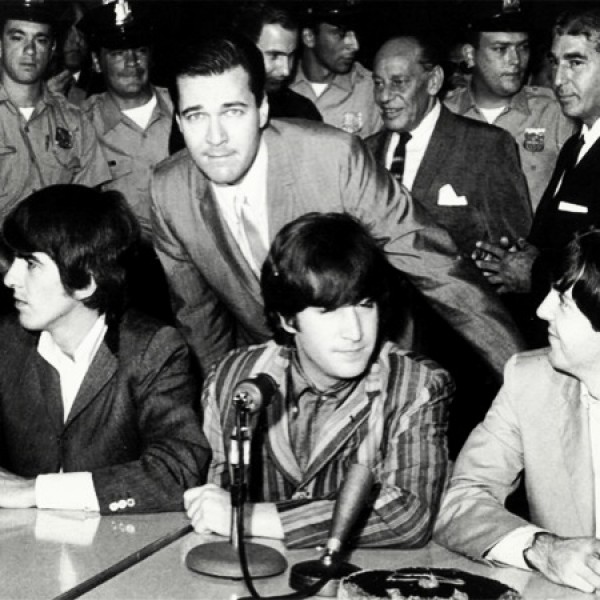

Hy Lit and the Beatles, Convention Hall, Philadelphia, 1964

BY JONATHAN VALANIA It is precisely 9:36 p.m. in West Philadelphia on the second splendidly summery September night of 1964, and exactly six minutes ago everything suddenly changed. For teenage Philadelphia, the calendar just flipped, along with everyone’s wig, to a new era. It will be years before anyone fully understands all the far-reaching implications, but this much is indisputably true: The hazy, crazy 1960s have officially begun.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA It is precisely 9:36 p.m. in West Philadelphia on the second splendidly summery September night of 1964, and exactly six minutes ago everything suddenly changed. For teenage Philadelphia, the calendar just flipped, along with everyone’s wig, to a new era. It will be years before anyone fully understands all the far-reaching implications, but this much is indisputably true: The hazy, crazy 1960s have officially begun.

OMIGOD, THEY’RE HERE! THEY’RE REALLY REALLY HERE!

For months, their songs have blared from the tinny speakers of transistor radios, and they’ve stared out hirsute and soulful from the glossy pages of fan magazines, and yeah, yeah, yeah-ed aphrodisically into the black-and-white kinescope  cameras of The Ed Sullivan Show, beaming live and direct into the nuclear family living rooms of the American night. And right here, right now, at Convention Hall, the kids in Philly are sharing the same rare air as the Fab Frickin’ Four!

cameras of The Ed Sullivan Show, beaming live and direct into the nuclear family living rooms of the American night. And right here, right now, at Convention Hall, the kids in Philly are sharing the same rare air as the Fab Frickin’ Four!

AAAAAAAIIIIIIIIEEEEEEEEE EEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!

From the outside–where more than a thousand ticketless Beatle- maniacs loiter hoping for a miracle, or at least a security guard with his back turned–you can almost see Convention Hall vibrating. Under the dusky evening sky, the illuminated windows of the hall create a shimmering jack-o’-lantern effect.

The cause of this seismic vibration is a deafening unstoppable sound, supersonic in pitch and intensity, like sticking your head inside the roaring jet engine of a 747 achieving takeoff velocity. It’s a sound that until recently had not been heard in the entire history of human listening: the sound of 13,000 teenage girls losing their shit under one roof.

AAAAAAAIIIIIIIIEEEEEEEEEE EEEEEEEEEEEEEE!

A shivery, quasi-orgasmic wave washes over the crowd as the four mop-tops, in dark velvet-collared suits and pointy-toed Cuban-heeled boots, finally–finally!–take the stage. But before they can even get out a single note, the Beatles are completely drowned out by the united mega-scream of 13,000 teenage girls. It will be years before scientists invent a concert sound system that’s louder than 13,000 screaming teenage girls.

AAAAAAAIIIIIIIIEEEEEEEEEE EEEEEEEEEEEEEE!

Philly Beatlemania begins with a riddle on a cold morning in December 1963 in the gray wake of the Kennedy assassination. Hymon “Hy” Lit–aka Hyski, aka Hyski O’Rooney McVautie O’Zoot, the No. 1 jock on WIBG, the city’s AM powerhouse–walks out to his car. On the windshield is the letter “B.” What in sam-hell is this? The next day there are two letters on the windshield: “B” and “E.” Day after that: “A,” followed by “T” the next day.

Every morning another letter–placed by an enterprising Capitol Records promo man, Hyski suspected. By the end of the week, the message on Lit’s windshield is complete: “THE BEATLES ARE COMING!”

It’s January 1964 and WIBG jocks Hyski and Joe “the Rockin’ Bird” Niagara, the two biggest names in Philadelphia radio, are knocking back complimentary beverages at a swanky “Meet the Beatles” cocktail party at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York. Disc jockeys and concert promoters from across the nation have been flown in to rub elbows and trade japes with the Fab Four. Hyski staggers out of the cocktail party with one thing on his mind: getting the Beatles to Philadelphia.

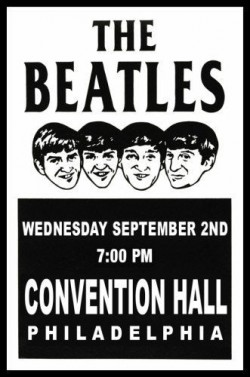

The next day he calls up William Morris, the Beatles’ booking agency, and asks what it will take. Twenty-five thousand dollars, they say. Hyski doesn’t even blink. He’ll be there tomorrow, he says, with a certified check. Thank you, Mr. Lit, says the booking agent. The Beatles will be on your doorstep Sept. 2.

Within weeks the Beatles appear on Ed Sullivan, which commands a Super Bowl-sized viewership, and seemingly overnight America falls hard for the Fab Four.

Tickets for the Philadelphia date go on sale in May, starting at $2.50 for the nosebleed seats and topping out at a whopping $5.50 for the floor. Convention Hall’s 12,037 seats sell out in 90 minutes. A mini-riot ensues when word of the sellout reaches the scores of ticketless Beatlemaniacs still in line. Hyski will be hit up with so many won’t-take-no-for-an-answer VIP ticket requests that when all is said and done and the Beatles have left town without even saying goodbye, he’ll be out $5,000.

In fact, the whole Beatles thing will turn out to be a really big headache, baby. What with the suits at the station giving him guff about that stunt he pulled on a Bulletin reporter who was writing trash about the Beatles fans the day after the concert was announced. Hyski gave out the reporter’s office number on the air and told listeners to call him up and scream  in his ear.

in his ear.

The Bulletin guy complained to his boss, who then turned around and gave Hyski’s boss an earful when they were out on the back nine together. At which point the bossman comes back to the clubhouse, calls up Hyski and tells him he’s off the air for a couple of days. No pay.

And on top of that, Hyski’s getting static from the local 7-Up guy, one of the station’s biggest sponsors, who had been demanding exclusive pouring rights for the concert. Hyski told Mr. 7-Up he didn’t need this crap from some glorified soda jerk and cordially invited him to shove it. “You ever heard of water?” said Hyski.

Well, the station brass wanted to suspend him for that too, but Hyski wasn’t having it. He was untouchable, and he knew it. He reminded them that he took a bullet for the team back in ’58 when the payola shit hit the fan–off the air for a year!–and now he was done taking bullets. He wasn’t interested in going on another “vacation.” You suspend me again and I resign, he told them, and the Beatles go with me. And that was the end of that, baby.

All summer long, WIBBAGE primes the pump, spinning a steady diet of Beatles wax, and broadcasting Fab Four reports with the urgency of a tornado alert. Ringo might have to have tonsils removed! Paul McCartney is still unmarried! Repeat: Paul McCartney is still unmarried!

Local papers stoke the hype. The Daily News runs a six-part series that asks the pressing questions of the day: “Is There Any Harm in Beatle-mania?” and “The Beatles: Do You Love Them or Do You Hate Them?” The DN even designates a special Beatles editor to handle all the Fab-related mail the paper receives.

In mid-August the Beatles commence their North American tour, an unheard-of 26 dates in 25 cities. Joining them on tour is 21-year-old Larry Kane, a Miami radio newsman who will serve as Brylcreemed Beatles chronicler, breathlessly delivering daily dispatches to a network of radio stations across the country like he’s Walter Winchell on the rooftops of London.

In time he’ll come to appreciate the Beatles’ artistry and realize the historic magnitude of the events he’s covering. But at the outset Kane fancies himself a serious journalist on a frivolous assignment. Square as a two-cent stamp, he’s deeply skeptical of the four longhaired Liverpudlians, an impression reinforced by his father, who tells him just before leaving for the tour, “Watch out, Larry. Those Beatles are trouble.”

Kane’s first encounter with John Lennon in a San Francisco hotel room doesn’t go so well.

“What’s your problem, man?” Lennon asks.

“What do you mean?” replies Kane.

“Why are you dressed like a fag ass, man? What’s with that? How old are you?”

“Well, it’s better than looking scruffy and messed up like you.”

But Lennon’s derision melts away when Kane turns around and asks him about Vietnam, a topic Beatles manager Brian Epstein has forbidden the boys to talk about. Kane is surprised by how informed and articulate Lennon is about his objection to the war. Lennon is surprised to hear an American journalist ask him a non-moronic question. After a rocky start, Kane eventually earns the Beatles’ respect because, unlike the cynical press corps that greeted the band in every city, he never talks down to them.

The Beatles crisscross the country in a chartered turboprop dubbed “the Electra,” touching down in each city long enough to whip the wiggling pubescent throngs into a hysterical lather for 38 minutes before taking off again.

Teenage girls going crazy for idols is as old as Sinatra, and Elvis’ swivel-hipped reign only upped the ante. But Kane starts to notice a significant difference. Not only is the decibel level and intensity of the audience reaction off the scale, but the degree to which these kids are willing to buck authority — breaking through barricades, accosting police officers and engaging in all manner of subterfuge, such as dressing up as hotel chambermaids just to get closer to the object of their desire — is unprecedented. As the Day-Glo youthquake of the ’60s erupts, it will become apparent that this was a harbinger of things to come.

The news reports of all of this youth gone wild in the streets doesn’t go unnoticed by Frank Rizzo, then-deputy commissioner of Philadelphia’s finest. The Big Bambino is gonna make damn sure the same crap doesn’t happen on his watch.

The news reports of all of this youth gone wild in the streets doesn’t go unnoticed by Frank Rizzo, then-deputy commissioner of Philadelphia’s finest. The Big Bambino is gonna make damn sure the same crap doesn’t happen on his watch.

When President Johnson came to town to address the graduating class of Swarthmore in the spring of ’64, the police held just one meeting to strategize security, and it was open to the press. For Operation Beatle, as it was dubbed, Rizzo holds three closed-door security meetings, using a slide projector to plot out every possible security breach and problem area at Convention Hall. The good news is that the hospital is only 24 seconds away.

Rizzo would soon face down a much bigger problem than unruly teenage girls. In North Philadelphia, tensions between the black community and Rizzo’s force are about to explode. On the night of Aug. 28 at the corner of 22nd and Columbia, a black police officer gets into a shoving match with an inebriated black woman. A crowd gathers, and bottles and bricks began raining down as police reinforcements are called in. By 10:30 p.m. the melee on Columbia Avenue has escalated into a full-blown riot. Before dawn Rizzo is on the scene, backed by 600 uniformed policemen.

At the very moment the riot is breaking out in North Philadelphia, the Beatles are camped at the Hotel Delmonico in New York for a two-day run at the Forest Hills Tennis Stadium. Something is happening in the hotel room that, had he found out, would have given Rizzo apoplexy: Bob Dylan is passing a joint to John Lennon. This act of stoner generosity will almost single-handedly light the fuse of the psychedelic ’60s.

Dylan just assumed the Fab Four were all seasoned pot smokers, having mistaken the “I can’t hide” line in “I Want to Hold Your Hand” for “I get high.” Lennon warily hands the joint to Ringo Starr. Blissfully unaware of pot-smoking etiquette, he proceeds to bogart it down to the ashes. Another joint is quickly rolled.

Giddy with the “profound” philosophical insight of the newly high, Paul McCartney announces he has figured out the meaning of life. He asks an assistant for a pen and a piece of paper. He simply must write this down before he forgets it. The next morning he’s disappointed to discover that the only thing written on the piece of paper is the cryptic phrase, “THERE ARE SEVEN LEVELS.”

The next night, after another breathless run-for-your-life backstage escape, the Beatles helicopter from New York to Atlantic City for a few days of surf-and-sun R&R prior to their concert at the A.C. Convention Center. But the Beatles are fast becoming prisoners of their own fame, and the several-thousand-strong teen mob that rings the perimeter of the Lafayette Motor Lodge on North Carolina Avenue keeps them roombound for the duration of their stay.

The Beatles tell reporters they’re playing Monopoly, but the truth is a bit more decadent. Invited up to the Beatles’ suite on the first night of the A.C. stay, Larry Kane is taken aback when he enters the room and sees a line of 20 heavily perfumed women in low-cut dresses and painted faces. Standing off to the side like a lion tamer, a man in a suit turns to the Beatles party and says, “Take your pick.”

“You heard the man,” cackles Lennon. “Take your pick.”

The next night, on the way to the venue, the Beatles are nearly torn to pieces when a mob of teenagers surrounds the motorcade and smashes its way into one of the chase cars before police break through and restore order. The next day the Atlantic City police smuggle the Beatles out of town in the back of a Hackney’s Fish truck while a decoy motorcade takes off in the opposite direction. Several miles west of Atlantic City, the Beatles switch transport, trading the fish truck for the comparatively cushy confines of a chartered bus heading to Philadelphia. The Jersey roads are lined with teenagers hoping for a glimpse of the passing motorcade.

The vigil outside Convention Hall begins with four teenage girls who show up at 2:30 on the morning of the concert. Police quickly dispatch a cab and send them home. But reinforcements soon follow, and by 3 p.m. more than 1,000 teenagers are outside Convention Hall chanting, “WE WANT THE BEATLES!”

The vigil outside Convention Hall begins with four teenage girls who show up at 2:30 on the morning of the concert. Police quickly dispatch a cab and send them home. But reinforcements soon follow, and by 3 p.m. more than 1,000 teenagers are outside Convention Hall chanting, “WE WANT THE BEATLES!”

A contingent of crewcut boys stage a wildly unpopular anti-Beatles protest, holding up signs that make the hard-to-argue claim that the Fab Four are unfair to barbers. Oh, that hair! Nobody older than voting age can get over that outrageously “long” Beatle hair. Local columnist Rose DeWolf refers to them as “the barber-shy quintet.” A wag from the Inquirer had earlier opined, “The haircuts look like some drunken barber had at them with a soup bowl and pair of tinsmith’s shears.”

Word has slipped out that the Beatles are staying at the Warwick Hotel. Sandy Hankin and her gal pals from the Northeast have prepared for this eventuality. Just about every day in August — when they weren’t busy seeing A Hard Day’s Night 28 times — they would take the bus and the El into Center City and case out the back entrances and freight elevators at the Warwick and the Bellevue Stratford, befriending maids who promised to divulge the Beatles’ room numbers. By mid-afternoon there are 400 girls waiting outside of the Warwick.

At 3:51 the Beatles’ caravan slips into the back entrance of Convention Hall, somehow eluding the notice of the feverish crowd out front. Four cots are set up in the Beatles’ dressing room — Rizzo had nixed any plans to stop at the Warwick before the show — along with five bottles of J&B scotch, 25 fish-and-chips dinners from Bookbinder’s and bagload after bagload of the 50,000 fan letters, including 88 marriage proposals, sent in by WIBBAGE listeners. When it’s all over, the radio station will give away the cots as prizes to station callers, along with the Beatles’ unused toilet paper.

The first Beatle Hy Lit greets is Paul McCartney, who asks the not-unreasonable question, “What is a Hy Lit?” Hyski smiles and tells him it’s a cologne, baby.

The Beatles’ handlers try to clear the dressing room, but Hyski isn’t gonna get kicked out of his own party. He reminds his guests that he paid for everything they see around them. Okay, say the handlers in polite British accents, everybody but Mr. Hyski has to leave.

Behind the toothy grins and urbane Goon Show wit the Beatles produce on cue at every strobe-flashed airport, hotel and press conference, there’s a little-publicized dark side to Beatlemania — menacing letters, bomb hoaxes, telephoned death threats.

A week before the Beatles arrive in town, psychic Jeane Dixon — who rose to prominence by foretelling JFK’s assassination in Dallas — predicts the Beatles’ plane will crash on the flight out of Philadelphia. The prediction rattles the Beatles’ cage — especially Lennon, who gravely confides to Larry Kane that he can’t stop thinking about Buddy Holly dying in a plane crash.

George Harrison gets Dixon on the phone and asks her about the prediction. He reports to the Beatles’ touring entourage that Dixon was “reassuring,” and told him it was safe for the Beatles to fly. During downtime at Convention Hall, Kane pulls Harrison aside.

“George, we’ve been hearing things, and reading about this woman who’s predicting a plane disaster,” Kane says.

“Uh, normally I just take it with a laugh and a smile and a pinch of salt, thinking, you know, she’s off her head,” Harrison replies. “But, y’know, it’s not a nice thing to say, especially when you’re flying almost every day. But just hope for the best, and keep a stiff upper head, and away we go. If you crash, you crash. When your number’s up, that’s it.

At 5 p.m. a press conference commences in the bowels of Convention Hall. Among the media pack busily sharpening its knives is a reporter from Time, a network TV news crew and reporters from the DN, the Inquirer and the Bulletin. Also on hand: 25 lucky WIBBAGE listeners, Rizzo’s boys in blue and a contingent of, um, South Philadelphia cement-mixing industry executives. The Fab Four sit at a table, smoking and sipping sodas, gamely answering the press’ predictably belittling questions.

“Will you ever get your hair cut?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” says Starr. “We might get bald.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” says Starr. “We might get bald.”

“What do you think of serious music?”

“It’s rock ‘n’ roll,” says Lennon. “All music is serious. It depends on who’s listening to it.”

“Do you think your popularity will last?”

All four reply in unison: “No.”

“What have you heard about Philadelphia?”

“Riots,” Lennon says.

By the end of the press conference, the crowd in front of Convention Hall has swelled to 7,500. They’ve come from all over: the Northeast, South Philly, Center City, Upper Darby, Gladwyne, Cherry Hill, Roxborough, Olney, Logan, Bala Cynwyd. They arrived by Daddy’s car and by bus and by the trainload on the Frankford El, singing Beatles songs to the clickety-clack beat of the train tracks.

In the simmering heat, they’re lined up for blocks on the sidewalks leading up to Convention Hall. Every time a shadow passes by one of the windows on the upper floor of Convention Hall somebody gasps, “I saw George!” or “I saw Paul!” and the shriek dominoes through the line for blocks.

At 6:20 p.m. the doors finally open and the teen mob starts filing in. Performers Jackie DeShannon and Clarence “Frogman” Henry warm up the crowd, but few seem to notice.

Backstage, Hyski is pretty much at the end of his rope, baby. Everyone wants something. The Beatles want Coke for their scotch, Rizzo wants to knock heads if anyone steps out of line, and every parent in the tristate area wants their snot-nosed kid to meet the Beatles. And they all want Hyski to make it happen.

The final straw comes when one of the Beatles’ handlers takes Hyski aside and points out girls in the audience that the boys would like to meet privately. Well, that was the final nail in what was fast becoming a very uncool coffin, baby. Beatles or no Beatles, Hyski don’t play that game. He throws his arms in the air and storms off.

At 9:30 on the nose, the Beatles take the stage. The crowd goes ballistic, launching a loving hailstorm of jellybeans, jewelry, lipsticks, sneakers and marshmallows, some of the items inscribed with marriage proposals. The Fab Four kicks into “Twist & Shout.” Their lips are moving and they’re strumming their guitars, but the only thing anyone can hear is: AAAAAAAIIIII IIIEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE EEEEEEEE!

This is followed by “She Loves You,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “Hard Day’s Night,” among others. Each song is gamely executed through the hollow sound system, and each one rendered completely mute by the mega-scream of 13,000 teenage girls. (The next day the Daily News will sum it all up succinctly with one of its patented four-alarm headlines: “DAZZLED DAMSELS DECIMATE DECIBELS IN DELIGHTFUL DELIRIUM.”)

This is followed by “She Loves You,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “Hard Day’s Night,” among others. Each song is gamely executed through the hollow sound system, and each one rendered completely mute by the mega-scream of 13,000 teenage girls. (The next day the Daily News will sum it all up succinctly with one of its patented four-alarm headlines: “DAZZLED DAMSELS DECIMATE DECIBELS IN DELIGHTFUL DELIRIUM.”)

As has been the case at every show, the crowd surges toward the stage. One of the cops in charge tells Hyski to stop the show to tell everyone to go back to their seats.

Hyski is incredulous. “You want a riot? Stop the show and you’ll have a riot. I’ll hold you responsible!”

No, baby, we’re gonna stay real cool and calm-like and obey Hyski’s prime directive: When you don’t know what to do, don’t do nothing. Just let ’em scream their brains out. It’ll be fine.

Besides, what are you gonna do–shoot ’em? The bullets and billy clubs of a few hundred cops would be completely useless against 13,000 screaming teenage girls. Thirteen thousand screaming teenage girls freefalling in a vertiginous swoon. Thirteen thousand storm-tossed rag dolls in a riot of hormones and heartache. Thirteen thousand teenage girls in a tear-streaked ponytail-flippin’ frenzy of desire and idolatry. Thirteen thousand tingling girls hyperventilating in a zombie trance of ecstatic want and need. Biting their fists. Pulling their hair out. So close and yet so far.

AAAAAAAIIIIIIIIEEEEEEEEEE EEEEEEEEEEEEEE!

To the adults on hand, which is to say the cops, the ushers and the assorted parents with cotton stuffed in their ears, the deafening shrieks are unnerving. Are they dying?

To the adults on hand, which is to say the cops, the ushers and the assorted parents with cotton stuffed in their ears, the deafening shrieks are unnerving. Are they dying?

Naw, we’re gonna live forever. That’s what any one of ’em would say if you asked and they could somehow hear you.

In truth, though, they all died a little bit that night–the girls, Hyski, Rizzo, the crewcut ’50s. After all, he not busy being born is busy dying–Bob Dylan said that.

Some in the adolescent throng had just recently started getting their heads around the idea that we all die eventually–all of us, even the Beatles. Comprehending this was one step closer to being grown up, one step closer to the end of innocence. More important, though, had those 13,000 screaming teenage girls ever felt more alive? Never. Some, in fact, would never feel this alive again.

THIS STORY ORIGINALLY APPEARED ON THE COVER OF THE APRIL 28TH 2004 OF PW