THE NEW YORKER: [Laura Poitras] turned to the documentary’s opening shot: a tunnel in Hong Kong, filmed with a narrow aperture, so that the camera appeared to be speeding through black space. A pattern of lights flashed overhead like Morse-code dashes. It created an ominous mood, evoking the beginning of David Lynch’s “Lost Highway.” The sound of wind rose and, in voice-over, an unidentified female—Poitras—read one of the first e-mails she received from Snowden: “At this stage I can offer nothing more than my word. I am a senior government employee in the intelligence community.”

Bonnefoy stopped the film. They were still polishing the soundtrack. Poitras said, “I’d love to try something electronic in it, and sort of move away from the wind.”

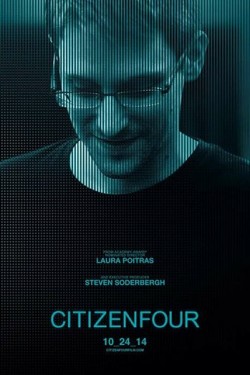

The voice-over continued, accompanied by a low vibrating sound, like an electronic sine wave, with eerie piano notes: “It will be your decision as to whether or how to declare my involvement.  My personal desire is that you paint the target directly on my back. No one, not even my most trusted confidante, is aware of my intentions, and it would not be fair for them to fall under suspicion for my actions. You may be the only one who can prevent that, and that is by immediately nailing me to the cross rather than trying to protect me as a source.” The wind sound rose and faded. “On timing, regarding meeting up in Hong Kong, the first rendezvous attempt will be at 10 a.m. local time on Monday. We will meet in the hallway outside of the restaurant in the Mira Hotel. I will be working on a Rubik’s Cube so you can identify me.”

My personal desire is that you paint the target directly on my back. No one, not even my most trusted confidante, is aware of my intentions, and it would not be fair for them to fall under suspicion for my actions. You may be the only one who can prevent that, and that is by immediately nailing me to the cross rather than trying to protect me as a source.” The wind sound rose and faded. “On timing, regarding meeting up in Hong Kong, the first rendezvous attempt will be at 10 a.m. local time on Monday. We will meet in the hallway outside of the restaurant in the Mira Hotel. I will be working on a Rubik’s Cube so you can identify me.”

Bonnefoy stopped the film again. “It’s actually quite nice,” she said of the wind sound. “Hearing it alone, it felt bombastic, but, like this, in the context, it’s actually more like he’s in a room, a space.”

Afterward, Poitras went home to her apartment, a few blocks away. She moved to Berlin in the fall of 2012, after years of being repeatedly stopped at airports by U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents. (She thought it might have something to do with a film about Iraq that she released in 2006.) Prenzlauer Berg, where Poitras has her studio, is Berlin’s Williamsburg; the coffee shops are upscale and have play areas inside. The neighborhood has become the center of the German capital’s small community of surveillance expats. Berlin is an ideal place for them; it’s hip and relatively cheap, with a respect for privacy that’s enshrined in law and custom. Germans attribute this to the legacy of the Gestapo and the Stasi, to which many of the American expats casually compare the National Security Agency. There’s a shiver of totalitarian ghosts, and totalitarian fantasies, amid the cobblestones and the Kinderspielcafes.

An English-language monthly, Exberliner, devoted its September issue to celebrating the scene. “Berlin’s Digital Rebellion,” the cover announced. “Whistle-blowers, Cypherpunks and Hackers: The post-Snowden resistance is right on our doorstep. Are you ready to join the fight?” The magazine featured an interview with Jacob Appelbaum, a “hacktivist” from WikiLeaks who is a friend of Poitras’s. Unlike many of the surveillance expats, Poitras speaks longingly of returning to America. In the past year, she and Greenwald have had disagreements with Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks. WikiLeaks believed that Poitras was too timid, and too preoccupied with her film, to release more of them.

Poitras doesn’t like to talk about her friction with WikiLeaks, or with the U.S. government. She doesn’t like to talk about herself at all. This reticence has complicated the making of the new movie, because, inescapably, she is one of its main characters. MORE