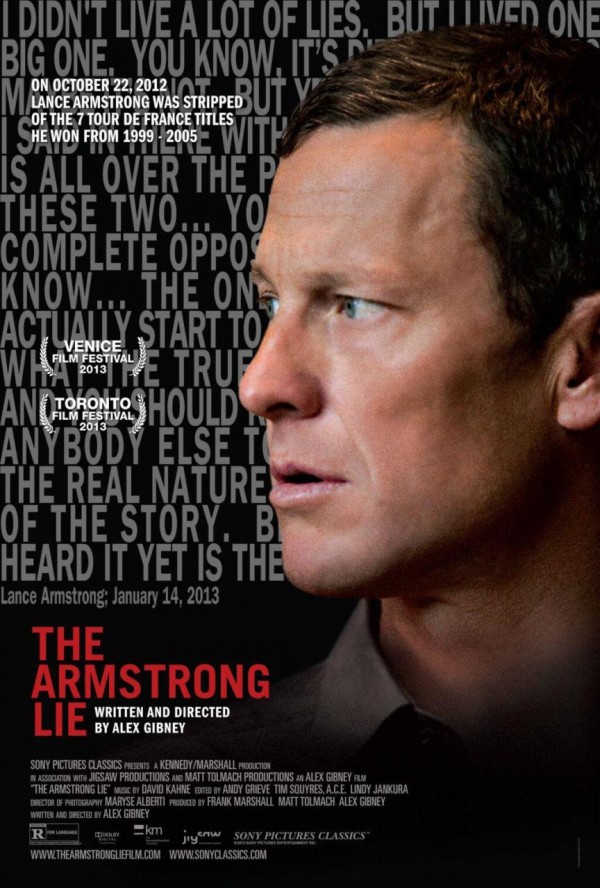

THE ARMSTRONG LIE (2013, directed by Alex Gibney, 122 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Alex Gibney’s latest documentary The Armstrong Lie seems bound to come and go quickly if only because its subject has already been road-tested as a giant fib no one wants to hear. Beating the French seven times at their own game and coming back from cancer even stronger, now that’s a story to promote and cheer. The real story, that Armstrong’s Tour de France wins were the product of shameless blood doping is a drag we would all like to forget. But Gibney hasn’t forgotten, perhaps because he was personally lied to by Armstrong himself, but the filmmaker also makes the case that the Armstrong saga has something to tell us abut the seductiveness of a great story and how normal people can find themselves doing battle against unfortunate truths.

The Armstrong Lie is so watchable in part because, true or false, the story is such a good one. Rawboned and ruggedly handsome, Armstrong came out of Texas, already a tireless trainer when he competed in triathlons as a teenager and Second Place was simply not an option. He did well as bicycle racer in the early ’90s before being struck down by testicular cancer in 1996. Although the cancer had spread to his lungs and brain, Armstrong came back not only stronger, but went on to win the Tour de France a record seven times. “Take that you cheese-eating surrender-monkeys!”

It’s thrilling stuff even if you know it ain’t true. There is a Libertarian streak that says “Who cares? The whole sport is dirty and Armstrong came out on top.” Gibney argues that the massive sums of money that came along with the Armstrong lie gave Lance an unfair advantage in trailblazing new techniques for chemically-catapaulting one’s body into near-superhuman heights of athletic achievement. Armstrong was also in partnership with some of the racing officials in other ventures which present a classic conflict-of-interest. Once the cats are out of the bag, the viciousness in which Armstrong attacks those who tell the truth will help wither most of the waning affections of those who followed his shooting star.

A story like this would just be something for SportsCenter to report on if Armstrong wasn’t the very public face of the “Live Strong” campaign for cancer research. When you present your story as an inspiration for the seriously ill the lie suddenly takes on a deeper cruelty that is hard to shake, even if millions are being raised for a good cause. It underlines the vulnerability present in many institutions when they build false fables about their goodness and fairness. Much of the injury institutions sustain in such moral scandals comes from how strenuously they defend their lies once they are uncovered.

Having admittied to his deceptions earlier in the film, Lance appears to lie again in the film’s final interview. By the end Armstrong’s character has his weaknesses spread out like guts for the whole world to see. His tired eyes and defensive stance make him appear exhausted by a ride that took him from champion and humanitarian and ultimately to disgrace. Gibney doesn’t ask us for pity but it is easy to think that Armstrong’s love of the big lie has given him the worst ride of all.