THE ATLANTIC: In 2012, an officer was arrested for selling heroin; he was one of 40-some officers charged with corruption after the “Tainted Justice” investigation. That may be evidence that “Tainted Justice” sparked more oversight, but more likely it’s an indication that police corruption has continued with abandon despite it. Last year, Jeffrey Walker, another rogue narc-squad officer in West Philly, was charged with robbing drug dealers. He pleaded guilty and agreed to cooperate with prosecutors. Courthouse insiders say that Walker will finger as many as 15 dirty cops who are still on the streets. The city’s capacity for police corruption seems to be bottomless.

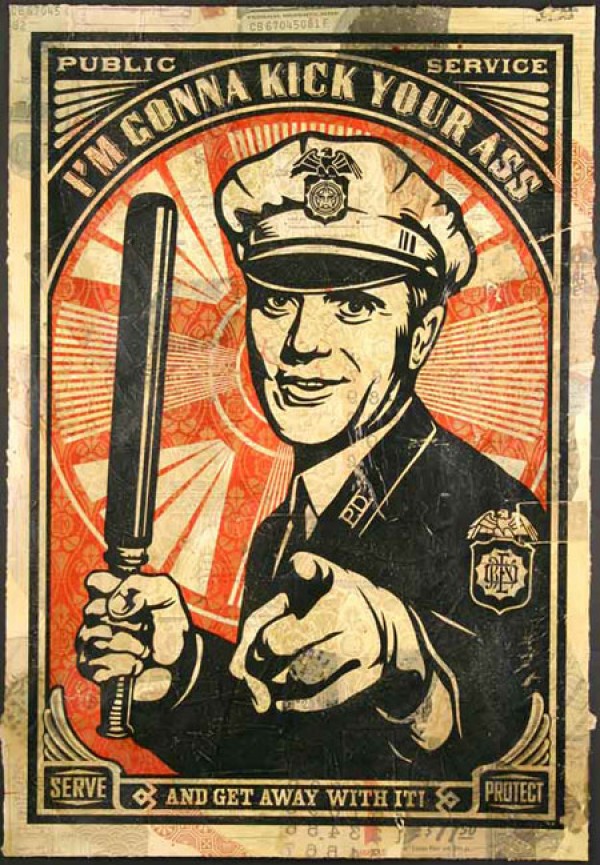

The root of police corruption, not just in Philadelphia but nationwide, is partly the war on drugs—a fact that the press, watchdog or not, often overlooks. The drug war has given the police carte  blanche to operate lawlessly in poor neighborhoods, where anyone who complains of ill treatment can be labeled a drug user or dealer whose word can’t be trusted. The cash-based black market for drugs makes it a ripe target for greedy cops who feel that their official compensation isn’t adequate for the risks they take. The morally questionable methods that cops adopt to make arrests, like recruiting drug addicts as paid confidential informants, create a situation where falling on the wrong side of the law can become commonplace for making big busts. When cops come to court with a weak case, they can commit perjury and the system will give them the benefit of the doubt.

blanche to operate lawlessly in poor neighborhoods, where anyone who complains of ill treatment can be labeled a drug user or dealer whose word can’t be trusted. The cash-based black market for drugs makes it a ripe target for greedy cops who feel that their official compensation isn’t adequate for the risks they take. The morally questionable methods that cops adopt to make arrests, like recruiting drug addicts as paid confidential informants, create a situation where falling on the wrong side of the law can become commonplace for making big busts. When cops come to court with a weak case, they can commit perjury and the system will give them the benefit of the doubt.

The problem can’t be solved internally. The local FOP resembles a mafia clan, complete with an omerta code and enormous influence over its particular sphere of local politics. Every officer knows that a rogue cop may get pulled off the street and stuck on desk work for a while—maybe he even loses his job—but the FOP wins nine out of 10 cases in arbitration. The drug war has created in police departments the same kind of monsters that the Catholic Church did during decades of covering up sexual abuse and reassigning accused priests to different parishes. Eventually the priesthood became a magnet for potential predators once it was abundantly clear that abusing children held no consequences. Likewise, Philadelphia’s police department attracts power-abusing would-be criminals seeking the cover of a badge. MORE

RELATED: There is a letdown at the end of the Busted narrative, but one that was out of the reporters’ hands: at the crucial last act of the investigation—accountability—there is, unfortunately, little to report. The City of Philadelphia has paid $2  million to settle 33 lawsuits filed by bodega owners and two of the victimized women. The FBI [has closed their case with no files charged against the officers]. None of the assaulted women have been interviewed by the FBI. José Duran, one of the bodega owners raided by the police, had a video of five cops cutting the surveillance camera wires at his shop. He has since lost his business and had to sell his home—a circumstance the reporters suggest is particularly unfair when the cops he caught on video remain working with the police department. Duran now rents a smaller space and works in the meat department of Costco. “It’s frustrating,” Ruderman said. “Especially with the women [who were assaulted by the police officers] … we just can’t understand why charges haven’t been brought and we can’t help but think that if these women were white and from the suburbs, they would be taken seriously.” MORE

million to settle 33 lawsuits filed by bodega owners and two of the victimized women. The FBI [has closed their case with no files charged against the officers]. None of the assaulted women have been interviewed by the FBI. José Duran, one of the bodega owners raided by the police, had a video of five cops cutting the surveillance camera wires at his shop. He has since lost his business and had to sell his home—a circumstance the reporters suggest is particularly unfair when the cops he caught on video remain working with the police department. Duran now rents a smaller space and works in the meat department of Costco. “It’s frustrating,” Ruderman said. “Especially with the women [who were assaulted by the police officers] … we just can’t understand why charges haven’t been brought and we can’t help but think that if these women were white and from the suburbs, they would be taken seriously.” MORE