a 1940 incident in which Jesse Thornton was lynched in Alabama for not saying “Mister” as he talked to a white police officer. In 1916, men lynched Jeff Brown for accidentally bumping into a white girl as he ran to catch a train, the report said. MORE

more often in the U.S. South than was previously known, according to a report released on Tuesday. The slightest transgression could spur violence, the Equal Justice Initiative found, as it documented 3,959 victims of lynching in a dozen Southern states. The group said it found 700 more lynchings of black people in the region than had been previously reported. The research took five years and covered 1877 to 1950, the period from the end of post-Civil War Reconstruction to the years immediately following World War Two. The report cited a 1940 incident in which Jesse Thornton was lynched in Alabama for not saying “Mister” as he talked to a white police officer. In 1916, men lynched Jeff Brown for accidentally bumping into a white girl as he ran to catch a train, the report said. MORE

BUZZFEED: In one such spectacle lynching, in 1904 in Doddsville, Mississippi, the victims were a black man named Luther Holbert, who allegedly killed a white landowner, and a black woman believed to be his wife. They were tied to a tree and forced to hold out their hands as their fingers were “methodically chopped off” and distributed to the gathered crowd as “souvenirs,” the report said. Their ears were cut off, and their attackers used a corkscrew to “bore holes” into their bodies and “pull out large chunks of ‘quivering flesh.'” The report said both were then thrown into a fire and burned. “The white men, women, and children present watched the horrific murders while enjoying deviled eggs, lemonade and whiskey in a picnic-like atmosphere,” the report said. MORE

NIEMAN REPORTS: On December 4, 1931, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, an African American named Matthew Williams shot and killed his white employer, then turned a pistol on himself, inflicting a wound. Staggering away from the scene of the crime, he was shot by the employer’s son, then arrested and taken to a Salisbury hospital. Hours later, a mob descended on the building, seized Williams, dropped him from a window, dragged him to the courthouse green, and hung him from a tree. A crowd of 2,000 men, women and children cheered. The body was then doused with gasoline and burned. One member of the mob cut off several of Williams’s toes and carried them off as souvenirs. It was the first lynching the state had witnessed in 20 years. The local townspeople celebrated the occasion by draping the tree with an American flag. The 1931 lynching on the Eastern Shore revolted Mencken; he was furious that no one had done anything to stop Williams’s murder, only one of more than 5,000 lynchings that had occurred in the United States since 1922. MORE

TIME: There were lynchings in the Midwestern and Western states, mostly of Asians, Mexicans, and Native Americans. But it was in the South that lynching evolved into a semiofficial institution of racial terror against blacks. All across the former Confederacy, blacks who were suspected of crimes against whites—or even “offenses” no greater than failing to step aside for a white man’s car or protesting a lynching—were tortured, hanged and burned to death by the thousands. In a prefatory essay in Without Sanctuary, historian Leon F. Litwack writes that between 1882 and 1968, at least 4,742 African Americans were murdered that way. MORE

NPR: In most of the places where these lynchings took place — in fact in all of them — there was a functioning criminal justice system that was deemed “too good” for African-Americans. You had lynching of whites and others in the far West and in the early parts of the 19th century that would be called “frontier justice.” You did not have functioning justice system in, so people took things in their hands. Here we had very well established courts of laws, we had very well established criminal justice systems. Often these men were pulled from jails and pulled out of courthouses, where they could be lynched literally on the courthouse lawn. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: A block from the tourist-swarmed headquarters of the former Texas School Book Depository sits the old county courthouse, now a museum. In 1910, a group of men rushed into the courthouse, threw a rope around the neck of a black man accused of sexually assaulting a 3-year-old white girl, and threw the other end of the rope out a window. A mob outside yanked the man, Allen Brooks, to the ground and strung him up at a ceremonial arch a few blocks down Main Street. South of the city, past the Trinity River bottoms, a black man named W. R. Taylor was hanged by a mob in 1889. Farther south still is the community of Streetman, where 25-year-old George Gay was hanged from a tree and shot hundreds of times in 1922.And just beyond that is Kirvin, where three black men, two of them almost certainly innocent, were accused of killing a white woman and, under the gaze of hundreds of soda-drinking spectators, were castrated, stabbed, beaten, tied to a plow and set afire in the spring of 1922. The killing of Mr. Brooks is noted in the museum. The sites of the other killings, like those of nearly every lynching in the United States, are not marked. Bryan Stevenson believes this should change. On Tuesday, the organization he founded and runs, the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Ala., released a report on the history of lynchings in the United States, the result of five years of research and 160 visits to sites around the South. The authors of the report compiled an inventory of 3,959 victims of “racial terror lynchings” in 12 Southern states from 1877 to 1950. MORE

Click HERE to enlarge

NPR: There’s nothing marked in Montgomery [Ala.], or in most communities in the South, to this history of lynching, and we want to change that. … We want to erect markers and monuments at lynching sites all over this country. Because I think until we deal with this history, we talk about what it represents, we’re going to continue be haunted by this legacy of terrorism and violence that will manifest itself in ways that are problematic. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: The report argues compellingly that the threat of death by lynching was far more influential in shaping present-day racial reality than contemporary  Americans typically understand. It argues that The Great Migration from the South, in which millions of African-Americans moved North and West, was partly a forced migration in which black people fled the threat of murder at the hands of white mobs.

Americans typically understand. It argues that The Great Migration from the South, in which millions of African-Americans moved North and West, was partly a forced migration in which black people fled the threat of murder at the hands of white mobs.

It sees lynching as the precursor of modern-day racial bias in the criminal justice system. The researchers argue, for example, that lynching declined as a mechanism of social control as the Southern states shifted to a capital punishment strategy, in which blacks began more frequently to be executed after expedited trials. The legacy of lynching was apparent in that public executions were still being used to mollify mobs in the 1930s even after such executions were legally banned.

Despite playing a powerful role in the shaping of Southern society, the lynching era has practically disappeared from public discourse. As the report notes: “Most Southern terror lynching victims were killed on sites that remain unmarked and unrecognized. The Southern landscape is cluttered with plaques, statues and monuments that record, celebrate and lionize generations of American defenders of white supremacy, including public officials and private citizens who perpetrated violent crimes against black citizens during the era of racial terror.” MORE

DOWNLOAD: Lynching In America: Confronting A Legacy Of Racial Terror [PDF]

RELATED: The Hunting Of Billie Holiday

BILLIE HOLIDAY: Strange Fruit

TIME: “Strange Fruit” is a tragic song famously performed by Billie Holiday, one of America’s most tragic singers. The devastating image of “strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees” is the mournful heart of this antiracism song. Named song of the century by TIME in 1999, the lyrics were written by Abel Meeropol, an English teacher from the Bronx who in 1937 ran across a photograph of a lynching that both disturbed and inspired him. The resulting poem became the basis of the song two years later. Holiday’s live version of “Strange Fruit,” with only a piano backing her, is even more raw and heartfelt than the recording. You can feel her anguish, you can feel her sadness, you can feel her anger. It’s a song that is complicated in a unique way — such beautiful humanity in such a shameful topic. MORE