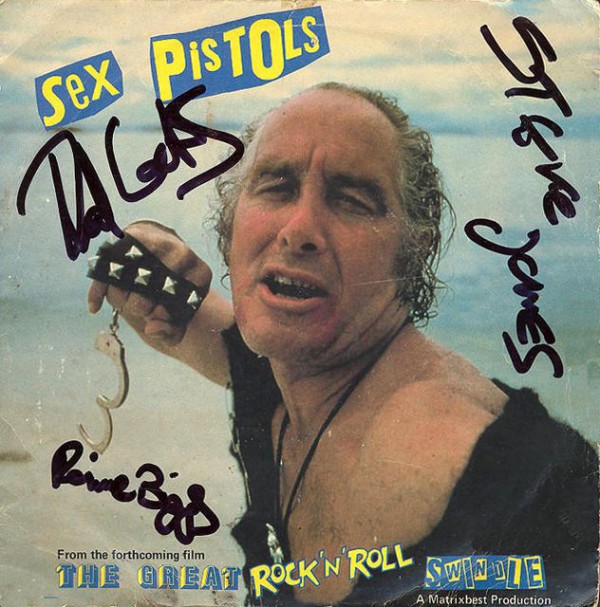

NEW YORK TIMES: Ronnie Biggs, a carpenter and petty crook who became an international celebrity for his role in one of Britain’s most famous crimes, the Great Train Robbery of 1963, and for the decades he spent afterward eluding a worldwide manhunt by Scotland Yard, died on Wednesday in London. He was 84. “Sadly we lost Ron during the night,” they wrote in a Twitter feed. “As always, his timing was perfect to the end.” A long-scheduled two-part dramatization of the Great Train Robbery, a half century after it took place, is to be broadcast by the BBC on Wednesday and Thursday. Imprisoned in England since he returned there voluntarily in 2001, Mr. Biggs was granted compassionate release for health reasons in August 2009 by Jack Straw, the British justice secretary at the time. The decision was a highly public reversal by Mr. Straw, who had earlier denied Mr. Biggs’s application, saying he had shown no remorse for the crime, in which 15 men robbed a Glasgow-to-London mail train of more than $7 million in bank notes. The train’s driver was seriously injured. […] Mr. Biggs’s enduring reputation stemmed not so much from the heist itself as from what happened afterward. Tried and convicted, he escaped from prison and became the subject of an international manhunt; spent the next 36 years as a fugitive, much of that time living openly in Rio de Janeiro in defiance of the British authorities; and enjoyed almost preternatural luck in thwarting repeated attempts to bring him to justice, including being kidnapped and spirited out of Brazil by yacht. The fact that the robbery happened to take place on Mr. Biggs’s birthday also did not hurt. During his years at large, Mr. Biggs, aided by the British tabloid press, cultivated his image as a working-class Cockney hero. He sold memorabilia to tourists, endorsed products on television and recorded a song (“No One Is Innocent”) with the Sex Pistols, the British punk band. As much as anything, Mr. Biggs’s story is about the construction of celebrity, and the ways in which celebrity can be sustained as a kind of cottage industry long after the world might reasonably be expected to have lost interest. MORE

Curated News, Culture And Commentary. Plus, the Usual Sex, Drugs and Rock n' Roll