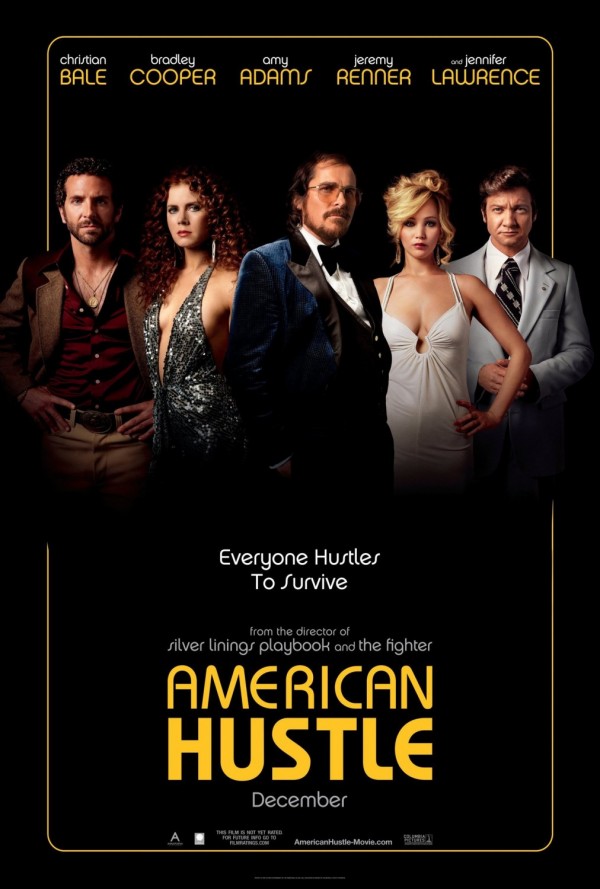

NEW YORKER: David O. Russell’s “American Hustle,” an intentionally overripe comedy about corruption, duplicity, loyalty, and love, is a series of astonishments. Russell, rewriting a script developed by Eric Singer, takes off from the Abscam affair—the bizarre criminal investigation of the nineteen-seventies in which the F.B.I. called on a swindler named Mel Weinberg to help ensnare public officials. (Six congressmen and a senator were among those ultimately convicted.) The bureau’s elaborate sting involved two “Arab sheikhs” (both F.B.I. employees) eager to invest in Atlantic City’s nascent casino industry and willing to bribe officials in order to procure operating licenses. (“Abscam” was short for “Abdul scam.”) Russell has both simplified and juiced a tale that is already close to preposterous; he has created a fantasia told from the point of view of two con artists, a man and a woman (based loosely on Weinberg’s mistress). Not just the crooks but virtually everyone in the movie seems slightly crazed by ambition. The one person who’s ordinary in temperament, an F.B.I. supervisor played by Louis C.K., could be a member of a different species. We seem to have stepped into the magical sphere—Shakespeare rules over it and Ernst Lubitsch and Preston Sturges are denizens—where profound human foolishness becomes a form of grace.

Christian Bale, bearded and forty pounds heavier, with a complex and unreliable hairpiece (parts of it come loose at unsuitable moments), is Irving Rosenfeld, who owns a chain of dry cleaners in New York and sells forged and stolen art on the side. Like all successful con men, Irving has a serene understanding of deception: most people, he’s sure, will believe what they want to believe. He’s deeply dishonest but not, in most ways, a terrible man. Irving wants things to work out for people; his half-goodness is part of the expanding joke of the movie. During a winter indoor-pool party at a friend’s house on Long Island, he meets an ambitious young woman, Sydney Prosser (Amy Adams), a former stripper, who is alarmingly intelligent and determined to make something of herself. She and Irving bond over a mutual love of Duke Ellington and begin an affair. Sydney also joins Irving’s scams, posing as a British aristocrat with banking connections; she wears dresses cleaved to the waist and boldly stares everyone down while quaking in her high heels. When the pair are caught by a high-strung F.B.I. agent, Richie DiMaso (Bradley Cooper), they wind up working for the bureau, carrying out Richie’s big-time sting. Racing around New York, Irving occasionally goes home to his luscious nutbrain wife, Rosalyn (Jennifer Lawrence), who has a habit of blundering into his arrangements at exactly the wrong time. The movie evokes such classics as “Married to the Mob,” “Goodfellas,” and “Prizzi’s Honor,” but it has a fizziness all its own and a pell-mell but lucid storytelling strategy that is one of the most impressive achievements in recent filmmaking. MORE

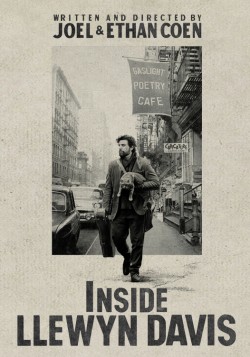

NEW YORK MAGAZINE: Joel and Ethan Coen’s Inside Llewyn Davis is an exquisitely crafted tale of woe with heartfelt early-sixties folk music—and an overarching snottiness. It’s a hell of a mix of tones, but that’s the  challenge the Coens’ movies pose: How do we reconcile their cheerfully disparate impulses? (Do we need to? We need to try.) Consider the setting: a pre–Bob Dylan Greenwich Village, scarred by McCarthyism but more and more alive to the stirrings of protest. The world is lovingly evoked, transcendently soundtracked (under the direction of T Bone Burnett). But it’s also the stage for a definitively downbeat story of an asshole folksinger who pays the piper for his bad personality. The film might be the ultimate proof that the Coens can find hopelessness in the darnedest places. […]

challenge the Coens’ movies pose: How do we reconcile their cheerfully disparate impulses? (Do we need to? We need to try.) Consider the setting: a pre–Bob Dylan Greenwich Village, scarred by McCarthyism but more and more alive to the stirrings of protest. The world is lovingly evoked, transcendently soundtracked (under the direction of T Bone Burnett). But it’s also the stage for a definitively downbeat story of an asshole folksinger who pays the piper for his bad personality. The film might be the ultimate proof that the Coens can find hopelessness in the darnedest places. […]

Inside Llewyn Davis is partly inspired by the late Dave Van Ronk, who conventional wisdom says was terminally overshadowed by his quasi protégé, Bob Dylan. Isaac bears little resemblance to Van Ronk, but the Coens evidently dug the idea of punishment arriving in the form of Dylan—the symbol for so many of us of rebirth. They’re mean that way. But there’s something deeper at work than mere nihilism. In his autobiography, The Mayor of MacDougal Street, Van Ronk notes the role of Jews as “folk revivalists” in search of authenticity who “adopted the music as part of a process of assimilation to the Anglo-American tradition.” I think the Coens are in search of the same authenticity, but for different ends. They want to show that blinkered stumblebums in a malignant universe can find transcendence via nativist works of art—but that art stands apart from wretched life. There’s no spillover. The tones of Inside Llewyn Davis can’t be reconciled because they’re meant to be irreconcilable. Once the music stops, you’re in the shit. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: Some viewers may be bored, however, as this legend meanders down a few comic blind alleys. A movie like “Anchorman 2,” in essence a very long character-based sketch, is always a hit-and-miss affair. The sheer density of the jokes guarantees a few laughs for every taste, though, and the loose, improvisational energy of the performers keeps things lively. The original cast members show the passage of time in their faces and bodies, with the uncanny exception of Mr. Rudd, the Dorian Gray of the New American Comedy. The sillier “Anchorman 2” gets, the better it works. In other words, it pretty much belongs to Mr. Carell, as the transcendently dim weatherman Brick Tamland, and to Kristen Wiig, as Chani, a co-worker who turns out to be Brick’s soul mate. Their romance lifts the movie into a realm of pure nonsense, and their graceful, inventive idiocy makes the rest of it look labored and overdone. Which is not to say that Brick and Chani should have their own movie. Too much of any one thing would spoil the fun of the whole, which depends on quick transitions from one setup to the next and an overall sense of anarchic busyness. “Anchorman 2” supplies that, as expected, even as it also feels like old news. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: Some viewers may be bored, however, as this legend meanders down a few comic blind alleys. A movie like “Anchorman 2,” in essence a very long character-based sketch, is always a hit-and-miss affair. The sheer density of the jokes guarantees a few laughs for every taste, though, and the loose, improvisational energy of the performers keeps things lively. The original cast members show the passage of time in their faces and bodies, with the uncanny exception of Mr. Rudd, the Dorian Gray of the New American Comedy. The sillier “Anchorman 2” gets, the better it works. In other words, it pretty much belongs to Mr. Carell, as the transcendently dim weatherman Brick Tamland, and to Kristen Wiig, as Chani, a co-worker who turns out to be Brick’s soul mate. Their romance lifts the movie into a realm of pure nonsense, and their graceful, inventive idiocy makes the rest of it look labored and overdone. Which is not to say that Brick and Chani should have their own movie. Too much of any one thing would spoil the fun of the whole, which depends on quick transitions from one setup to the next and an overall sense of anarchic busyness. “Anchorman 2” supplies that, as expected, even as it also feels like old news. MORE

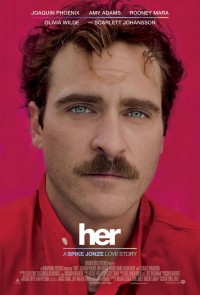

NEW YORK MAGAZINE: Is Jonze reworking his own personal history? In his ex-wife Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation (where Coppola’s alter-ego is played by Johansson—a bizarre  coincidence?), the husband (a music video director) is oblivious to his wife’s alienation. Her is an admission of that obliviousness and a lament for it. (Proof that Jonze has also evolved: Theodore’s fear that he’s sinking into himself, that everything he experiences will be a lesser version of what he has already experienced. No one who expresses an idea like that has stopped growing.) In Her, Jonze transforms his music-video aesthetic into something magically personal. The montages—silent, flickering inserts of Theodore and his ex-wife recollected in tranquility—are sublime. The soundtrack (songs by Karen O, Arcade Fire, The Breeders, and others) is unusually sensitive to the movement of the psyche. At one point, Samantha composes a piece of music to create a new way of capturing—in lieu of a photo—a wonderful afternoon. She’s doing what Jonze has been trying to do all his life—and what he does, in Her. MORE

coincidence?), the husband (a music video director) is oblivious to his wife’s alienation. Her is an admission of that obliviousness and a lament for it. (Proof that Jonze has also evolved: Theodore’s fear that he’s sinking into himself, that everything he experiences will be a lesser version of what he has already experienced. No one who expresses an idea like that has stopped growing.) In Her, Jonze transforms his music-video aesthetic into something magically personal. The montages—silent, flickering inserts of Theodore and his ex-wife recollected in tranquility—are sublime. The soundtrack (songs by Karen O, Arcade Fire, The Breeders, and others) is unusually sensitive to the movement of the psyche. At one point, Samantha composes a piece of music to create a new way of capturing—in lieu of a photo—a wonderful afternoon. She’s doing what Jonze has been trying to do all his life—and what he does, in Her. MORE

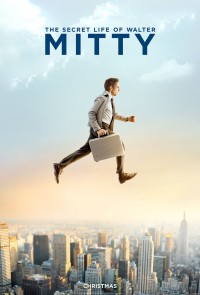

VARIETY: Sometimes daydreams do come true. At least, that’s what the Goldwyn family must be feeling now that their long-delayed “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” update finally exists, smarter and less screwball than previous attempts at the material have been. After nearly two decades of rewrites and recasting — during which Jim Carrey, Owen Wilson, Mike Myers and Sacha Baron Cohen were each attached — the role falls to Ben Stiller, who also directs. Rather than channeling James Thurber’s satirical tone, Stiller plays it mostly earnest, spinning what feels like a feature-length “Just Do It” ad for restless middle-aged auds, on whom its reasonably commercial prospects depend. MORE

VARIETY: Sometimes daydreams do come true. At least, that’s what the Goldwyn family must be feeling now that their long-delayed “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” update finally exists, smarter and less screwball than previous attempts at the material have been. After nearly two decades of rewrites and recasting — during which Jim Carrey, Owen Wilson, Mike Myers and Sacha Baron Cohen were each attached — the role falls to Ben Stiller, who also directs. Rather than channeling James Thurber’s satirical tone, Stiller plays it mostly earnest, spinning what feels like a feature-length “Just Do It” ad for restless middle-aged auds, on whom its reasonably commercial prospects depend. MORE

NPR: The Hobbit‘s path to the screen may have started out as tortuous as a trek through the deadly Helcaraxe, filled with detours (Guillermo del Toro was  initially going to direct), marked by conflict (New Zealand labor disputes) and strewn with seemingly insurmountable obstacles (so many that the filmmakers threatened to move the shoot to Australia). But with Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy having taken in almost $3 billion at the box office, there was never any real doubt that J.R.R. Tolkien’s remaining Middle-earth fantasy would ultimately become a film — or, as it happens, three of them. In that sense, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey isn’t “unexpected” at all, though between its lighter tone and a decade’s worth of improvements in digital film techniques, there should be enough of a novelty factor to delight most fans. After a sequence that recounts the eviction of the dwarves from their Lonely Mountain kingdom by the treasure-coveting dragon Smaug, Jackson takes us to the Shire, 60 years before the Rings cycle. Frodo’s adopted Uncle Bilbo, played by LOTR‘s Ian Holm in a framing sequence and by a smartly cast Martin Freeman thereafter, is a comparative youngster, while Gandalf (Ian McKellen) looks as old as the New Zealand hills. “I’m looking for someone,” says the wizard, “to share in an adventure.” MORE

initially going to direct), marked by conflict (New Zealand labor disputes) and strewn with seemingly insurmountable obstacles (so many that the filmmakers threatened to move the shoot to Australia). But with Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy having taken in almost $3 billion at the box office, there was never any real doubt that J.R.R. Tolkien’s remaining Middle-earth fantasy would ultimately become a film — or, as it happens, three of them. In that sense, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey isn’t “unexpected” at all, though between its lighter tone and a decade’s worth of improvements in digital film techniques, there should be enough of a novelty factor to delight most fans. After a sequence that recounts the eviction of the dwarves from their Lonely Mountain kingdom by the treasure-coveting dragon Smaug, Jackson takes us to the Shire, 60 years before the Rings cycle. Frodo’s adopted Uncle Bilbo, played by LOTR‘s Ian Holm in a framing sequence and by a smartly cast Martin Freeman thereafter, is a comparative youngster, while Gandalf (Ian McKellen) looks as old as the New Zealand hills. “I’m looking for someone,” says the wizard, “to share in an adventure.” MORE