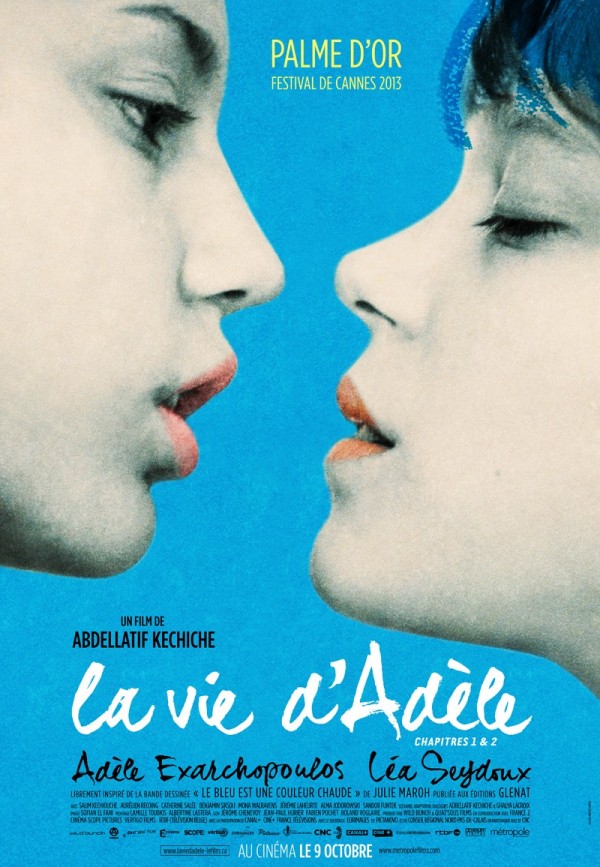

BLUE IS THE WARMEST COLOR (2013, Directed by Abdellatif Kechiche, 179 minutes, France)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC A bracingly intimate look at the debilitating flames of first love, Blue is the Warmest Color captures the gravitational force of young passion when it becomes all-consuming. At three hours long, the winner of last year’s Palm d’Or immerses us so deeply into the world of the introverted Adele that at film’s end she feels like a person we know rather then a character we merely observed.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC A bracingly intimate look at the debilitating flames of first love, Blue is the Warmest Color captures the gravitational force of young passion when it becomes all-consuming. At three hours long, the winner of last year’s Palm d’Or immerses us so deeply into the world of the introverted Adele that at film’s end she feels like a person we know rather then a character we merely observed.

The performances that Tunisian-French director Abdellatif Kechiche capture from his two female leads exude such honesty they nearly defy analysis. Adele Exarchopoulos’ Adele and Lea Seydoux as her lover Emma get so seamlessly inside their characters that it’s impossible to see their technique. They really are Adele and Emma (in an unprecedented move, they shared the Palm d’Or with the director) who come together, love, and part ways, summoning up every uncomfortable emotional pit stop along the way. Yet for a film that touches every base of the “boy meets girl” formula (albeit “girl meets girl” here) Blue is the Warmest Color climbs cinematic peaks rarely reached before. Again, it is the telling not the tale that makes all the difference. By collecting the mundane personal details of Adele’s life as well as her revelations, director Kechiche creates one of the most richly-etched character studies in recent film history.

We meet Adele as she’s rushing to high school in her junior year, just a tad late. She’s a little ruffled, but Adele always seems a little off-balance, unsure of her instincts and often struck dumb by the unexpected. The unexpected comes when she finds herself suddenly hypnotized by a blue-haired butch art student she spots in town. The film is knee-deep in naturalistic rhythms and fly-on-the-wall camerawork, but the first time Adele spots Emma is like Tony and Maria’s meeting in West Side Story; all sounds fade out with only the ringing of a street musician’s steel drums and Adele’s breathing heard as she watches Emma walk past, her arm thrown loosely around another woman. The image of her haunts Adele’s dreams until she finally seeks Emma out at the local lesbian bar.

In so much of the film Adele is seen alone in close-up in the center third of the image’s wide screen, but during sex Adele expands to take up the entire horizontal expanse, as if the sex has strengthened her and made her whole. The film’s sex scenes are what has gotten the most attention and they do carry a taste of reality missing in the choreographed coupling found in most films. There are four extended scenes that portray sex between Adele and Emma, each one like a season in the lifetime of the affair, from the ravenous first time to the more intimate summer of their love to the desperate flailing of the final encounter.

Outside of the bedroom, Adele’s inexperience makes her seem a half-formed soul. With her older partner finding a growing success with her art, Adele finds herself overshadowed in her role as the adoring coltish lover. Adele has few confidants in the film; when things fall apart for her it is only to the camera that she silently reveals herself, her endlessly expressive face finding it impossible to conceal her feelings. The camera finally closes its eyes to Adele at the end of three hours and it leaves us with the gnawing feeling that we’ve abandoned a friend just when she needed us the most. It’s the kind of perfectly unsettled ending, like Rhett leaving Scarlett or Antoine Doinel’s freeze frame in 400 Blows, that makes a film linger in your mind and your emotions for a lifetime.