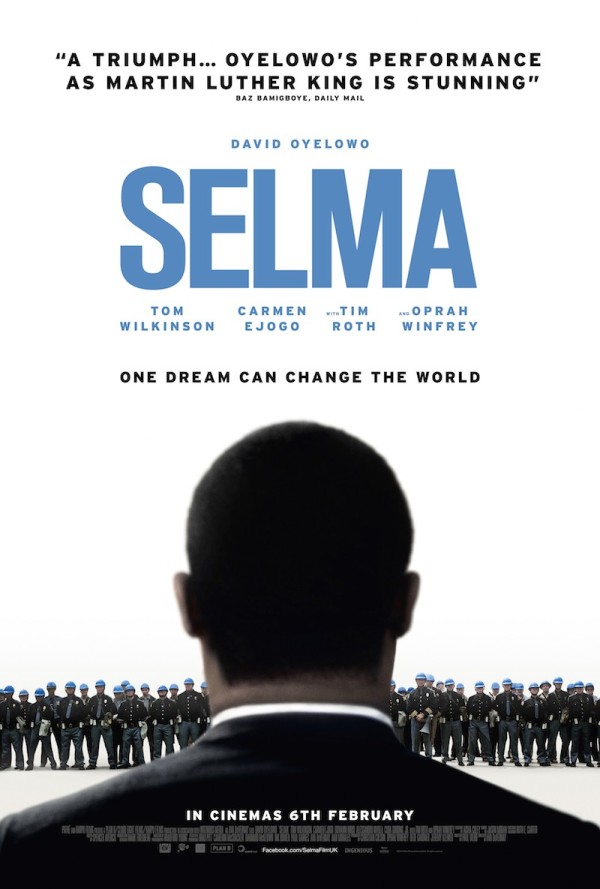

SELMA (2014, Directed by Ava DuVernay, 128 Minutes, U.S.)

![]() BY ZACHARY SHEVICH FILM CRITIC Selma opens with Martin Luther King Jr. practicing his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech in the mirror, anxiously second-guessing his choice of tie. It’s a rare departure to portray the revered leader of the civil rights movement as a complex, all-too-human being no more immune than the rest of us to life’s trivialities, rather than a messianic figure delivering his people from bondage — although, in fact, he was/is both.

BY ZACHARY SHEVICH FILM CRITIC Selma opens with Martin Luther King Jr. practicing his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech in the mirror, anxiously second-guessing his choice of tie. It’s a rare departure to portray the revered leader of the civil rights movement as a complex, all-too-human being no more immune than the rest of us to life’s trivialities, rather than a messianic figure delivering his people from bondage — although, in fact, he was/is both.

Director Ava Duvernay (I Will Follow, Middle of Nowhere) projects a nuanced perspective of the events surrounding the historic Selma-to-Montgomery civil rights marches. She captures the ambiance of the era with minimal flourishes, but the film still feels motivated by situation rather than a need to recreate history. Pomp and hagigraphy has killed lesser films overdetermined by the profound historical import of its subject, but Selma’s focused look into a single period of King’s life allows Duvernay to depict these events with the blood, sweat and tears of authenticity.

After King receives the Nobel in 1965, the movie jumps back in time to the 1963 Birmingham church bombing. Here, Duvernay’s altering of the timeline works to contextualize as well as dramatize MLK’s pursuit of the Voting Rights Act. It’s a slight change to history that sets the stage for the showdown in Selma, and one that evokes a thematic truth rather than a perfect chronological assembly of events. Given the film’s unapologetic application of creative license to history’s cause and effect, it’s hard to imagine why the criticisms of Lyndon B. Johnson’s portrayal have become such a large part of Selma’s off-screen narrative.

The film, originally conceived by screenwriter Paul Webb as a study of the tense relationship between Johnson and King, portrays Johnson as sympathetic to King’s cause while juggling the realpolitik responsibilities of power. “You’ve got one big issue, I’ve got 101,” Tom Wilkinson says, in that way Tom Wilkinson does all American voices, but with hints of gentle Southern twang. Selma returns repeatedly to the Oval Office showdowns that illustrate not only the high-stakes intensity of the moment but an indelible sense that the events set into motion a long ago will continue long after the film ends. In that sense, in the midst of an Oscars landscape featuring biopics that take far greater liberties with history, it’s hard to fathom why Selma has received such intensive scrutiny by the history police.

King is vividly channeled by David Oyelowo, who nails King’s speeches with a goosebump-inducing intensity, channeling the trembling cadences, roof-raising repetitions and whisper-to-a-scream dynamics of MLK’s been-to-the-mountaintop oratory. Duvernay’s King is similar to Spielberg’s Lincoln in that he serves as both provocateur and peacemaker, his wide, soulful eyes always deep-focused on the horizon of history in order to plot the way forward. As with Daniel Day Lewis’ Lincoln, Oyelowo makes us feel the full weight of the burden of history

that King shouldered.

In addition to Oyelowo, a roster of talented actors including Carmen Ejogo, Colman Domingo, Giovanni Ribisi, Stephan James and Wendell Pierce deliver captivating performances, often turning writerly lines into convincing dialog. Tim Roth channels George Wallace — the Mephistophelian governor of Alabama — with creepy aplomb, but the casting of Oprah Winfrey in the role of Annie Lee Cooper is the film’s greatest coup. Oprah is, above all things, the realization of Martin Luther King’s dream of a world where all God’s children are judged by the content of their character, not the color of their skin. If there was ever a question of where the audience’s sympathies lie, it is rendered moot the moment the fat, no-neck cracker police chief brings his truncheon down on Oprah’s skull with sickening force. As goes Oprah, so goes the nation. The rest is just history.