The truly heroic do not take up arms and kill for king and country. The truly heroic forswear violence and set their people free. Ghandi, Martin Luther King, Jesus Christ, Nelson Mandela. These are men with more guts than a thousand John Waynes. They came in the name of love — a love that made them more powerful than you can possibly imagine — and vanquished the tyranny of evil men. Tell your children.

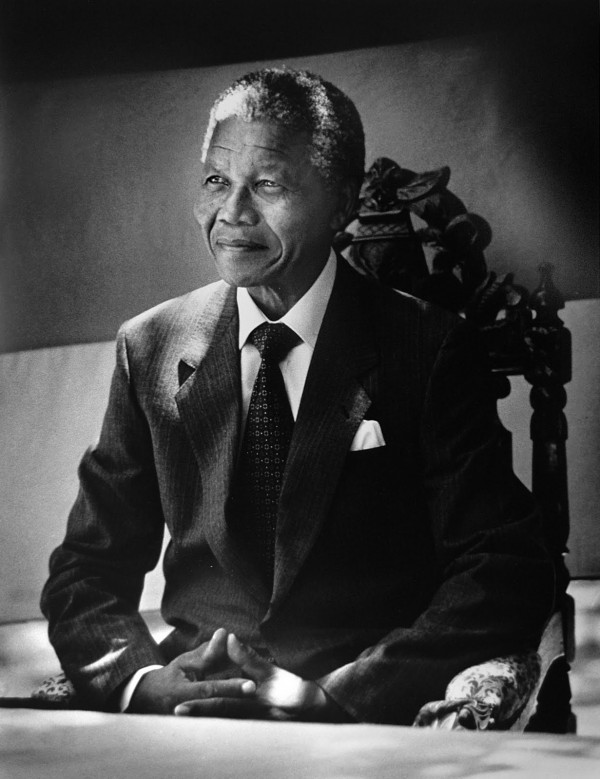

NEW YORK TIMES: Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s first black president and an enduring icon of the struggle against racial oppression, died on Thursday, the government announced, leaving the nation without its moral center at a time of growing dissatisfaction with the country’s leaders. “Our nation has lost its greatest son,” President Jacob Zuma said in a televised address on Thursday night, adding that Mr. Mandela had died at 8:50 p.m. local time. “His humility, his compassion and his humanity earned him our love.” Mr Zuma called Mr. Mandela’s death “the moment of our greatest sorrow,” and said that South Africa’s thoughts were now with the former president’s family. “They have sacrificed much and endured much so that our people could be free,” he said. Mr. Mandela spent 27 years in prison after being convicted of treason by the white minority government, only to forge a peaceful end to white rule by negotiating with his captors after his release in 1990. He led the African National Congress, long a banned liberation movement, to a resounding electoral victory in 1994, the first fully democratic election in the country’s history. Mr. Mandela, who was 95, served just one term as South Africa’s president and had not been seen in public since 2010, when the nation hosted the soccer World Cup. But his decades in prison and his insistence on forgiveness over  vengeance made him a potent symbol of the struggle to end this country’s brutally codified system of racial domination, and of the power of peaceful resolution in even the most intractable conflicts. MORE

vengeance made him a potent symbol of the struggle to end this country’s brutally codified system of racial domination, and of the power of peaceful resolution in even the most intractable conflicts. MORE

TIME: Relentlessly pounded by the angry surf and chilled by the icy winds of the south Atlantic, Robben Island is the unlikely cradle of South African democracy. That wasn’t exactly what the Dutch and British empires had in mind when they began, from the 17th century, using the two-square mile rocky outcrop four miles off Cape Town as a prison. Being sent to live out their day on Robben Island was the fate of those who dared resist the incursion of European settlers. And the white-minority regime that inherited the reins of colonial power maintained that tradition.

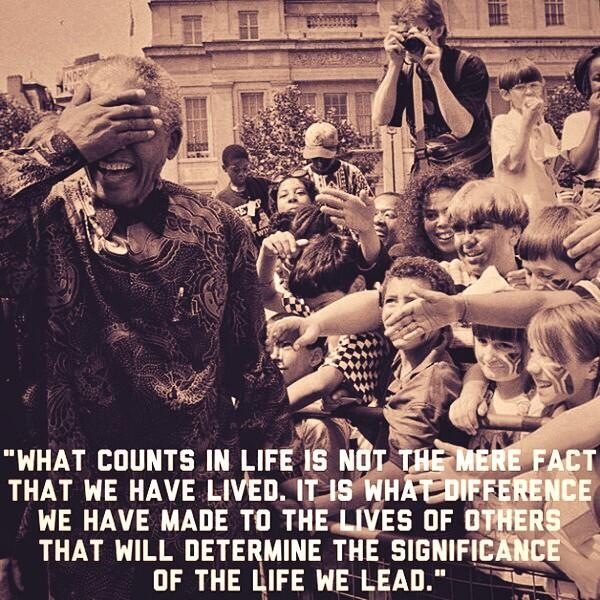

Nelson Mandela, leader of the armed wing of the African National Congress spent 18 of his 27 years in prison there, and emerged to lead all South Africans, black and white, in a process of democratic reconciliation that became a global icon of humanity’s ability to transcend racism. But three centuries before Mandela broke rocks in its dusty quarry, the Island (as it was known in South Africa) had held the indigenous leader Autshumao, known to the Dutch as “Harry the Beachcomber”, mutinous slaves brought to the Cape from the Dutch East Indies, and the Xhosa insurgent leader Makana who had risen against the British in 1819.

But it was Mandela and his cohort who put the Island on the international map. Having taken up arms against the apartheid regime when all channels of peaceful protest were closed by violent repression, their insurgency was crushed, and like Autshumao and Makana before them, they were sent to rot on the Island, their fate intended as an object lesson to all who would dare challenge the authority of the white man. Things didn’t work out that way. Despite the best efforts of the prison authorities to break their spirit, the prisoners organized themselves and steadily expanded their control of the institution’s culture. The Island became known as “the university of the struggle,” each new wave of young rebels brought to the prison falling under the tutelage of Mandela’s generation, leaving the prison to rejoin the fight with the equivalent of a revolutionary MBA. MORE

THE TELEGRAPH: From day one, Mandela maintained a kind of dignity that we began to model ourselves on. One day, they allowed us to walk to the quarry instead of taking us there in trucks. We walked in rows of four, in a column with warders in front, behind and to each side, demanding that we ran. Mandela whispered to us: ‘Chaps, slow down’. I remember just seething with the impossibility of what he was asking because the atmosphere was menacing and even if you wanted to slow down, it made you walk faster. Mandela crept through the rows until he was in the front and there, he started setting the pace. Everything was slowing down and the warders were screaming and that’s when you realised that they could do nothing – they were helpless. We hadn’t sworn at them, we hadn’t talked back to them, all that had happened was that we were just walking slowly and suddenly we’d conquered the fear that was getting our muscles to move involuntarily. It was the slowest walk to the quarry but my overwhelming recollection is of the dignity that went with that walk. It won a round for us without bending to the rules they set. We had made the rules. That gives you a tremendous sense of moral superiority. MORE

THE GUARDIAN: Extracts from Nelson Mandela’s statement from the dock at the opening of his trial on charges of sabotage at the supreme court of South Africa in Pretoria on 20 April 1964. Mandela, leader of the African National Congress and of the struggle against the racist apartheid regime, was given a life sentence, of which he served 27 years, most of which was in the prison on Robben Island. MORE