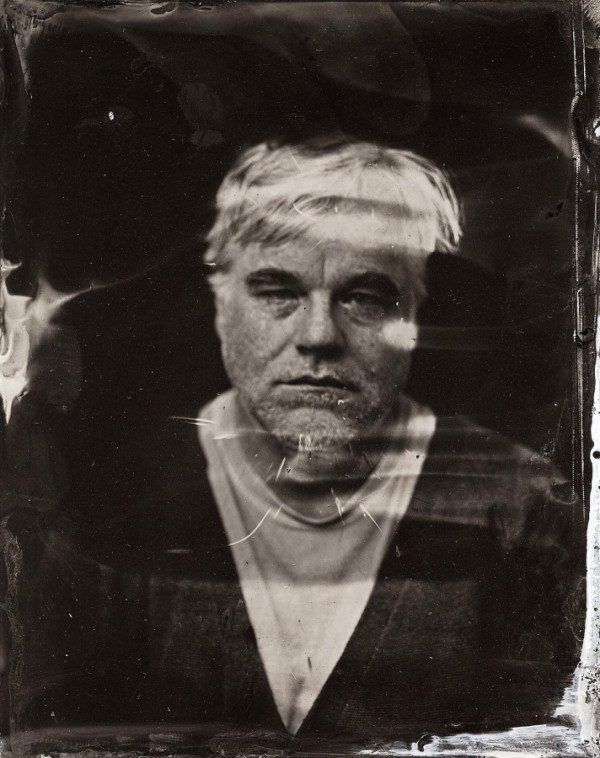

Photo by VICTORIA WILL

THE ATLANTIC: Naloxone, a non-narcotic, easily-dispensed medication, is being hailed as a miracle drug for reversing overdoses. Like Lazarus, an overdosed user on the verge of death will spring back to life when Naloxone mist hits his nostrils. Police are becoming more willing to carry and dispense the drug. More townships are passing Good Samaritan laws that make it safe for other drug users to contact emergency responders in the event of an overdose, without having to worry about getting arrested for having made the call. Advocates want Naloxone, which is safe and non-toxic, to be available over the counter. Had Hoffman followed simple instructions from a Naloxone training session (Don’t use alone. Train  those who use with you to administer the drug.), he might still be with us. Not every overdose can be prevented, but we should strive to prevent as many as possible. Naloxone isn’t drug treatment, and many who have their overdoses reversed will continue to use drugs, but we can’t get hung up on this. Dead people can’t get clean. Every reversed overdose is another chance at life.

those who use with you to administer the drug.), he might still be with us. Not every overdose can be prevented, but we should strive to prevent as many as possible. Naloxone isn’t drug treatment, and many who have their overdoses reversed will continue to use drugs, but we can’t get hung up on this. Dead people can’t get clean. Every reversed overdose is another chance at life.

U.S. drug policies are shifting. Slowly, and not enough, but there is progress. Mandatory minimums are being phased out. Treatment is increasingly available to those caught up in the criminal justice system. As the Affordable Care Act begins to take effect, treatment will become more broadly funded, especially for the poor. There is concern among public health professionals, myself included, that the policy shift will fall short of what we need to change conditions for injecting drug users. Legal pot isn’t enough. For there to be an American version of Insite, Vancouver’s celebrated, medically-supervised, legal injecting space, the U.S. would need to decriminalize entirely.

If Philip Seymour Hoffman had taken his last bags to a legal injecting space, would he still be alive? Had he overdosed there, medical staff on call might have reversed it with Naloxone. Had he acquired an abscess or other skin infection, he could have sought nonjudgmental medical intervention. Perhaps injection site staff could have directed him back to treatment. Safe injecting sites are an amazing, life saving, humanity restoring intervention we can’t have because our laws preclude them. Too frequently, heroin addicts instead utilize abandoned buildings and vacant lots to shoot up in order to evade arrest. The risk for assault, particularly sexual assault for women, in off-the-grid, hidden get-high places  is incredible. Overdosed bodies are routinely pulled from such spaces in North Philadelphia. MORE

is incredible. Overdosed bodies are routinely pulled from such spaces in North Philadelphia. MORE

PACIFIC STANDARD: There is very little talk about addiction beyond the membership of SAG, and how a national epidemic is being ignored in favor of a War on Drugs—and by regulations that prevent heroin addicts from getting what very few dispute is the world’s best and most efficient treatment. There is only one short-term chemical therapy that actually obviates the wrenching withdrawal symptoms of any opiate. This therapy involves the administration of a therapeutic dose of ibogaine, an alkaloid derivative of a family of plants in Central West Africa that Bwiti worshipers have long used as a visionary sacrament. A dissociative and powerful psychedelic compound, ibogaine induces a dream-state described variously as beatific, clarifying, and terrifying; the after-effects, usually a hazy state of dull relaxation, can last a number of days. In the majority of reported cases in Europe and Africa, cravings disappear once the psychoactive iboga wears off. (You can watch a hamhanded Vice video of white guys imitating the Bwiti ritual here, if you really must.)

In the states, there’s a degree of mystery surrounding the process of ibogaine. This state of affairs is hardly an accident. Most scientists at R1 schools (especially those with a research budget to lose) are uncomfortable speaking publicly about the treatment because to do so is to league oneself with the black sheep of the American scientific community —psychedelic researchers, a culture still stained by the legacy of Timothy Leary’s decades-long LSD boosterism. Even tenured researchers express a certain skittishness when the subject arises. Organizations such as the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) seek to mend this division within the medical community, so far without much luck.

—psychedelic researchers, a culture still stained by the legacy of Timothy Leary’s decades-long LSD boosterism. Even tenured researchers express a certain skittishness when the subject arises. Organizations such as the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) seek to mend this division within the medical community, so far without much luck.

Rick Doblin, who earned a Ph.D. in public policy from Harvard’s Kennedy School and co-founded MAPS, has been a vocal proponent of psychedelic therapy since the mid-1980s and has helped produce recent MAPS studies on ibogaine’s promising curative applications in New Zealand and Mexico. Doblin also self-administered ibogaine in 1985 (video here) and tells me that “[ibogaine] remains one of the most important psychedelic experiences of my life, and one of the most important experiences of any kind. It has unique potential for helping people go through opiate withdrawal.” MORE

PHAWKER: We prefer to remember Mr. Hoffman not as they found him, a lapsed junkie who accidentally killed himself while self-medicating, but as he is in the final minutes of this 20-minute HD reel of outtakes from Paul Thomas Anderson’s masterpiece The Master — hands down Hoffman’s (and, for that matter, Joaquin Phoenix’s) greatest performance — smoking cigarettes with Joaquin and trying unsuccessfully, take after take, not to break up laughing as he utters the words from the script “I like Kools — the minty flavor.” Watching two masters of the artform at the complete and utter mercy of such a harmless and seemingly insignificant word — “minty” — you see their humanity shine through. Because watching someone laugh — not on a director’s cue or the behest of a script but genuinely, and like the rest of us, helplessly — is the closest you will ever get to glimpsing their soul. Goodnight Mr. Hoffman, wherever you are.