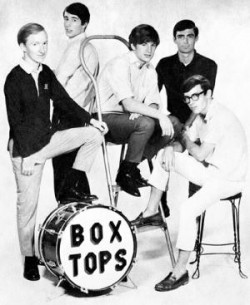

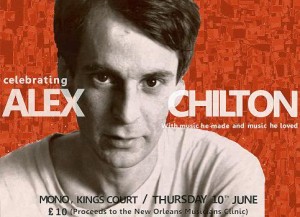

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Alex Chilton remains a forbidding totem of American music with a formidable pedigree: white soul prodigy, progenitor of power-pop purity, pill-addled punk, swampy garage blooze and, in the final decades of his life, indie’s aging princeling of noble white failure. He was a musician’s musician, and each entry on his resume has spun off countless imitators and innovators. Forever to be known as the guiding light in Big Star’s twinkling constellation of pure pop, Alex Chilton would probably have it any other way. Even during the reunion/reactivation of Big Star in the last two decades of his life, Chilton seemed reluctant to give power-pop fetishists what they craved so hungrily: more of the same. The irascible, iconoclastic singer/songwriter cipher, who died from a heart attack in 2010, spent nearly the entirety of his 45-year career confounding people’s expectations, including his own. Nobody figured a 16-year-old white kid could sing with the swampy frogman growl he wielded during his tenure with the Box Tops in the ’60s. Big Star’s feathery weave of the Beatles and the Byrds was hardly par for the course in the shaggy dog days of the early ’70s, which, in part, explains why the band never really sold any records before disbanding. And from the late ’70s onward, his solo career zigged, sometimes brilliantly, when his audience seemed to zag. In the ’90s he pretty much dispensed with songwriting altogether, settling into the role of semi-ironic interpreter of obscure soul, R&B, jazz and Italian rock ‘n’ roll nuggets.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Alex Chilton remains a forbidding totem of American music with a formidable pedigree: white soul prodigy, progenitor of power-pop purity, pill-addled punk, swampy garage blooze and, in the final decades of his life, indie’s aging princeling of noble white failure. He was a musician’s musician, and each entry on his resume has spun off countless imitators and innovators. Forever to be known as the guiding light in Big Star’s twinkling constellation of pure pop, Alex Chilton would probably have it any other way. Even during the reunion/reactivation of Big Star in the last two decades of his life, Chilton seemed reluctant to give power-pop fetishists what they craved so hungrily: more of the same. The irascible, iconoclastic singer/songwriter cipher, who died from a heart attack in 2010, spent nearly the entirety of his 45-year career confounding people’s expectations, including his own. Nobody figured a 16-year-old white kid could sing with the swampy frogman growl he wielded during his tenure with the Box Tops in the ’60s. Big Star’s feathery weave of the Beatles and the Byrds was hardly par for the course in the shaggy dog days of the early ’70s, which, in part, explains why the band never really sold any records before disbanding. And from the late ’70s onward, his solo career zigged, sometimes brilliantly, when his audience seemed to zag. In the ’90s he pretty much dispensed with songwriting altogether, settling into the role of semi-ironic interpreter of obscure soul, R&B, jazz and Italian rock ‘n’ roll nuggets.

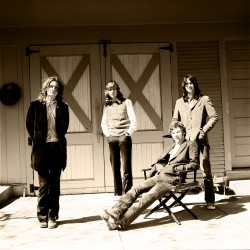

It has been said that the genre of power pop -– frail, white man-boys with cherry guitars reinvigorating the harmonic convergence of the Beatles, the Beach Boys and the Byrds with the caffeinated rush of youth –- is the revenge of the nerds. Big Star pretty much invented the form, which explains the worshipful altars erected to the band in the bedrooms of lonely, disenfranchised melody-makers from Los Angeles to London and points in between. Though they never came close to fame or fortune in their time, the band continues to hold a sacred place in the cosmology of pure pop, a glittering constellation that remains invisible to the naked mainstream eye. Succeeding generations of pop philosophers and aspiring rock Mozarts pore over the group’s  music like biblical scholars hunched over the Dead Sea Scrolls, plumbing the depths of the band’s shadowy history, searching for meaning in Big Star’s immaculate conception and stillborn death. Big Star was the sound of four Memphis boys caught in the vortex of a time warp, reinterpreting the jangling, three-minute Brit-pop odes to love, youth and the loss of both that framed their formative years, the mid-’60s. Just one problem: It was the early ’70s. They were out of fashion and out of time. Within the band, this disconnect with the pop marketplace would lead to bitter disillusionment, self-destruction and death. But that same damning obscurity would nurture their mythology and become Big Star’s greatest ally, an amber that would preserve the band’s three full-length albums -– #1 Record, Radio City and Sister Lovers/Third –- as perfect specimens of neo-classic guitar pop. That Big Star’s recorded legacy would go on to inspire countless alternative acts is one of pop history’s cruelest ironies –- everyone from R.E.M. to the Replacements to Elliott Smith to Wilco would come to see Big Star as the great missing link between the ’60s and the ’70s and beyond.

music like biblical scholars hunched over the Dead Sea Scrolls, plumbing the depths of the band’s shadowy history, searching for meaning in Big Star’s immaculate conception and stillborn death. Big Star was the sound of four Memphis boys caught in the vortex of a time warp, reinterpreting the jangling, three-minute Brit-pop odes to love, youth and the loss of both that framed their formative years, the mid-’60s. Just one problem: It was the early ’70s. They were out of fashion and out of time. Within the band, this disconnect with the pop marketplace would lead to bitter disillusionment, self-destruction and death. But that same damning obscurity would nurture their mythology and become Big Star’s greatest ally, an amber that would preserve the band’s three full-length albums -– #1 Record, Radio City and Sister Lovers/Third –- as perfect specimens of neo-classic guitar pop. That Big Star’s recorded legacy would go on to inspire countless alternative acts is one of pop history’s cruelest ironies –- everyone from R.E.M. to the Replacements to Elliott Smith to Wilco would come to see Big Star as the great missing link between the ’60s and the ’70s and beyond.

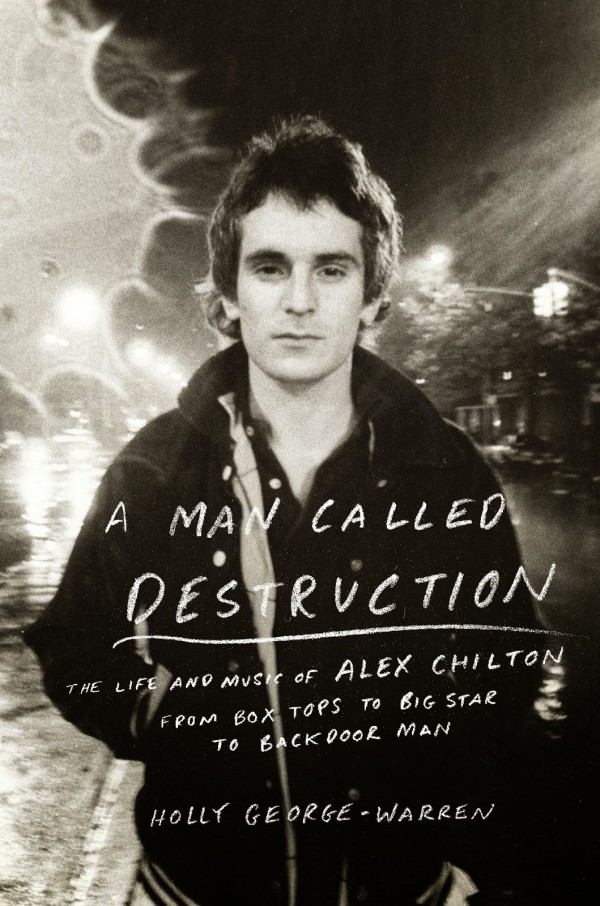

All of which makes veteran music journalist Holly George-Warren [PICTURED, BELOW RIGHT]’s comprehensive, just-published Chilton biography, A Man Called Destruction, essential reading for anyone hungering for knowledge of the secret history of unpopular music. George-Warren’s bibliography is impressive: Public Cowboy No. 1: The Life and Times of Gene Autry (Oxford University Press, 2007), The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: The First 25 Years (HarperCollins, Sept. 2009), Bonnaroo: What, Which, This, That, the Other (Abrams Image, 2012), Cowboy! How Hollywood Invented the Wild West (Readers Digest Books, 2002), Punk 365 (Abrams, 2007), Grateful Dead 365 (Abrams, 2008); and the children’s books Honky-Tonk Heroes and Hillbilly Angels: The Pioneers of Country & Western Music (Houghton Mifflin, 2006), Shake, Rattle & Roll: The Founders of Rock & Roll (Houghton Mifflin, 2001), and The Cowgirl Way (Houghton Mifflin, July 2010). Recently, we got her on the horn to talk about all things Alex Chilton. Full disclosure: George-Warren used interviews I conducted with Chilton back in 2000 as source material for her book.

PHAWKER: First question, how did you discover Alex Chilton’s music?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Wow. Well, way back when — when I was just a wee lass in North Carolina — I happened to go to college and hang out on the scene with some people from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, who had discovered Alex — you know, Big Star actually — as it happened, as the music came out. So, I was first exposed to Big Star music somewhere in there. It’s a little foggy in my adult brain exactly when, but somewhere there in the late 70’s through the connection of people –many of whom became members of the dBs. And you know, I didn’t start putting two and two together that this was the guy from The Box Tops. And as a kid, growing up, buying records, buying 45’s — you know, beginning in third grade — I loved The Box Tops, and I bought their records. In fact, the first one I bought was “Sweet Cream Ladies, Forward March,” which actually got airplay on an Asheboro radio station because that’s how I would’ve heard it. I found out, while doing research for the book, it was banned in some market because it’s subject matter being — you know– ladies of the night. So, that’s kind of how I first discovered music. Then back in 1982, when I was traveling around the country — I wrote this in the epilogue of the book– I actually got introduced to Alex for the first time by a dear friend I was traveling with, who sadly, in a weird twist of fate, passed away last week. That’s my sadness. We were traveling together and she met Alex because she had been a former girlfriend of Peter Holsapple, of the aforementioned Winston-Salem posse, and had met Alex when the two of them lived in Memphis in ‘78. So, we ran into him on the streets of New Orleans. That’s actually when I first met the guy.

PHAWKER: And tell me about your relationship with him over the years.

PHAWKER: And tell me about your relationship with him over the years.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: When he came back and started playing again with his trio, he showed up, playing in the New York area where I then lived, and I immediately wanted to see him play. The first gig of his I ever saw was in 1984 at Maxwell’s in Hoboken, and at that time I had this wacky little band called Clambake. And not even putting two and two together that we were named after an Elvis movie — Alex being from Memphis and all — but my combo had this little, tiny deal with an indie label, and the owner said ‘Get a producer.’ I suggested Alex because of his working with the Cramps, and I was a huge Cramps fan. So, sure enough, I go clomping down the steps at Maxwell’s saying ‘I don’t know if you remember me’, and he immediately remembered my birthday was on October 10, from having met two years before, and agreed to produce my combo’s little EP for $500 and a lamb chop dinner. So, that’s how I got back into his orbit a little bit. Being a fan, I went to all the shows pretty much that he played in New York, and in ‘85, he produced our record, and he actually crashed — my boyfriend and I had a place on St.Mark’s place. He crashed there, and I indeed cooked him lamb chops myself — first time I ever cooked that. I guess it was good enough because he did produce the record. So, that kind of made it so we knew each other better and better, and we also did a gig with him, which I also write about in the book, in the epilogue. We opened up for him at this cool little club in the Village. So, he was the kind of guy that could be very friendly and very interested in other people and what they were doing. So, he would often call when he was in New York. We’d hang out. End up cruising around in his big ol’ car. It was crazy, you know? He was up for doing stuff sometimes into the 80’s and 90’s. So, just getting to spend time with him, I knew him more as an acquaintance that we just talked about music and books and pop culture stuff — never about personal life kinds of stuff. So, doing the research in the book, it was hugely eye-opening. I had no idea of the tragedy he’d experienced in his life. He was very private, and never spoke about it.

PHAWKER: What’s some of the tragedy that you’re referring to?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Oh, you know, just about his brother dying when he was really young. You know, his brother died when he was six.

PHAWKER: Drowned in the tub, right?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Yeah. Drowned in the bathtub, after having a seizure. And, you know, you just don’t think about what someone goes through, thrown out into to the world as a big pop star with no kind of security, kind of support systems really, to kind of walk him through that kind of whirlwind that he went through. The effect that had, and of course, the whole thing with Big Star, being so into making that music and it being a complete flop, and of course the death of Chris Bell, which was such a tragedy, and I think had a much greater effect on him than he led on. And you know, just feeling disconnected from people due to his own — I think he was up and down with his moods and stuff like that. Just dealing with all the stuff that happened. He had a very turbulent love life.

PHAWKER: You think if he would’ve been born 20 or 30 year later, he would’ve been on antidepressants or something like that? Perhaps diagnosed as bi-polar?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Well, it’s interesting, Jonathan, because I have to say it was so amazingly eye-opening too, listening to that interview you did with him in 2000. That was just — that was to me one of the biggest things to hear because he  seemed very alienated and isolated in that interview. He seemed to be very alone and worried about the future, and you know, lonely, and all that kind of stuff. And he also –still the fact that he was so dependent on astrology, and also how much he talked about his interest in psychology Wilhelm Reich. He got very much caught up in reading Reich and other psychological studies like Carl Jung in the mid-70’s. He really used that as a tool to help him cope with the depression that he had undergone after everything shook out with Big Star, break ups with Lesa, his girlfriend. All the commercial failure, all those disappointments with his career. He really turned to reading a lot of psychology.

seemed very alienated and isolated in that interview. He seemed to be very alone and worried about the future, and you know, lonely, and all that kind of stuff. And he also –still the fact that he was so dependent on astrology, and also how much he talked about his interest in psychology Wilhelm Reich. He got very much caught up in reading Reich and other psychological studies like Carl Jung in the mid-70’s. He really used that as a tool to help him cope with the depression that he had undergone after everything shook out with Big Star, break ups with Lesa, his girlfriend. All the commercial failure, all those disappointments with his career. He really turned to reading a lot of psychology.

And also in that interview that you did, there was this interesting thing, he was remembering to you about this college professor [he had]. He very briefly went to college in Memphis, and during the Big Star period, he was really talking about his philosophy professor then. All that is to say that he was interested in psychology, and I think he was using that and astrology as a tool to help understand others and himself. He was also clearly one of those people, like many of us, who self-medicated over the years when necessary through drugs, alcohol, weed, you know, etc. So, would he have gone on medication? That is really hard to hypothesize, and always very nervous to try to do that, but I guess I can say there was a chance he would’ve done that.

PHAWKER: You mentioned his astrology thing, and that was something that surprised me when I did that interview. I don’t know if it is on the tape, or we talk about it. He did a whole reading on me. I just found that very curious, because I just saw him as such a sardonic and skeptical person, and he was all in on astrology.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Yeah. Well, he really treated it like a science. To him, it wasn’t some kind of New-Agey hippy thing, even though he got into it in the late ’60’s. But he really studied it as a science, and read some very esoteric texts. Got really deep into it, and really as a gift to friends and journalists — including myself — he would do readings, and I’ll tell you Jonathan, I did the same freaking thing you did, because he gave me a reading as well in 1991 and I still have my notes on my legal pad, all these notes I jotted down. He did it over the phone to me, did the reading on the phone, and like a freaking idiot, I didn’t tape that, even though I just taped an interview with him. And you did the same thing. You asked him a few questions about it, he didn’t do the reading out loud. It wasn’t on your tape.

PHAWKER: Ah.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: But you responded and said ‘Oh, blah blah blah’ — whatever. Pulled out a few things. I was so struck by what he said to you about astrology. You know, he took it very seriously, and it also gave me the realization that sometimes when he would turn a journalist down, it wasn’t just because he was being a difficult, he was being kind of guided, you know. A lot of people thought he was so changeable. Like one day he would do something, the next day it would be a totally different story. And in your conversation with him, I believe that he actually consulted his charts and that would help him decide whether or not to give an interview. It wasn’t that he was being mercurial. Poor Barney Hoskyns, this incredible, very professional with a lot of credits journalist, just tried a year to get an interview with Alex for this big piece he did for MOJO, and he finally got Alex on the phone and Alex just absolutely refused.

PHAWKER: Really?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: He wouldn’t do the interview.

PHAWKER: I think that was right around the same time I did mine.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Yeah. It was just a few months before your interview. In your interview, he talked about a certain period he was entering according to his charts. So, you lucked out. You were in the right period to get the interview. Poor Barney, he didn’t.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Yeah. It was just a few months before your interview. In your interview, he talked about a certain period he was entering according to his charts. So, you lucked out. You were in the right period to get the interview. Poor Barney, he didn’t.

PHAWKER: But why do you think of all the things he dismissed or didn’t believe in, including — I think he was an atheist, although you can correct me on that if you know otherwise– but I mean, why is it of all the things he would roll his eyes at, that he would embrace astrology. I don’t mean to be dismissive, and not that I know that much about astrology beyond it being a back of the National Enquirer kind of thing — but of all the belief systems that you could embrace, I would think that would be way down the list of credible things for a guy like him.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Well, I think for serious students of astrology, I think there could be something to it, and I think that he was a deep enough student of it that he could have waded back to the ancient history and all that kind of stuff. All the different cultures. He was a student of Chinese astrology, all these different kinds of astrologies. So for him, I think there is a kind of pop component to any kind of theory or spiritual practice, you know? I mean, look at Jesus Christ Superstar in Christianity, you know? So yeah, there’s definitely like a real pop element and New Age element to astrology that you can kind of poke fun at but I think for people that dig deep and pursue it as a scholarly pursuit, I think there’s just as much plausibility in that deep belief system as there is in mainstream religion, you know? And I really think Alex was a seeker. He grew up — yes, his parent were atheists– but the kids went to the Episcopal church where his brother was an altar boy. His sister, maybe in a way to get away from the grief of the brother’s death, became a christian, and pursued that when she was in high school. Alex — again, thanks to your interview, Jonathan — he actually admitted to briefly looking into Christianity when all those other guys in Memphis became born-again. Chris Bell, John Fry, and all those other people. He did look into that a little bit. For whatever reason, he scoffed at that, and it may have been that Groucho Marx thing, ‘I don’t want to be part of a club that would have me.’ And maybe the astrology thing, because it can be a very solitary pursuit of understanding the universe, all of that, maybe that appealed to him more than some kind of communal belief system. Again, I really hesitate to hypothesize too much, and I try not to do that too much in the book. A lot of people play armchair psychologist when they write biographies, and it is tempting to do that, and you can put a lot of things together and draw conclusions, but — especially with Alex, I had little trepidation about doing that.

PHAWKER: Understandable. And in fairness to astrology, and people who follow that out there, if the moon can affect the tides, then the orbits and the stars and the planets certainly could have some influence on phenomenon in the universe.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Hey listen, if you’ve never been a chick and been on a menstrual cycle that’s callibrated by the moon, and been in a all-girl band where suddenly things start happening, your cycles start lining up. There’s stuff we don’t understand. So, that’s a big mystery.

PHAWKER: More things in heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in our freshman syllabus, right?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Oh, yeah. Definitely. And I have to confess that I really intended to come as a scholar of astrology during the research of my book. I do think that understanding it better that maybe I could understand Alex better. It takes years of research and study to understand some of that stuff. It’s really esoteric shit. I studied as much as I could and hope that I will have time in my retirement to study it more and see if I believe in it or not.

PHAWKER: What was the lightbulb-moment when you decided ‘I’m going to write the biography of Alex Chilton’?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: I was at South by Southwest, and I had found out that Alex had died, and I was just wiped out with grief. I had been meaning to call Alex to see if he could hook up as soon as I found out he was going to be down there,  and I finally — being a horrible procrastinator — I finally called him on his cell phone the day he died. I kept getting this weird busy signal, and it was like a peculiar busy signal, and to this day, I don’t know what that was about, but I just thought maybe he turned off his cell phone. Maybe he didn’t want to be bothered by people. Later that afternoon, I was in a little shuttle van, and this guy next to me is chatting on his phone and was suddenly like ‘What?!? No! You’ve got to be kidding! No! When did it happen?!?’ The hung up, and in this Memphis accent said ‘I’m sorry ya’ll, but I’m just so upset that we just lost another great Memphis musician. Alex Chilton just passed away.’ And I was like ‘What?’ And this guy was from like the Memphis Music Board or something, so I just freaked out. I was really upset, and then I thought, well maybe Alex is faking it so he doesn’t have to go to South By or something, you know? But the truth became the truth, and I was just devastated on the phone with my agent — an amazing woman, and a big big music fan herself. She had actually gone to see Alex Chilton and Big Star gigs with me over the years. She knew I was crazy about Alex’s music. In fact, when Alex wanted to write a book with me back in the early 90’s, you know, I had mentioned it to her. So she’s the one who suggested ‘Holly, you’ve got to write a biography about Alex’ because I had done some other books after my Gene Autry biography, but I had not written another, you know, biography. So she really convinced me to do it. She checked around with some major publishers in New York, to see if they’d be interested in my doing one, and 11 publishers said yes they would love to read a book proposal on a book about Alex, and of those 11, five made offers to publish the book.

and I finally — being a horrible procrastinator — I finally called him on his cell phone the day he died. I kept getting this weird busy signal, and it was like a peculiar busy signal, and to this day, I don’t know what that was about, but I just thought maybe he turned off his cell phone. Maybe he didn’t want to be bothered by people. Later that afternoon, I was in a little shuttle van, and this guy next to me is chatting on his phone and was suddenly like ‘What?!? No! You’ve got to be kidding! No! When did it happen?!?’ The hung up, and in this Memphis accent said ‘I’m sorry ya’ll, but I’m just so upset that we just lost another great Memphis musician. Alex Chilton just passed away.’ And I was like ‘What?’ And this guy was from like the Memphis Music Board or something, so I just freaked out. I was really upset, and then I thought, well maybe Alex is faking it so he doesn’t have to go to South By or something, you know? But the truth became the truth, and I was just devastated on the phone with my agent — an amazing woman, and a big big music fan herself. She had actually gone to see Alex Chilton and Big Star gigs with me over the years. She knew I was crazy about Alex’s music. In fact, when Alex wanted to write a book with me back in the early 90’s, you know, I had mentioned it to her. So she’s the one who suggested ‘Holly, you’ve got to write a biography about Alex’ because I had done some other books after my Gene Autry biography, but I had not written another, you know, biography. So she really convinced me to do it. She checked around with some major publishers in New York, to see if they’d be interested in my doing one, and 11 publishers said yes they would love to read a book proposal on a book about Alex, and of those 11, five made offers to publish the book.

PHAWKER: In the book you dispelled the legend, oft repeated by [legendary Big Star producer] Jim Dickinson, that the famous Memphis photographer Williams Eggleston lived next door to the Chiltons, and when he was growing up Alex spent a lot of time hanging out with Eggleston in the dark room. And as the story goes, one day Eggleston gave Alex a hit of LSD when he was something like 10 years old, just a little kid.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Well Jim’s claimed that Eggleston gave him peyote or something like that, but I don’t really think that happened because, basically, Eggleston, if you look at the timeline, and I interviewed Eggleston’s wife Rosa, who had a pretty good memory, just the timeline of when they got married and when they started hanging out with the Chiltons. And by that time, Alex was older than what Jim had said, and I don’t know, Eggleston at that point and time, that was before he started really hanging out with a video camera, and filming, and doing the drug thing. He was much more of a imbiber at that point. Jim was a walking encyclopedia of knowledge and an amazing storyteller. I would say among the top five best storytellers that I’ve ever interviewed in my illustrious career, but he also — being from the south, as am I — he never let the truth get in the way of a good story. He was kind of — believe me, you know how it is Jon– I found out myself. Whenever you write a biography, there’s a real rashomon quality that happens. I interviewed three people that were in the same room at the same time, and all three tell a different story about exactly what happened. So, people’s memories, it’s just human nature, if they get screwed up from all the passage of time, substances, or whatever. So, I’m sure he thought that was the case, but it was not.

PHAWKER: Let’s go back to the Box Tops here. Alex, in a lot of ways, suffered from child star syndrome.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Oh, totally. Completely. Yeah.

PHAWKER: It was pretty much all over for him by the time he could vote, and he went from being an international pop star with the number one record in America to can’t get arrested when he’s 19 years old.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: He had the great trappings of stardom and was just thrown out in this whirlwind when he hadn’t really grown up yet. Being a mother of a 16 year old kid myself, when I think about the effect it would’ve had on my son with the same sort of thing happening to him, and there’s no guidance or any kind of support system or anything, it’s a recipe for disaster. And you see what happens to so many of these child stars. You definitely saw that coming out in Alex, I think.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: He had the great trappings of stardom and was just thrown out in this whirlwind when he hadn’t really grown up yet. Being a mother of a 16 year old kid myself, when I think about the effect it would’ve had on my son with the same sort of thing happening to him, and there’s no guidance or any kind of support system or anything, it’s a recipe for disaster. And you see what happens to so many of these child stars. You definitely saw that coming out in Alex, I think.

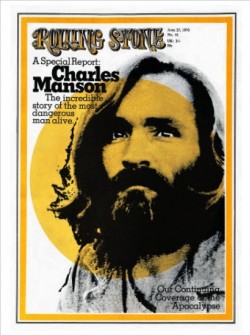

PHAWKER: Let’s talk about the time Alex Chilton met Charlie Manson.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Okay. Well, Alex became very close friends with the Beach Boys, doing many gigs with them while he was with The Box Tops, and the summer of ‘68, following a tour, he was invited out to California, to Malibu, to stay with Dennis Wilson at his house. And it just so happened that Wilson had this kind of entourage of hangers-on, as rock stars were wont to do in those days, and picked up a girl hitchhiking, who happened to be a member of the Manson family. So next thing you know, Charles Manson and a bunch of the followers had moved in. And this happens while Alex was there. Manson already had this colder personality, and kind of had these women to do his bidding. At first Alex was like ‘Ooo, look at these chicks in no underwear! Hey!,’ you know? And basically, he later said they wouldn’t pay that much attention to him because Charlie wouldn’t let them. The big incident occurred when he was walking down the hill to get some groceries. You know, they were up on this mountainside. He schlepped down the hill to buy some groceries. He was going to pay for it all himself, and one of the girls said ‘Oh, Charlie’ — apparently the Manson people lived off cereal. They loved eating breakfast cereal. And I don’t know which kind. I wish I knew if it was Trix or Count Chocula, Lucky Charms or whatever. Could you imagine that?

PHAWKER: Cukoo Puffs would be my guess.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Anyway, they sent him off and he was supposed to bring two gallons of milk. Well, knowing Alex, because he was a rock star — come on. To schlep all these heavy groceries, including two gallons of milk, up this mountainside path? So he decided not to buy the milk because he didn’t want to schlep it, and when he got back, they were like ‘Where’s the milk? He didn’t buy the milk? Charlie’s going to be very very angry.’ They were kind of blocking him at the door, wouldn’t let him in unless he got the milk, and gave him the scary stare treatment. And then things really took a scary turn. After a night of partying at the house, he woke up the next morning on one of those big sectional couches or something like that, and asleep next to him was Charlie Manson. He was like ‘Um, I really want to get out of this place.’ So, he left soon after that. So it was like a year later, Alex’s in England, after an aborted tour, kind of stranded in London for a while, and they were walking down the street and saw a tabloid with the picture of Charlie on the cover saying ‘Suspect Arrested In Tate Slayings’ and he just completely freaked out he they saw it. I think it really scared him. Even when he told that story later, he was kind of weird and hesitant about it when he talked about it to the press, but the funny thing is, when he asked me to write a book with him, kind of a memoir of his years on the road with The Box Tops and everything, he said he wanted to name it ‘I Slept With Charlie Manson.’

PHAWKER: Moving onto Big Star. Let’s start with: What is your favorite Big Star Album?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Oh, god. That’s such a hard question because I went through my periods of being obsessed with each of the three. But, if I had to do the desert island thing, I guess I would go with Third.

PHAWKER: So you do think of Third as a Big Star record as opposed to a Alex Chilton solo record?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: It’s always been called a Big Star album, and [Big Star drummer] Jody Stephens is on the record, wrote one of the songs, and at the time it was done with — I guess in reality it was an Alex solo album, but it seems like — I don’t know. I don’t really have an answer. It’s a hybrid. It’s a hybrid Big Star/Alex Chilton solo album.

PHAWKER: Explain the dynamic between Alex Chilton and Chris Bell’s relationship, and how that impacted the course of the band’s history

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Alex always said the first album, #1 Record, was his favorite of the Big Star albums, that it was a really exciting experience for the two of them to find each other and work together. Because I think as much as Alex would late cringe to being compared to Lennon-McCartney, I think there was definitely that kind of working environment. Each guy had already written songs and brought them into the studio or to key production sessions and the other guys complimented the  other’s work and added his own sensibility to it, music ideas, and really made it even better. You know, Alex’s songs that he had written in New York as pretty much singer songwriter folky-type things on a acoustic guitar. Chris added more complicated guitar parts and layering sound, and all that type of stuff. So, I think in the beginning, it was just a exhilarating, complimentary experience. But as it so often happens with two great artist working together, other elements that come into play take a really horrible toll on those relationships. Jealousy, competition. I think from the beginning it was always a competition, and that can spur great work, and I think in the beginning, they had such admiration for one another. Chris really admired Alex’s voice, and liked his songs. Alex really admired Chris’ guitar playing, and like his songs. So, in the beginning, it was definitely a mutual admiration, the whole inter-workings of what happens with a band. All those taking sides and alliances, and those kinds of things that come into play, and of course when Alex was starting to get name-checked in all the reviews, and Chris started getting really really jealous. Both guys weren’t the most stable guys in the world. They were all still quite young They both had a lot of baggage that they brought in as people. Of course that’s going to make things even more difficult to handle emotionally. Then the first album totally bombed due to the lack of support from the label and the distribution problems. And on top of everything, the chemical indulgences that destroyed everything and made everything worse. So there you go. A perfect recipe for, you know, a one-album collaboration, sadly.

other’s work and added his own sensibility to it, music ideas, and really made it even better. You know, Alex’s songs that he had written in New York as pretty much singer songwriter folky-type things on a acoustic guitar. Chris added more complicated guitar parts and layering sound, and all that type of stuff. So, I think in the beginning, it was just a exhilarating, complimentary experience. But as it so often happens with two great artist working together, other elements that come into play take a really horrible toll on those relationships. Jealousy, competition. I think from the beginning it was always a competition, and that can spur great work, and I think in the beginning, they had such admiration for one another. Chris really admired Alex’s voice, and liked his songs. Alex really admired Chris’ guitar playing, and like his songs. So, in the beginning, it was definitely a mutual admiration, the whole inter-workings of what happens with a band. All those taking sides and alliances, and those kinds of things that come into play, and of course when Alex was starting to get name-checked in all the reviews, and Chris started getting really really jealous. Both guys weren’t the most stable guys in the world. They were all still quite young They both had a lot of baggage that they brought in as people. Of course that’s going to make things even more difficult to handle emotionally. Then the first album totally bombed due to the lack of support from the label and the distribution problems. And on top of everything, the chemical indulgences that destroyed everything and made everything worse. So there you go. A perfect recipe for, you know, a one-album collaboration, sadly.

PHAWKER: Why do you think their music never connected with a mass audience, as catchy as it was?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Well I think just lack of exposure, I think was the number one reason because the critics certainly loved it. All three of those records have a real timeless quality. They didn’t really fit into their time. But now listening to them, there’s a timelessness to their songs. Just look at the way they have affected generation after generation. Back in January, my son had a 16th birthday party here at my house, and it was packed with teenagers. By the end of the party, there was about 16 or so crammed into the parlor of the victorian house, one of the kids had an acoustic guitar — and these kids were around my sons age, anywhere from around 14-17 — and all of the sudden this kid is playing “Thirteen” on the guitar, while all the kids — boys and girls– start singing the song Thirteen. I’m like ‘What?!?’ I was just blown away, and my son didn’t even instigate it. My son loves the song, but these kids, you know, I think the other kids originally learned it from Elliott Smith. Because he’s kind of — you know how every generation has a martyred musician figure. For the new generation, it’s Elliott Smith.

Alex actually quipped about Big Star’s music and said if it had been popular back in the day, maybe people would’ve forgotten about it, like they did the Raspberries. They would’ve had the hit, but maybe they wouldn’t have had the longevity that they had because that cult status adds to the timelessness. Look at Nick Drake for example, from around the same time period. They weren’t overplayed back in the day. They’re still not in that 70’s oldies radio station loop, so people don’t get sick of it. It still sounds fresh. It still sounds new, and generations of new kids love it when they hear it. I teach college classes, and every year it’s always one or two kids who have heard of Big Star or Alex Chilton thanks to either The Replacements’ song “Alex Chilton,” or Elliott Smith, or whatever. They take this journey of discovery, and that’s very meaningful for people, as you well know. It was for me when I first heard Big Star. Back in those days, I was traveling to country, looking for used records stores, trying to find the Big Star records among other really hard to find vinyl. That made them even more precious.

PHAWKER: Alex is kind of the Zelig of rock n roll from the ’60’s onward. He was a player in ’60s pop and psychedelia, the early ’70s singer songwriter movement, early ’70s AM radio pop, punk rock, new wave, and then he became a cult hero to alternative/indie rock. Most people would be lucky to be in the middle of any one of those movements or moments — and he was in the middle of all of them.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Hey, listen. The guy shared the stage at the Grand Ole Opry with Tammy Wynette when “Stand By Your Man” was just coming out. I mean, it’s unbelievable all the stuff he experienced and witnessed in his career, and he was so quiet about a lot of it. He never bragged about any of his achievements or was all ‘I was there’ or anything like that. I mean, he could’ve easily cashed in on the whole Big Star craze in the 90’s once they did the reunion, but he couldn’t fake it. He really could not fake it. He told me that in an interview, ‘Look, I understand people come out to my shows and want to hear certain songs, and I want people to get their money’s worth, but I want to play what I want to play,’ You know, that’s how he was. Same thing about making records. He was a realist. He knew once you’re on a major label, you sort of sell your soul to the devil, you know? You kind of have to take marching orders, follow the party line and record the stuff they want, or they’re not going to put it out. Or if they do an it’s considered a big flop and failure, they’re going to own all the rights to it and you’re not going to get it back. So he just kind of wised up, and again set the template for pretty much what the music business is today by getting enough money from a label to cut the record, license the masters for just that one time use to different labels to put it out, and then he would own the masters.

PHAWKER: Smart move. Very smart move. Don’t you think that his relationship with longtime on-and-off girlfriend Lesa Aldridge — as toxic as their relationship was at time, according most accounts — was the great love of his life and he never quite got over her?

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: I think Lesa was the great muse of his life, and unfortunately, I think he was just at a place where he was unable to be in a relationship that wasn’t as troubled as that one was. And I mean with that being said, I think he always — again, I hate to hypothesize. I’m always nervous about that, because Alex never even mentioned her name to me, ever, and I’m sure he did to many other people. In fact, this is not in the book, but one of his close friends actually told me that as late as I believe the late 90’s or the early Aughts, he actually wrote an essay about Lesa, and read it to the friend over the phone. I would’ve given anything to get my hands on that. But I think she definitely never left his thoughts. She made a huge impact on him, and there was emotional baggage from that that he carried with him.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: I think Lesa was the great muse of his life, and unfortunately, I think he was just at a place where he was unable to be in a relationship that wasn’t as troubled as that one was. And I mean with that being said, I think he always — again, I hate to hypothesize. I’m always nervous about that, because Alex never even mentioned her name to me, ever, and I’m sure he did to many other people. In fact, this is not in the book, but one of his close friends actually told me that as late as I believe the late 90’s or the early Aughts, he actually wrote an essay about Lesa, and read it to the friend over the phone. I would’ve given anything to get my hands on that. But I think she definitely never left his thoughts. She made a huge impact on him, and there was emotional baggage from that that he carried with him.

PHAWKER: Forever.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: There’s a thin line between love and hate, as they say.

PHAWKER: Yeah. Well they were definitely stomping on that thin line.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: And it’s very poignant, interviewing Lesa because I know she still holds a torch for Alex.

PHAWKER: According to your book, Alex Chilton’s last words were ‘Run the red light!’ I had not heard that before. He was dying of a heart attack, being raced to the hospital by his wife. ‘Run the red light!’ My first thought when I read that was that should be his epitaph because that was how Alex Chilton lived his life.

HOLLY GEORGE-WARREN: Yeah, I guess that’s true. I know he wanted on his epitaph to be ‘A Self-Made Man’

PHAWKER: Well, he certainly was. He was DIY way before it was cool to be DIY. That was both his blessing and his curse, always just a little too ahead of his time.