NEW YORKER: If you love the Coens, or follow folk music, or hold fast to this period of history and that patch of New York, then the film can hardly help striking a chord. Some of its joys are gleefully precise, like the quartet of white-sweatered harmonizing Irish crooners, or the novelty number “Please Mr. Kennedy,” which Llewyn, Jim, and Al Cody (Adam Driver) chant for Columbia Records. Yet something in the movie fails to grip, and it has to do with the hero. Bud Grossman, again, gets it right, telling him, “You’re no front man.” If that is bad news for a musician, it’s worse for a dramatic lead, and, as though to compensate for this lack of energy at the core, the Coens plump up their peripheral figures—people like Roland Turner (John Goodman), a jazzman who is given not just a pair of walking sticks, like the lawyer in “The Lady from Shanghai,” but a drug habit and a funny toupee to boot. Being Goodman, he provides a juicy distraction, though before long we return to the gloom of Llewyn. He’s such a grouch and an ingrate, and so allergic to human sympathy, that, like his friends, we can’t always be bothered to extend it. Also, he never looks as poor and as starving as he is meant to, or even very down-at-heel. In fact, the whole movie is so beautifully shot, by Bruno Delbonnel, that, if anything, the beauty hazes over the shabby desperation that, by custom, should plague the struggling artist. MORE

HOLLYWOOD REPORTER: There’s a scene from Inside Llewyn Davis where folk singer Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac) reluctantly participates in the recording of a novelty song called “Please Mr. Kennedy (Don’t Send Me Into Outer Space).” The already much-shared clip, which features actors Isaac, Driver (of Girls fame) and Justin Timberlake, realistically depicts the session creation of this silly little ditty. But where did the quirky composition originally come from? And who deserves to get paid for it? Burnett’s rep explains that the music maestro and the Coens adapted their song “Please Mr. Kennedy” from another novelty song of the same name that came out on the 1962 album Here They Are by The Goldcoast Singers. That tune depicts a comical draft-board scenario where some shaggy rock ‘n’ rollers beg President John F. Kennedy not to enlist them into the army. Since these lyrics were modified for the film (making it ineligible for a best original song Oscar), the new songwriting credit shows original writers Ed Rush and George Cromarty now accompanied by Burnett, the Coens and Timberlake.

That’s interesting, because in December 1961, the Tamla-Motown label released a 45 single entitled “Please Mr. Kennedy (I Don’t Want to Go)” by Mickey Woods, and you can easily hear the similarity between that war-phobic plea and the Coen creation. Credits for that particular tune actually list Berry Gordy, Loucye Wakefield and Ronald Wakefield as the song’s composers — no trace of Messrs. Rush or Cromarty here. Before Mr. Gordy starts calling his attorneys, we have to further note that it’s fairly obvious the Motown folks lifted their novelty song directly from the No. 1 Billboard hit “(Please) Mr. Custer” sung by Larry Verne, which was released a year earlier in 1960 on Era Records and written by Al De Lory, Fred Darian and Joseph Van Winkle. Structurally, all four tunes have plenty in common. And much the same way that Justin Timberlake’s character doesn’t want to go into space, The Goldcoast Singers and Mickey Woods tell the president they’re reluctant to go to war — and the politically incorrect Verne shamelessly implores Gen. George Armstrong Custer not to take him along to Little Big Horn. He’s got a bad feeling. MORE

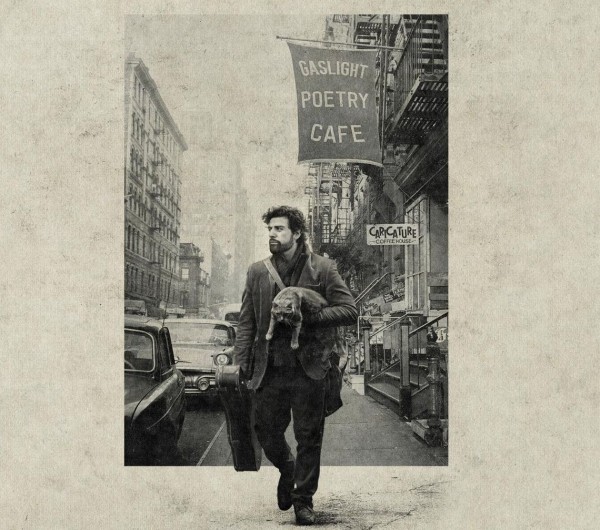

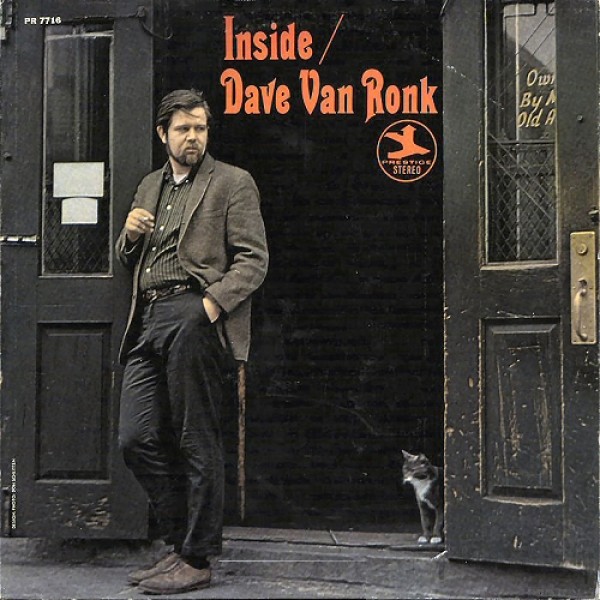

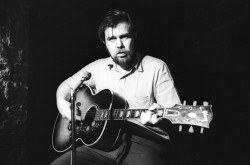

NEW YORK TIMES: Llewyn’s repertoire and some aspects of his background are borrowed from Dave Van Ronk, who loomed large on the New York folk scene in its pre-Bob Dylan hootenanny-and-Autoharp phase. Oscar Isaac, who plays both Llewyn and the guitar with offhand virtuosity, is slighter of build and scowlier of mien than Van Ronk, with a fine, clear tenor singing voice. But in any case, this is not a biopic, it’s a Coen brothers movie, which is to say a brilliant magpie’s nest of surrealism, period detail and pop-culture scholarship. To put it another way, it’s a folk tale. But if Llewyn is an archetype, he is also a familiar kind of Coen antihero, the latest face in the gallery of losers, deadbeats and hapless strivers the brothers have been assembling, over 16 features, for nearly 30 years. These dudes are usually at the mercy of other people, a hostile universe and their own stupidity. Above all, they are the playthings of a pair of cruel and capricious fraternal deities whose affection for their creatures is often indistinguishable from contempt. MORE

ROLLING STONE: Born in Brooklyn in 1936, Dave Van Ronk moved to the Village as a teenager and never left. Over five decades, he recorded scores of albums that blended blues, jazz, jug-band stomping, and sea chanteys. He was an early champion of Dylan and other up-and-coming songwriters like Joni Mitchell. When Joan Baez was beginning her own career in the Boston and Cambridge areas, she would hear reports of Van Ronk, who was a few years older than her. “He was already a myth,” Baez says. “He had terrible teeth, but he had the most astonishing pitch, sweet little notes amidst the growly ones. I knew thousands of people who sang the blues, but there weren’t many who did it well. He was the closest living offshoot of Leadbelly that I could get to see.” Although Van Ronk never sold anywhere near the amount of  records his protégés did, he accumulated many boldface-name fans. In Chronicles Volume One, Dylan wrote that he’d first heard Van Ronk’s records while growing up in the Midwest. “He was passionate and stinging,” wrote Dylan, “sang like a solder of fortune and sounded like he paid the price. . . I loved his style.” Tom Waits (whose voice recalls Van Ronk’s) has long been an admirer, and Stephen King dropped Van Ronk’s name in his novella Riding the Bullet. Vuocolo Van Ronk, who met Van Ronk in the Seventies but didn’t hook up with him until the early Eighties (Van Ronk was married before, to Terri Thal), recalls the time she and Van Ronk had just returned home to their Village apartment after a trip. There was a knock on the door, and expecting it to be Van Ronk, who’d run out for an errand, she opened it — and found Dylan standing there. “Dave around?” he asked. She invited him in and offered him coffee, and the two waited for Van Ronk to show up, after which the two men talked for hours. “I thought, ‘Bob Dylan is sitting in my living room,'” says Vuocolo Van Ronk. “He seemed a little nervous, but he wanted to be alone with Dave, and Dave was very happy to see him.” Inside Llewyn Davis slips in more than a few details from Van Ronk’s memoir. Like Van Ronk, Davis spends time in the merchant marines, schleps to Chicago to unsuccessfully audition for the famed Gate of Horn club, rejects the idea of joining a Peter, Paul and Mary-style folk group, and complains to the head of his record company that he’s so broke he can’t afford a winter coat. MORE

records his protégés did, he accumulated many boldface-name fans. In Chronicles Volume One, Dylan wrote that he’d first heard Van Ronk’s records while growing up in the Midwest. “He was passionate and stinging,” wrote Dylan, “sang like a solder of fortune and sounded like he paid the price. . . I loved his style.” Tom Waits (whose voice recalls Van Ronk’s) has long been an admirer, and Stephen King dropped Van Ronk’s name in his novella Riding the Bullet. Vuocolo Van Ronk, who met Van Ronk in the Seventies but didn’t hook up with him until the early Eighties (Van Ronk was married before, to Terri Thal), recalls the time she and Van Ronk had just returned home to their Village apartment after a trip. There was a knock on the door, and expecting it to be Van Ronk, who’d run out for an errand, she opened it — and found Dylan standing there. “Dave around?” he asked. She invited him in and offered him coffee, and the two waited for Van Ronk to show up, after which the two men talked for hours. “I thought, ‘Bob Dylan is sitting in my living room,'” says Vuocolo Van Ronk. “He seemed a little nervous, but he wanted to be alone with Dave, and Dave was very happy to see him.” Inside Llewyn Davis slips in more than a few details from Van Ronk’s memoir. Like Van Ronk, Davis spends time in the merchant marines, schleps to Chicago to unsuccessfully audition for the famed Gate of Horn club, rejects the idea of joining a Peter, Paul and Mary-style folk group, and complains to the head of his record company that he’s so broke he can’t afford a winter coat. MORE

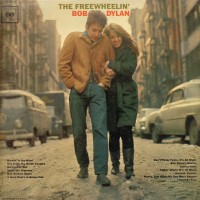

THE GUARDIAN: I do like the Coen brothers‘ wintry ones. Anyone who thinks composition is a purely visual matter should re-watch Fargo, which happily inverted the old film noir tradition which says kidnappings and extortion should come wrapped in expressionistic shadow. Instead, the film pitched daylight robbery against a blinding white tundra – film blanc – with particular attention paid to the way the Minnesota winter obliterates the horizon line. The characters just seemed to hanging there twixt land and sky, like Bellow’s dangling man, caught between two voids, unsure which  way is up. The Coens’ collaborators are said to feel much the same way. The snow that covers much of Inside Llewyn Davis is another matter again: it’s the kind of old, grey city snow that car exhaust stains brown, and gets into your boots on the long trudge home. We can be even more precise that that, I think: it’s the kind of snow you see covering the East Village street walked by Bob Dylan, arm-in-arm with Suzy Rotolo, on the cover on Freewheelin’, as dawn breaks at behind them. Inside Llewyn Davis is set in the days preceding that dawn.

way is up. The Coens’ collaborators are said to feel much the same way. The snow that covers much of Inside Llewyn Davis is another matter again: it’s the kind of old, grey city snow that car exhaust stains brown, and gets into your boots on the long trudge home. We can be even more precise that that, I think: it’s the kind of snow you see covering the East Village street walked by Bob Dylan, arm-in-arm with Suzy Rotolo, on the cover on Freewheelin’, as dawn breaks at behind them. Inside Llewyn Davis is set in the days preceding that dawn.

NEW YORK TIMES: There is nonetheless a strong, hidden current of social criticism in the [Coen] brothers’ work, which casts a consistently skeptical eye on the American mythology of success. Winners do not interest them. There’s no success like failure, and failure’s no success at all. That observation was made by Bob Dylan, like Joel and Ethan Coen, a Jewish kid from Minnesota and, like them, possessed of a knack for conscripting the American popular art of the past into the service of his own idiosyncratic genius. His art, like theirs, upends easy distinctions between sincerity and cynicism, between the authentic and the artificial, and at once invites and resists interpretation. So I won’t speculate further on what “Inside Llewyn Davis” might mean. But at least one of its lessons seems to me, after several viewings, as clear and bright as a G major chord. We are, as a species, ridiculous: vain, ugly, selfish and self-deluding. But somehow, some of our attempts to take stock of this condition — our songs and stories and moving pictures, old and new — manage to be beautiful, even sublime. MORE