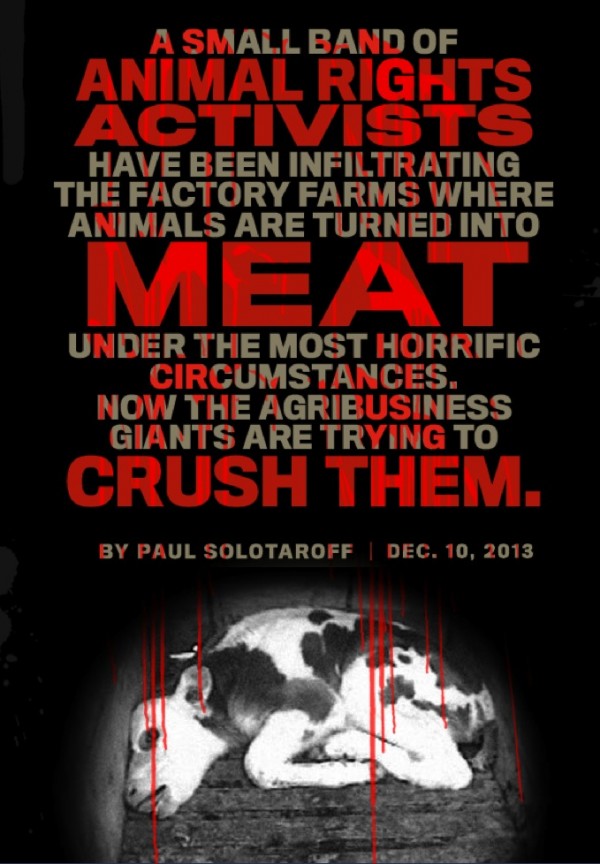

ROLLING STONE: Sarah – let’s call her that for this story, though it’s neither the name her parents gave her nor the one she currently uses undercover – is a tall, fair woman in her midtwenties who’s pretty in a stock, anonymous way, as if she’d purposely scrubbed her face and frame of distinguishing characteristics. Like anyone who’s spent much time working farms, she’s functionally built through the thighs and trunk, herding pregnant hogs who weigh triple what she does into chutes to birth their litters and hefting buckets of dead piglets down quarter-mile alleys to where they’re later processed. It’s backbreaking labor, nine-hour days in stifling barns in Wyoming, and no training could prepare her for the sensory assault of 10,000 pigs in close quarters: the stench of their shit, piled three feet high in the slanted trenches below; the blood on sows’ snouts cut by cages so tight they can’t turn around or lie sideways; the racking cries of broken-legged pigs, hauled into alleys by dead-eyed workers and left there to die of exposure. It’s the worst job she or anyone else has had, but Sarah isn’t grousing about the conditions. She’s too busy waging war on the hogs’ behalf.

We’re sitting across the couch from a second undercover, a former military serviceman we’ll call Juan, in the open-plan parlor of an A-frame cottage just north of the Vermont-New York border. The house belongs to their boss, Mary Beth Sweetland, who is the investigative director for the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) and who has brought them here, first, to tell their stories, then to investigate a nearby calf auction site. Sweetland trains and runs the dozen or so people engaged in the parlous business of infiltrating farms and documenting the abuse done to livestock herds by the country’s agri-giants, as well as slaughterhouses and livestock auctions. Given the scale of the business – each year, an estimated 9 billion broiler chickens, 113 million pigs, 33 million cows and 250 million turkeys are raised for our consumption in dark, filthy, pestilent barns – it’s unfair to call this a guerrilla operation, for fear of offending outgunned guerrillas. But what Juan and Sarah do with their hidden cams and body mics is deliver knockdown blows to the Big Meat cabal, showing videos of the animals’ living conditions to packed rooms of reporters and film crews. In many cases, these findings trigger arrests and/or shutdowns of processing plants, though the real heat put to the offending firms is the demand for change from their scandalized clients – fast-food giants and big-box retailers. “We’ve had a major impact in the five or six years we’ve been doing these operations,” says Sarah.

In its scrutiny of Big Meat – a cartel of corporations that have swallowed family farms, moved the animals indoors to prison-style plants in the middle of rural nowhere, far from the gaze of nervous consumers, and bred their livestock to and past exhaustion – the Humane Society (and outfits like PETA and Mercy for Animals) is performing a service that the federal government can’t, or won’t, render: keeping an eye on the way American meat is grown. That’s rightfully the job of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, but the agency is so short-staffed that it typically only sends inspectors out to slaughterhouses, where they check a small sample of pigs, cows and sheep before they’re put to death. That hour before her end is usually the only time a pig sees a government rep; from the moment she’s born, she’s on her own, spending four or five years in a tiny crate and kept perpetually pregnant and made sick from breathing in her own waste while fed food packed with growth-promoting drugs, and sometimes even garbage. (The word “garbage” isn’t proverbial: Mixed in with the grain can be an assortment of trash, including ground glass from light bulbs, used syringes and the crushed testicles of their young. Very little on a factory farm is ever discarded.)

Save the occasional staffer who becomes disgruntled and uploads pictures of factory crimes on Facebook, undercover activists like Juan and Sarah are our only lens into what goes on in those plants – and soon, if Big Meat has its way, we’ll not have even them to set us straight. A wave of new laws, almost entirely drafted by lawmakers and lobbyists and referred to as “Ag-Gag” bills, are making it illegal to take a farm job undercover; apply for a farm job without disclosing a background as a journalist or animal-rights activist; and hold evidence of animal abuse past 24 to 48 hours before turning it over to authorities. Since it takes weeks or sometimes months to develop a case – and since groups like HSUS have pledged not to break the law – these bills are stopping watchdogs in their tracks and giving factory farmers free rein behind their walls. Three states – Iowa, Utah and Missouri – have passed such measures in the past two years, and more are likely to follow. “That’s why we’ve come forward: People need to fight while there’s still time,” says Sarah. “We’re not trying to end meat or start a panic. But there’s a decent way to raise animals for food, and this is the farthest thing from it.” MORE