Photo by BRIGITTE LACOMBE

NEW YORK MAGAZINE: Spike Jonze first emerged as a movie director as part of the “class of ’99,” making his debut in what turned out to be an epochal year that also saw breakthroughs for the Wachowskis, Kimberly Peirce, David O. Russell, Brad Bird, and Tom Tykwer, not to mention Jonze’s then-bride Sofia Coppola (the two married in 1999 and divorced in 2003). His contribution to the new-generation vibe of that moment was particularly auspicious: After winning good reviews for his first major acting role, as a hayseed soldier in Russell’s acclaimed Three Kings, he arrived months later as a director with Being John Malkovich, a surreal dark comedy about a sad-sack starving artist (John Cusack) who discovers a portal that allows him—or anyone else—to jump into the consciousness of the title character.

Jonze had won respect as a music-video director for Weezer, Daft Punk, and the Beastie Boys at a time when that was still primarily a dismissive term; his videos often felt like performance-art installations in which viewers were confronted with a technical innovation (the Pharcyde’s “Drop” is a long take that you gradually realize is being played backward), a haunting image (a man running down the street on fire in California’s “Wax”), or a put-on without a trace of snideness (the amateur public dance performance in Fatboy Slim’s “Praise You,” with Jonze co-starring as choreographer “Richard Koufey”).* But the soulfulness and assurance with which he handled screenwriter Charlie Kaufman’s genre-busting script still came as a huge surprise. Jonze won the New York Film Critics Award for Best First Film and, at 30, an Oscar nomination for Best Director, the first time the Academy had ever recognized someone so strongly identified with the disdained realm of MTV. He says it was only around then that he started watching movies seriously: “I wasn’t a film kid,” he says, citing Fargo and Hal Ashby especially for showing him that movies could have many tones at once. “I think I probably suffered  from what a lot of young people suffered from—‘Oh, that’s going to be old, that’s going to be old-fashioned.’ I’ve definitely thought, Oh, that’s a classic movie and then seen it and thought, Oh, no, no, that’s a great movie!” Malkovich was a high-end indie (it was made for $13 million), but now, the major studios were eager to get their hands on him. When he and Kaufman reteamed in 2002 for Adaptation, the result was every bit as acclaimed as Malkovich had been, and this time, Sony was writing the checks.

from what a lot of young people suffered from—‘Oh, that’s going to be old, that’s going to be old-fashioned.’ I’ve definitely thought, Oh, that’s a classic movie and then seen it and thought, Oh, no, no, that’s a great movie!” Malkovich was a high-end indie (it was made for $13 million), but now, the major studios were eager to get their hands on him. When he and Kaufman reteamed in 2002 for Adaptation, the result was every bit as acclaimed as Malkovich had been, and this time, Sony was writing the checks.

The critical success of his first two pictures won him the chance to work on a larger scale, but on his next movie, an adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are for Warner Bros., released in 2009, that Jonze co-wrote with the novelist Dave Eggers, “nothing was easy.” With a $100 million budget came the constraints of working for a studio that wanted something “indie” enough to please critics while still functioning as a family-friendly brand name. Given its prep time, its technical complexities (dubbing, puppetwork, CGI), and a protracted postproduction during which he and the studio fought over the film’s tone, “it was really like making six movies,” he recalls. Ultimately, Warner Bros. supported Jonze—Wild Things was an uncompromised, independent-feeling film with no blockbuster gloss, and it won the ardent admiration of many critics. But its exactly-break-even $100 million worldwide gross was disappointing, and it arrived at a post-crash moment when many studios were retreating from their flirtations with indie sensibilities.

Jonze, who had never before had his vision challenged by a studio’s economic imperatives, felt so wrung out that he took a year off before starting to write again. “I just wanted short, fun, interesting challenges,” he says. “If a movie is like a painting, I wanted to do sketches. When I used to make music videos all the time, that’s what they were like. ‘Here’s an artist I love, here’s a song I love, here’s an idea, let’s go make it.’ But this time I wanted to do things that originated from an idea I had as opposed to a song.” He and Kanye West collaborated on a short movie called We Were Once a Fairytale, and he co-directed a stop-motion-animation short called Mourir Auprès de Toi (To Die by Your Side), using characters made of felt. Then he accepted a commission from Absolut Vodka to direct another short, an idea that grew into I’m Here, a romantic seriocomedy about young love and sacrifice in contemporary Los Angeles—except with robots. The 31-minute film, which stars Andrew Garfield, feels in many ways like a warm-up for his new movie. MORE

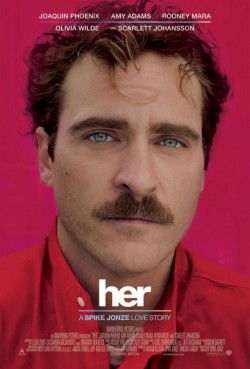

DAVID EDELSTEIN: A lonely man (Joaquin Phoenix) who writes personal letters for other people (they can’t say what they want to say themselves) forms a wondrous bond with his Operating System (voiced by Scarlett Johansson)—which (who?) becomes more and more sentient. Spike Jonze’s futuristic comedy is an exquisite meditation on love, friendship, human connection, and the singularity that might enlarge (or possibly contract) our definition of what that connection means. In the first hour, there’s a vein of satire—of the supreme silliness and pathos of a world in which people turn increasingly to disembodied voices for solace, friendship, sex. (Can you really “date” an OS?) But the satire yields to a sort of transcendental romanticism that leaves you both heartbroken and full of wonder. This is like no other movie—although it’s clearly a descendant of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. (Is Charlie Kaufman the new high priest—the William Gibson—of futuristic psychodrama?) Her is not just the best film in years, it has the best performance of 2013 by a cosmic margin. Perhaps no actor but Phoenix could express emotions that are so painfully unformed. He’s not just unafraid of regressing, of getting lost—he lives for it. MORE