FRESH AIR

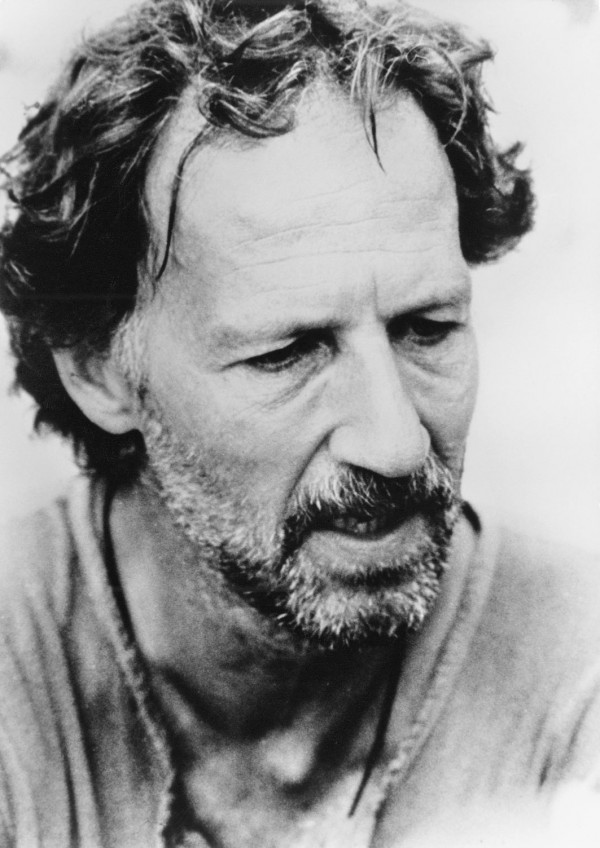

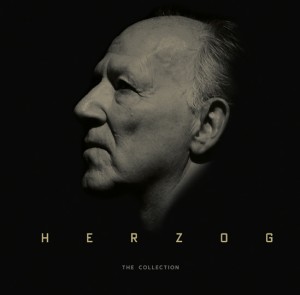

There are lots of good filmmakers, but only a handful are always, unmistakably themselves. One of these is Werner Herzog, the 71-year-old German director who now lives in L.A. Herzog has done things nobody else would do for a film — like trying to tug a 350-ton steamship over a small mountain. This has made him notorious as a wild, love-him-or-hate-him monomaniac — an image he’s been canny enough to milk. Herzog rose to fame as part of the New German Cinema, a ’70s boom that also included Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wim Wenders and Margarethe von Trotta. Starting in 1970 with Even Dwarfs Started Small, an anarchic tale of rebellion by a group of dwarfs, he unleashed a torrent of 10 films — including Nosferatu and Fitzcarraldo — that remain the heart of his achievement. All those movies, and six later ones, are included in the tremendous new boxed-set, Herzog: The Collection. Some of them are great, others are good, and a couple are truly terrible. Yet every single one has something going on. Herzog has never been limited by anybody else’s idea of propriety, good sense or artistic neatness. He pushes us into unsettling mental spaces that make the strange familiar and the familiar strange.

His best and most daring movies may be two early documentaries — Fata Morgana, a surreal creation myth shot in the Sahara; and Land of Silence and Darkness, an almost mystical story centering on a woman who has gone deaf  and blind. Yet they are a tad forbidding. The best way into Herzog’s work is through his most delightful film, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser. It’s based on the true story of a young man who, after being kept alone in a cellar for the first 17 years of his life, walks into the streets of 1820s Nuremberg. What ensues is the collision between a German society that thinks itself civilized and this strange, grown-up wild child, astonishingly played by Bruno S., a street musician who’d spent time in mental institutions. Filled with sympathy for Kaspar, the movie explores one of Herzog’s trademark themes — the role of the individual who, in profound and revelatory ways, doesn’t remotely fit into society. That’s true in a very different way of the hero of the film to watch next — Aguirre, the Wrath of God. Shot along the Amazon in Peru, it tells the story of a doomed group of Spanish conquistadors searching for El Dorado. They’re led by the blond-tressed, hubristically loony commander, Don Lope de Aguirre. He’s indelibly played by Klaus Kinski, the wacko actor who starred in several more Herzog films and became the subject of Herzog’s amusing documentary, included here, titled My Best Fiend.

and blind. Yet they are a tad forbidding. The best way into Herzog’s work is through his most delightful film, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser. It’s based on the true story of a young man who, after being kept alone in a cellar for the first 17 years of his life, walks into the streets of 1820s Nuremberg. What ensues is the collision between a German society that thinks itself civilized and this strange, grown-up wild child, astonishingly played by Bruno S., a street musician who’d spent time in mental institutions. Filled with sympathy for Kaspar, the movie explores one of Herzog’s trademark themes — the role of the individual who, in profound and revelatory ways, doesn’t remotely fit into society. That’s true in a very different way of the hero of the film to watch next — Aguirre, the Wrath of God. Shot along the Amazon in Peru, it tells the story of a doomed group of Spanish conquistadors searching for El Dorado. They’re led by the blond-tressed, hubristically loony commander, Don Lope de Aguirre. He’s indelibly played by Klaus Kinski, the wacko actor who starred in several more Herzog films and became the subject of Herzog’s amusing documentary, included here, titled My Best Fiend.

More than just a portrait of colonial madness, Aguirre, the Wrath of God is a dazzling study in another of Herzog’s themes — humankind’s relationship to landscape and nature, about which Herzog is not sentimental. While in the Amazon shooting his famous film, Fitzcarraldo, he riffs on that subject in filmmaker Les Blank’s documentary Burden of Dreams. Herzog is an enthralling talker. His audio commentaries on these disks are classics of the form. Now, not all the movies are classics. By the time he made his African slave-trade film Cobra Verde in 1987, many people thought he’d run dry. Yet this great chronicler of cussèd, obsessive heroes kept on making movies in his own cussèd, obsessive way. And about 10 years ago, things changed. With the release of his terrific 2005 documentary Grizzly Man, Herzog became one of those rare artists — like Philip Roth or Leonard Cohen — who enjoyed a second flowering after the age of 50. Indeed, nowadays he’s a beloved icon, a man who sometimes seems to be everywhere — making acclaimed docs like Cave of Forgotten Dreams and Encounters at the End of the World, playing the villain in Tom Cruise movies and lending his voice to cartoons about penguins, and directing features like the upcoming Queen of the Desert, which stars Nicole Kidman as the famous British explorer Gertrude Bell. Because he’s so adored, Herzog has at moments fallen into shtick during interviews — Herzog doing Herzog. But he’s never gone soft or commercial or betrayed the driven filmmaker who made those audacious early movies. He’s never settled into chasing Oscars. Instead, like one of the wayward heroes in Herzog: The Collection, he has kept plunging into the unknown, sometimes blindly, sometimes not. MORE