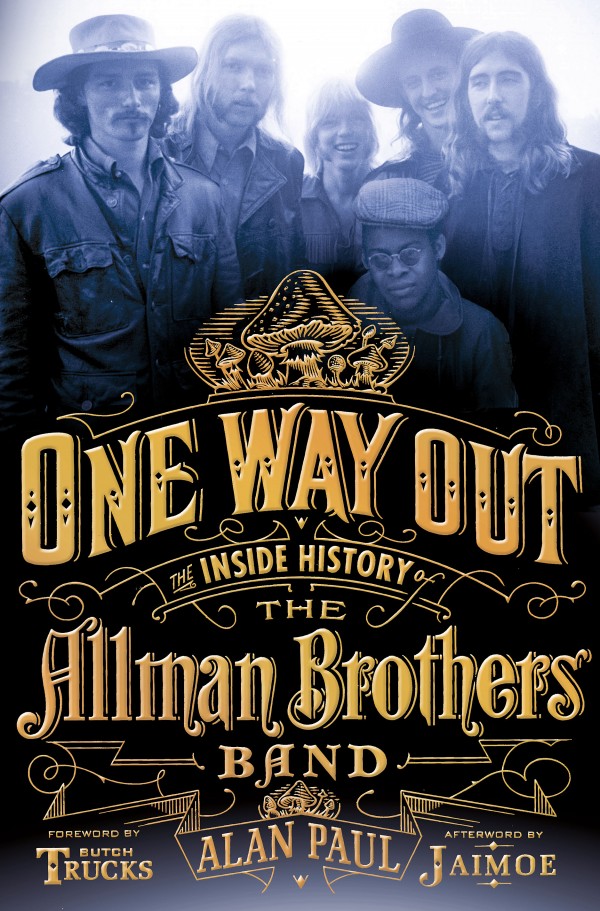

BY ED KING ROCK EXPERT What makes a band a band and not just a group of musicians who play music together? Jazz musicians often play together, but they rarely form bands. Supporting musicians flow in and out behind a clear band leader, the way they did behind Miles Davis, helping to drive his many stylistic permutations. What’s the value of a band, why do people bother? In rock ‘n roll, countless collections of musicians undeniably exist as a band despite barely qualifying as musicians. Alan Paul’s oral history of the Allman Brothers Band, One Way Out, is a portrait of a band in the fullest sense, despite the band losing its guiding light as it hit its stride, despite being fueled by strong jazz influences and considering themselves progressive musicians rather than the forefathers of shit-kicking Southern Rock that their heritage and a rock fan’s own regional prejudices might suggest. Despite not making more than a few measures of music that ever moved me, the experiences dozens of musicians in the extended Allmans family share speak to the value of playing in the band.

BY ED KING ROCK EXPERT What makes a band a band and not just a group of musicians who play music together? Jazz musicians often play together, but they rarely form bands. Supporting musicians flow in and out behind a clear band leader, the way they did behind Miles Davis, helping to drive his many stylistic permutations. What’s the value of a band, why do people bother? In rock ‘n roll, countless collections of musicians undeniably exist as a band despite barely qualifying as musicians. Alan Paul’s oral history of the Allman Brothers Band, One Way Out, is a portrait of a band in the fullest sense, despite the band losing its guiding light as it hit its stride, despite being fueled by strong jazz influences and considering themselves progressive musicians rather than the forefathers of shit-kicking Southern Rock that their heritage and a rock fan’s own regional prejudices might suggest. Despite not making more than a few measures of music that ever moved me, the experiences dozens of musicians in the extended Allmans family share speak to the value of playing in the band.

Reading One Way Out, I learned that the brothers Allman, Duane and Gregg, were born into the blues, as their father was murdered when the boys are infants. Although only a year older than Gregg, teenage Duane becomes the man of the house and Gregg’s father figure. In his short time, Duane is remembered not only a gifted musician, playing lead guitar on Muscle Shoals sessions as a teenager, but a leader. Through communal living, psychedelics, and free concerts, Duane drills a diverse set of ambitious musicians, centered around the gruff blues wail of kid brother Gregg. Bandmates remember Duane as a do-as-I-say-not-as-I-do leader, driving home lessons of professionalism between episodes of nodding off.

By the time they landed on my teenage rock radar, the Allman Brothers Band had already lost two founding members, lead guitarist Duane and bassist Berry Oakley. Their 1973 hit song “Ramblin’ Man” was an established staple of both the AM and FM airwaves. Growing up in the ‘70s, I didn’t like country music or country-rock, but the song’s hooks were unavoidable. Thinking about the song now, as I write this, a flood of half-remembered lyrics, guitar licks, and instrumental passages rush to the surface. I didn’t know who was who in the band or that a couple of key members had died. The only full album I’d ever heard by them was Eat a Peach, which my uncle owned on 8-track. As a little kid I’d sit in his room for hours and listen to his collection of hippie 8-tracks: Traffic, the Band, Dylan, Hendrix, Joe Cocker, Leon Russell… I never said anything about it to my uncle, but Eat a Peach was the only turd in his collection.

I didn’t become fully aware of the connection the Allmans had with their fans until a high school group led by a mysterious kid in the grade above me played a school assembly. At the time my friends and I were engaged in starting our own band, a punk band. We’d been getting together in garages and basements for a couple of months. Only our drummer could actually play his instrument, but we managed to work up a dozen crude originals and half-baked covers. A good deal of our weekly rehearsal time was taken up by goofy teenage boy stuff: eating pizza; recounting skits from SCTV and Saturday Night Live; cracking dick jokes; and imitating rock stage moves, from Townshend’s windmill strum and “Won’t Get Fooled Again” slide to Daltrey’s mic swing, the Beatles’ harmonizing mop-top shakes, Mick Jones’ guitar prance, and inevitably our rhythm guitarist’s knock-kneed take Elvis Costello’s stance from My Aim Is True and the “Pump It Up” video. Our covers included whatever three-chord songs we could figure out, at least to a point. Sometimes we’d learn a three-chord song like the Romantics’ “What I Like About You” and bypass the sections still beyond our comprehension, like the instrumental build up that led up to the harmonica solo. The whole point of the song was to reach that climactic moment when everyone shouted “Hey!” and the harmonica solo kicked in. It didn’t matter that none of us really knew how to play harmonica. One of us would blow into one as hard as we could and hoped to hit on a few of the notes by chance.

We bought a few songbooks in hopes of expanding our repertoire, including The Compleat Beatles; a book of solo Beatles sheet music; a Costello collection; and even a punk rock collection of songs by Sire artists, including Talking Heads, Blondie, and Richard Hell & the Voidoids! We were only capable of reading the chord charts, not the notes themselves (if only I could have read the notes and possibly unlocked those wicked Robert Quine solos in “The Blank Generation”), but almost any song we explored involved a fourth chord or a chord involving minor 7ths or 6ths—or even one of those mysterious diminished or augmented notes.

We were well aware of the fact that some kids were way more musically adept than others, especially our group, but the stakes were raised when word got out that this upperclassman, Chris, was going to play a school assembly with his brother and some other friends. I had no idea this loner kid with stringy blond hair and an all-season army jacket could talk let alone sing and play guitar. I never saw Chris in the middle of any social circle, not even the stoner crowd, who admired him from afar, as he stood alone under a tree and read a book or just gazed into the distance.

“Wait ‘til you see his band,” one of my burnout friends raved. “They’re amazing!”

“What kind of music do they play?”

“Southern Rock: the Allmans, Skynyrd, some Stones…”

I couldn’t get over the fact that Chris was capable of making a peep. His bandmates didn’t go to our school. I looked down at Southern Rock, thinking it was dumb, beer-drinking music — way beneath me. Only Ted Nugent was dumber than Lynyrd Skynyrd. I knew that the Allmans were supposed to be the Thinking Man’s Southern Rock band, but thanks to my Yankee prejudices, that struck me as highly relative notion.

“What’s the name of their band,” I asked.

“Syd,” came my friend’s reply, followed by a disturbing “uh, heh-heh” chuckle that I first heard from FM radio-loving upperclassmen a couple years earlier. “They spell it S-Y-D,” and again he made that knowing chuckle. The name, he explained, was theorized to be both a reference to Pink Floyd’s original leader, Syd Barrett, as well as, as my friend put it, “a shorthand for ‘acid.’ Get it?”

“Mmm…”

The next day we gathered in the old auditorium to witness what would be for me, at least, the first audible sounds by our schoolmate. Just like the Allman Brothers, Chris played lead guitar while his brother played a Hammond B3 organ. There was a second guitarist, a bassist, and a drummer. These guys had professional gear up to the gills: Gibson SGs, big tube amps… They had long hair and dressed like Neil Young. As advertised, they played a mix of Allman Brothers, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and Rolling Stones (“Brown Sugar”). They ended their set with a song I’d found excruciating whenever it came on the radio, “Whipping Post.” The song’s fatalistic blues-tradition lyrics, like “I drown myself in sorrow/As I look at what you’ve done/Nothin’ seems to change/Bad times stay the same/And I can’t run,” drove me bonkers. I wanted nothing to do with giving into the blues. I wanted a “white riot, a riot of my own,” as the Clash sang.

Watching “Whipping Post” played live, however, by Silent Chris and his band, it was actually thrilling. How did these kids generate so much noise while coordinating all those tricky blues licks? How did these skinny, northern white boys sing like barrel-chested southern sharecroppers? It was like the time my Dad took me to the Pocono 500 Indy car race as a kid. I had no interest in cars and auto racing beyond my Hot Wheels sets, but after 50 laps or so, I got carried away by the assault on the senses: the blur of the cars as they whizzed around the track, the deafening roar of the engines, and the asphyxiation from the thick exhaust that permeated the air.

Stories of the Allmans working out their parts permeate One Way Out. The dual drummers, Jaimo and Butch Trucks, talk about how they learned to play off each other’s strengths and styles. So much is made of Oakley’s distinctive bass style that I need to pull out my few Allman Brothers Band albums and see if I can learn to better appreciate the band through those bass parts, the way I learned to follow Phil Lesh’s loopy bass lines into a deeper appreciation of the Grateful Dead. Stories about how Dickey Betts and Duane found their parts eventually lead to a studio cat, Les Dudek, complaining about the lack of songwriting credit he received for helping to arrange the guitar harmonies in some famous mid-‘70s composition by Dickey. By this point, the story suggests, the Betts’ lead lines dictated the resulting harmonies. I could put my ears aside during the reading of this book and admire the maturity and commitment it took for the Allmans to persist as a band for all those years.

The band—and the book—drag on long past any musical relevance, but the story holds up on the dignity and strength of the revolving band members’ commitment to the founding members’ original vision. As third- and fourth-generation replacement members entered the narrative, I kept expecting the focus to lazily fall on the drug-and-alcohol excesses of Gregg Allman and Dickey Betts, as most rock biographies do once the music’s over. Betts, however, comes off like a consummate craftsman, despite occasional episodes of hell-raising and belligerence. Gregg ambles through One Way Out more of a ghost than his deceased brother, while replacement members like keyboardist Chuck Leavell and Warren Haynes take on responsibility for seeing through and building upon the band’s musical legacy. Haynes’ work in keeping the band alive is particularly heroic, so much so that I am curious to give his own torch-bearing jam band, Gov’t Mule, a listen, despite the fact that I never even dug peak-period Allmans

A large part of being in a band is feeling like you’re in a band, whether you’re the band’s leader, a founding member, or a fourth-generation replacement member. To be in a band is to feel like your music matters, no matter how “selective,” as Spinal Tap once put it, your audience gets. Did you know The Allmans have had a percussionist (Matt Quiñones) since 1991? These road warriors, well past their prime and already saddled with the expense of hauling equipment for two drummers, also carry a percussionist. Quiñones expresses pride in being a Brother longer than many of the band’s better-known members. Whatever Duane drove into those idealistic hippie kids in his half dozen years as a working musician ran deep.