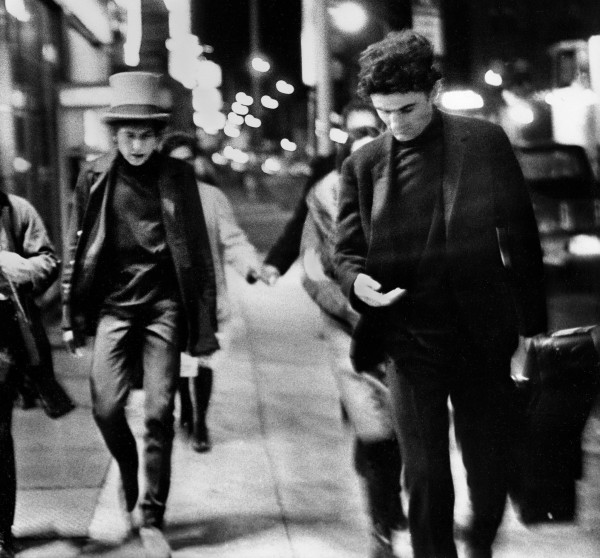

Bob Dylan & Victor Maymudes in Philadelphia 1964. Photo by DANIEL KRAMER/STALEY-WISE GALLERY

NEW YORK TIMES: The most vivid passages go back further — to 1964, the pivotal year when Mr. Dylan broke out of the East Coast folkie bubble and made a cross-country journey. Victor took the wheel of a blue Ford station wagon, also joined by the folk musician Paul Clayton and the journalist Peter Karman. “It was a group of friends, all in the know, a nucleus of hip in America,” Mr. Wilentz said of the 1964 tour. “It was something special. The civil rights movement was going on.” The stops included a visit to the poet Carl Sandburg, in North Carolina, and a stay in New Orleans during Mardi Gras, where Mr. Dylan was denied entrance to a blacks-only bar. Back on the road, they heard early Beatles hits on the car radio, and Mr. Dylan feverishly scrawled lyrics in a spiral notebook. The first inkling of Mr. Dylan’s new fame came in London that May, when he performed at the Royal Festival Hall to an audience much larger than he normally drew in America. Victor draped his large frame over Mr. Dylan as they slipped through the ecstatic crowd. […] Returning to New York, they rushed to a studio, and Mr. Dylan “blurted it all out,” running through 11 new songs, “one after another without rehearsing.”

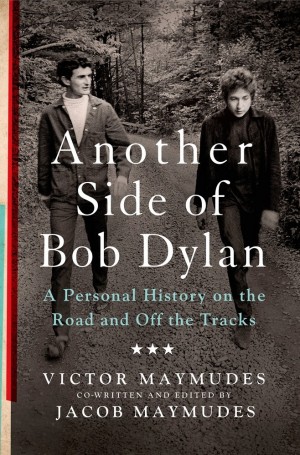

Improbable though this account seems, it squares with the one in Howard Sounes’s book Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan, which describes a single six-hour session, lubricated by Beaujolais, that resulted in the album “Another Side of Bob Dylan,” Mr. Dylan’s farewell at age 23 to the blues-inflected folk idiom he had conquered. Two songs — “Chimes of Freedom” and “My Back Pages,” with its soaring refrain, “Ah, but I was so much older then/I’m younger than that now” — signaled the next, visionary phase in Mr. Dylan’s work. Later that summer, he was invited to meet the Beatles at the Delmonico Hotel. The Dylan entourage brought along some marijuana. Mr. Dylan sat down to roll a joint, as Victor and others have reported, but he proved all thumbs, and Victor expertly took command. It was the first quality weed the Beatles had smoked, but the giddy conversation went on without Mr. Dylan. Exhausted from a string of late nights and a few drinks, “he passed out on the floor!” Victor remembers. Not that the book is an exercise in skeleton rattling or score settling. On the contrary, Victor reverently speaks of Mr. Dylan’s “greatness” and “genius” and rejoices in the “magical mystery tour” Mr. Dylan opened up for him — even as he remained curiously remote. The book suggests that the closer one got to Mr. Dylan, the more unknowable he became. MORE

BOOK EXCERPT: By 1955 a twenty-year-old Victor was entering the new culture of beatniks, music, art and drugs that Jack Kerouac would capture in On the Road, which was published in 1956. He and his friend Herb Cohen decided to open a coffee shop. They would become partners in the traditional sense; Herb would manage the business, and Victor would design and build  the look and feel of the cafe. That year, in all of the city, there wasn’t a single counterculture hangout or coffee shop. What they were planning was the first of its kind for Los Angeles: a home for live music and poetry; a reading room with a collection of hip books and ample space to play chess. It would quickly become a place where rebellion could thrive.

the look and feel of the cafe. That year, in all of the city, there wasn’t a single counterculture hangout or coffee shop. What they were planning was the first of its kind for Los Angeles: a home for live music and poetry; a reading room with a collection of hip books and ample space to play chess. It would quickly become a place where rebellion could thrive.

They found a perfect location in the heart of Hollywood at 8907 Sunset Blvd, the center of the Sunset Strip. Together they named the cafe: the Unicorn. For marketing they put posters up in liberal bookstores, music venues and any place that had a sense of hipness and a taste for folk music. Their posters were hand drawn with large hippie-looking characters playing guitars and sipping espressos. Swirling lines intertwined with slogans such as, “Where casual craznicks climb circular charcoal curbs for cool calculated confabulations” and “Espresso espression sessions on the patio.” The cafe was painted entirely black inside and pictures of nude women hung upside down on the walls. They were defining what hip was and they nailed it. Once the place was built, Victor would reach out to musician friends and poets to book performances at the cafe.

When they opened the doors, the Unicorn was instantly a hit. Queues would stretch down the street and around the block. They had tapped right into something bigger than themselves, a cultural divide precipitated by the strict mentality of the 1950s. What they created didn’t happen by chance, it was built by the entropy of a jaded youth reaching out for something to identify with. My father told me on many occasions about the feeling in the air at this time, as if everyone was waiting for something to happen. Some change of consciousness, like a giant wave that starts way out in the middle of the ocean. You know it’s coming, you just don’t know when it’ll arrive or how big it’s going to be. The venues for this revolution were being built, like the Unicorn; Victor would say they just needed a figurehead, a voice. They were waiting for someone to show up on the scene, someone who could reach across the oceans and connect people. MORE

RELATED: In an interview via Skype at the exhibit opening last weekend, [photographer Daniel] Kramer, 83, explained from New York City that he was intrigued by the power of Dylan’s lyrics after seeing him perform “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” on “The Steve Allen Show” in 1964. Not a music or showbiz photographer, Kramer tried to contact Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, to arrange a photo session. After six months of negotiating, Kramer went to visit Dylan at his home in Woodstock, N.Y., for a one-hour shoot. He stayed for five or six hours. Kramer mentioned that he hadn’t seen Dylan perform, so the singer-songwriter invited the photographer to a concert in Philadelphia [pictured, top of the page] . Dylan and his road manager picked up Kramer at his New York City apartment. That trip was when he really got to know Dylan. MORE

BOB DYLAN PLAYS THE ACADEMY OF MUSIC NOV. 21st, 22nd & 23rd