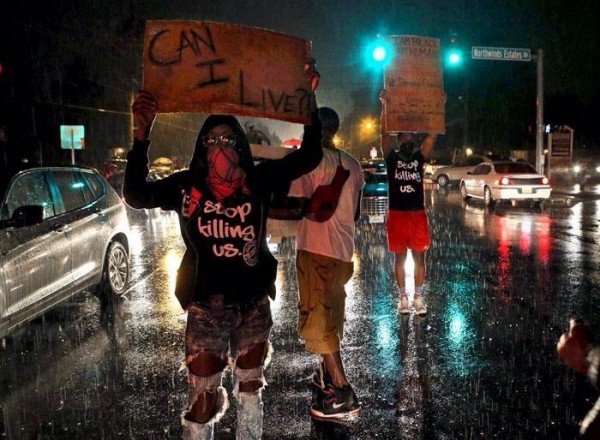

Via Twitter/photographer unknown

BY JEFF DEENEY I grew up in suburban Philadelphia in the 80s. It was a time when working class families were leaving their row homes in a city they considered increasingly black and dangerous in droves for single houses on tree lined streets in nearly all white townships not far away, maybe ten miles, but in many ways worlds apart. By 1985, when the bomb dropped on the MOVE house and it seemed like Philly was death spiraling into apocalypse my parents watched the chaos over dinner in Delaware County marveling at what good fortune we had to have left the same neighborhood a few years before it went downhill. The notion was cemented among white flight families had that crime happened “there” – i.e, the city, where black people live – and not “here.” They needed police to keep them in line; we needed police to get cats out of trees.

BY JEFF DEENEY I grew up in suburban Philadelphia in the 80s. It was a time when working class families were leaving their row homes in a city they considered increasingly black and dangerous in droves for single houses on tree lined streets in nearly all white townships not far away, maybe ten miles, but in many ways worlds apart. By 1985, when the bomb dropped on the MOVE house and it seemed like Philly was death spiraling into apocalypse my parents watched the chaos over dinner in Delaware County marveling at what good fortune we had to have left the same neighborhood a few years before it went downhill. The notion was cemented among white flight families had that crime happened “there” – i.e, the city, where black people live – and not “here.” They needed police to keep them in line; we needed police to get cats out of trees.

We kids knew better. Crime doesn’t only happens in poor black neighborhoods; we knew that because we participated in the same kind of criminal activity that young black kids get locked up for every day. We just rarely got caught committing crimes, because there was so much less law enforcement involvement in the lives of white teenagers in the suburbs. When we did get caught we usually walked because suburban criminal justice systems weren’t primarily concerned with inflicting potentially life ruining penalties on children in their communities. Unlike Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, we never had to worry about a cop drawing a gun on us.

Perhaps the working class 80’s heavy metal vomit party crowd I grew up with was worse than most; perhaps some percentage of teens in any class group are prone to delinquency, but throughout my formative years I was witness to and frequently a participant in a lot of crime. It was mostly petty stuff – though, that was me; many kids I knew were into pretty serious things. I had a phase where I shop lifted. I started drinking heavily at the age of 12. By the age of 13 I had been exposed to drugs like cocaine and PCP. I wasn’t into property destruction (I was overweight and couldn’t run very fast and was bound to get caught) but friends of mine destroyed incredible amounts of property. Some kids like to spray paint and tag with markers; some liked to fist fight. In all, we were a pretty rowdy bunch.

I had a friend who built pipe bombs. He even experimented with loading the cylinder full of nails before adding the gunpowder to see how much more damage he could do by spraying shrapnel. I remember one day he took me to a local pond to show me how he used a waterproof fuse on his latest creation. He lit it, and hurled it into the water. After a long pause there was a muted boom, followed by the water’s surface burping upward in a Gaussian curve. The settled surface slowly turned a smoky grey, and a few moments later fish corpses bubbled up by the dozen. My friend smiled devilishly, very satisfied with the result.

As we got older, other groups of kids got in on the action. There were the jocks who liked to drink and then jump random strangers. There were stories of groups of kids driving into the city to stomp down homeless people, or shoot at drug addicts with pellet guns for sport. When different cliques got into fights the results were increasingly vicious, and people got seriously injured. By this point drug dabbling morphed into entrepreneurial kids with a taste for rumbling launching full scale drug distribution operations. It was mostly weed, but not entirely. You could get meth, or coke, or dust, too. This is in your perfectly average, prototypical, in fact, white American suburb.

What we never had were interactions with the criminal justice system. In fact, the local political and law enforcement structure bent over backwards to keep juvenile delinquents out of the system. I got picked up one night when friends of mine were vandalizing cars (I told you I couldn’t run too fast); the police took me to the station and held me until my parents came to pick me up. This happened to nearly all my friends; if they had some run in with the police they were always allowed to be released to their parents. The police never filed formal charges generating court dates in the juvenile justice system that would take time and money to resolve, and potentially harm our futures by giving us a record.

After keg parties were busted the cops would haul bus loads of kids into the station but none of them were cited. They got warnings from the cops and then stern lectures from their parents. Even in instances where kids got arrested for more serious crimes, if their parents knew a cop, or a township official, or someone in local politics it could be made to disappear. Kids who had repeated run ins with the cops were considered troubled; it was probably something happening at home that was making this otherwise good kid act out.

This privileged air of untouchability follows white children into young adulthood. At college we were free to abuse whatever drugs we wanted, in whatever quantities and the students who supplied the school with them never had to worry about a narcotics SWAT team blasting the door off the hinges in the middle of the night. Every night on a college campus somewhere a party devolves into a drunken brawl, or a sporting event spirals into a minor riot. The people behind these outbreaks of disorder rarely catch serious criminal charges. In fact, they’re really even seen through a criminal lens. It’s just college. It’s nearly impossible to imagine the same law enforcement response to similar disorder in a black community.

It’s obviously not impossible for white people to go to jail. In fact, some of the dudes I grew up with – the heavy metal kids, more on the working class end of the suburban spectrum who couldn’t afford flashy attorneys – eventually got locked up. If they were selling drugs, it was because they got sloppy and reckless and drew attention to themselves. For others it was drinking and driving, or too much public fighting. Either way, they only finally had a serious interaction with the criminal justice system that resulted in real consequences after years and years of chronic, relentless offending. They only eventually hit the wall because they were so determined to run into it. In the meantime, the system gave them every possible break; police looked away the maximum number of times.

Now I’m an adult social worker in Philly’s criminal justice system. Every day I see kids catching cases for the minor criminal acts we committed with abandon as white suburban teenagers. For selling way less coke than guys in my town a black teenager will get a felony charge. Smoking a blunt on the corner will get you frisked and booked in Southwest Philly; we used to openly smoke weed on the campus quads in between classes and never had to worry about police harassment. If a black kid in North Philly is caught committing the kind of vandalism we used to engage in all the time, he gets a juvenile probation officer instead of a courtesy call to his parents from the local police district. If a fight breaks out on school grounds the result is less likely to be school administrators talking it out between students and more likely to find the child expelled under a zero tolerance policy.

I don’t want to give readers the sense that I feel like the justice system was too lenient on me and my friends growing up in white suburbia. In fact, I think they did the right thing using their discretion to let so much minor crime slide rather than always bring the full force of the law to bear in a way that transforms bad, impulsive decisions made by children into potentially life altering consequences that mire someone in an increasingly punitive system with a permanent record that can follow them throughout their life. It’s the way our laws are applied in such a dramatically discriminatory fashion, where some communities are deemed more crime-prone than others and subjected to relentless policing, more frequent arrests and hair trigger responses that has created a problem those of us who work in the system have known about for many years, that is in the national spotlight once again after the death of Mike Brown.

This disparity needs to be addressed so badly part of me could almost get on board with a Modest Proposal that would extend the same treatment black men receive to the rest of society. If we can’t agree that black communities are over-policed and unnecessarily criminalized, let’s at least accept that much of the same crime exists unaddressed in white communities. Let’s begin SWAT-style narcotics raids on Ivy League dormitories where we know kids are using and selling drugs. Let park military vehicles and tear gas equipped warrior cops outside of every major college sporting event, because we know sometimes they become disorderly. The only reason I couldn’t be totally sold on such an idea is that I know from my work how cruel our penal institutions are, how brutal our police can be and I don’t wish those interactions on anyone, let alone want to voluntarily submit more people to it. But the fact is that it’s our unequal application of our criminal justice policies that allow foot dragging on reform. Something tells me that if the sons and daughters of federal judges and captains of industry were getting their teeth bashed in by narc cops on Saturday night fraternity and sorority raids, what we consider to be criminal behavior in need of enforcement would quickly change.

The system went easy on us, and as a result, we thrived. Even some of the most reckless teenagers I knew, who engaged in what would be considered truly criminal behavior by any objective measure, went on to be productive members of society (yes, even Bomb Boy). Years later, we’re not still reporting to probation officers; we went to college, and we have jobs and families of our own. But this is a privilege available to some and not others, based overwhelmingly on where you grew up and the color of your skin. Mike Brown was a shoplifter. So was I. Mike Brown smoked weed. So did I. But Mike Brown is dead by a police officer, and years later I’m alive, here writing this. Why? Because I’m not Mike Brown, and that’s where the problem lies.