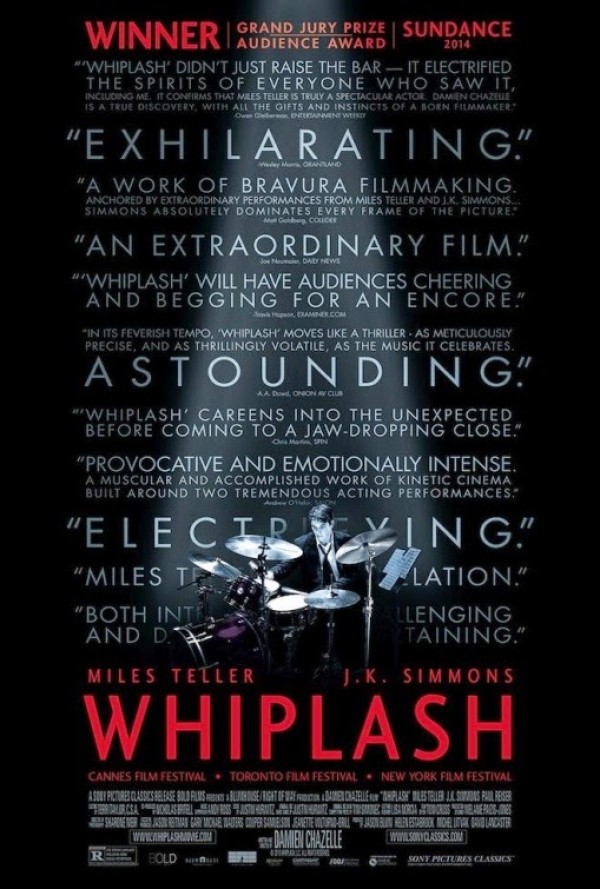

WHIPLASH (2014, Damien Chazelle, 109 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK Whiplash is a skilled filmization of a preposterous argument. Set in the cutthroat world of a music school jazz band writer/director Damien Chazelle’s breakout feature follows a drummer as he locks horns with an unhinged drill instructor of a music professor. Whiplash occasionally thrills with some expertly-edited big band performances but I never got so whipped up that I shook the horror I felt at the film’s attitudes toward jazz music, education and humanity in general. As a jazz fan I knew we were in trouble when it revealed that Andrew, the film’s teenage drummer, worships at the shrine of Buddy Rich. Rich was the jazz’s greatest “flash” drummer, known for his theatrical showboating but too much of a narcissist to excel at the supportive subtle interplay of the art at its highest form. If Rich is remembered today it is mostly for a foul-mouthed tirade clandestinely recorded by a band member while the whole group was being chewed out post-gig on the bus (Rich – “You’re playing like fuckin’ children out there!”). It’s as if Andrew’s love of the bombastic Rich conjures him to life. It’s Spiderman‘s J. Jonah Jameson, actor J.K. Simmons who summons Rich’s mercurial temper as the bombastic music professor Fletcher, the band’s taskmaster and performer of profane band room rants.

Rich’s brassy big band pomp is the spirit that hangs over the film’s musical performances (comprised of both standards and originals by Justin Hurwitz) making it easy to treat the music like an athletic endurance event. As Andrew masters his instrument he easily loses as much sweat and blood as a professional boxer. (the kit is often splattered like a murder scene). The film romanticizes an odd loneliness to being a musician. With Andrew, music isn’t a shared communicative experience, it is a black space into which he disappears with only the bald, hectoring head of Fletcher screaming insults at him.

For me, the film crosses a line it can never recover from when Fletcher repeatedly slaps Andrew full force in the face, supposedly to demonstrate Andrew falling off the beat (I don’t really think he is). It underlines the sick, authoritarian mindset not just explored but celebrated in this film. According to the constant bits of philosophy profanely spilling from Fletcher’s mouth, the path to excellence can only be achieved by surrendering to the pain of Fletcher’s sadistic mind-fuck. With Fletcher one minute you’re in, the next you’re brutally out. With great gravity he tells the class, “There are no two words in the English language more harmful than good job,” which sounds more like a dude with “daddy issues” than a sound educational strategy. Director Chazelle underlines this loopy philosophy by presenting Anthony’s dad (Paul Reiser) as a award-winning “Teacher of the Year” whose supportive attitude is what has kept Anthony from greatness. In the preposterous finale, Anthony literally turns away from his father’s open arms to dash back to triumph with his tyrannical task master.

The film celebrates that horrible ‘the reason America isn’t great is because it isn’t cruel enough’ philosophy that get blustered on talk radio, and making those ideas flesh only underline their senselessness. Surveying the classes new talent, Fletcher also quickly blows off the lone woman by saying she got there on her looks, and wallows in his sexist talk (“little girl” is a frequent taunt) passing it off as “authenticity.” Keeping to its conservative mindset story also doesn’t integrate any major African American characters, which can’t help but be noticeable in a film bathed in the history of jazz. No, this story is about two sweaty and irritated white guys, and that’s the kind of jazz they make.

It’s a shame that as our culture has short-changed jazz music for decades (a situation that has only worsened over the last decade’s record industry crash) that this nonsense is a high profile representation of the art.. Still, there’s no denying the musical performances have an unusual excitement, even if the film’s concept of jazz is frozen like the Tonight Show Band in 1970. When Fletcher’s indefensible teaching techniques pay off he says “How are we going to get another Louis Armstrong unless we push them?” While Whiplash lionizes figures like Armstrong and Ellington their actual lives (particularly champion mama’s boy Ellington) defy Chazelle’s “Pain = Genius” theory. Yes, hardship is often part of a great artist’s trajectory but saying that pain is the nurturing ingredient of genius is as misguided as saying it was the heroin that made Charlie Parker.