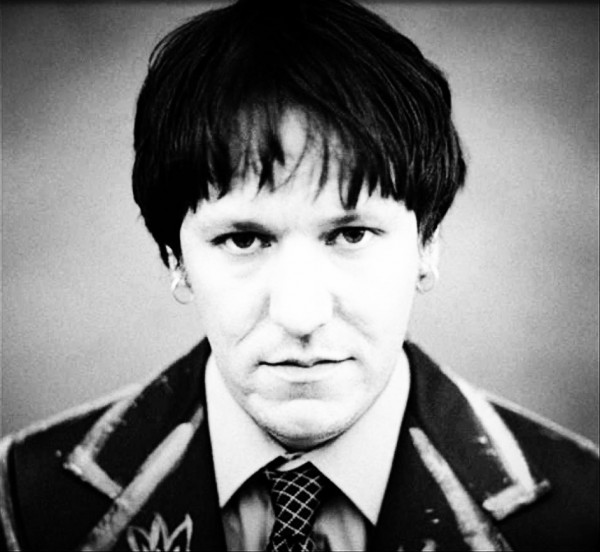

Photo by AUTUMN DE WILDE

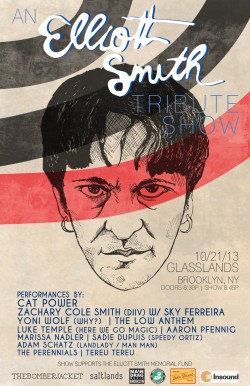

EDITOR’S NOTE: Elliott Smith died 10 years ago today. In remembrance, we are re-running this piece that was originally published in the pages of MAGNET MAGAZINE back in 2004.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Something terrible happened on the night of Oct. 21, 2003, in the cozy, box-like bungalow at 1857 1/2 Lemoyne Street in the Echo Park section of Los Angeles where Elliott Smith lived with girlfriend Jennifer Chiba. In Chiba’s version of events, the couple had an argument that grew so heated she locked herself in the bathroom. At some point, she heard Smith scream and unlocked the door to see him standing with his back to her. When he turned around, there was a knife sticking out of his chest and he was gasping for breath. Panicked, Chiba pulled the knife out of him, and Smith turned and took a few steps before collapsing. Chiba called 911, and an operator talked her through CPR until the paramedics arrived. Smith was rushed to a nearby hospital, where emergency surgery to repair the two stab wounds to the heart couldn’t save his life.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Something terrible happened on the night of Oct. 21, 2003, in the cozy, box-like bungalow at 1857 1/2 Lemoyne Street in the Echo Park section of Los Angeles where Elliott Smith lived with girlfriend Jennifer Chiba. In Chiba’s version of events, the couple had an argument that grew so heated she locked herself in the bathroom. At some point, she heard Smith scream and unlocked the door to see him standing with his back to her. When he turned around, there was a knife sticking out of his chest and he was gasping for breath. Panicked, Chiba pulled the knife out of him, and Smith turned and took a few steps before collapsing. Chiba called 911, and an operator talked her through CPR until the paramedics arrived. Smith was rushed to a nearby hospital, where emergency surgery to repair the two stab wounds to the heart couldn’t save his life.

Back at the house, police found a note written on a Post-It:

I’m so sorry.

Love, Elliott

God forgive me.

When the coroner’s report was finally issued in January 2004, the nature of Smith’s death was maddeningly ambiguous. While the circumstances of the case had most of the hallmarks of a suicide, certain factors also pointed to the possibility of a homicide: the absence of hesitation wounds (the nicks and cuts that come from tentative initial attempts to stab yourself), the fact that Smith didn’t remove his shirt before stabbing himself, a pair of cuts on his hand and arm that could’ve been defensive wounds incurred while fighting off an attacker. There’s also Chiba’s removal of the knife and what police characterize as her refusal to cooperate with investigators, all of which leaves the precise nature of Smith’s death in limbo. Chiba has since refuted police reports that she didn’t cooperate, but the case remains officially open and under investigation.

I don’t pretend to have known Elliott Smith, but I spent about a week with him on the road and at his home when I was profiling him for a MAGNET cover story four years  ago. At the tail end of a tour in support of 2000’s Figure 8, he looked tired and thin. His long hair, unwashed for days, framed his ravaged face. I wrote that he looked like Christ after three days on the cross. A bit dramatic, perhaps, but no less accurate. He played me a new song he’d just recorded. The irony of the title is tragic bordering on the grotesque. He told me it was called “A Dying Man In A Living Room,” but it would eventually turn up on 2004’s posthumous From A Basement On The Hill (Anti-) with the title “A Fond Farewell.”

ago. At the tail end of a tour in support of 2000’s Figure 8, he looked tired and thin. His long hair, unwashed for days, framed his ravaged face. I wrote that he looked like Christ after three days on the cross. A bit dramatic, perhaps, but no less accurate. He played me a new song he’d just recorded. The irony of the title is tragic bordering on the grotesque. He told me it was called “A Dying Man In A Living Room,” but it would eventually turn up on 2004’s posthumous From A Basement On The Hill (Anti-) with the title “A Fond Farewell.”

Smith’s childhood was rough, a fact underscored by his unwillingness to talk about it. “There’s not much I could say about that time that I would like to see in print,” he said. “I wouldn’t want to remind any of the people involved of that time.”

Smith’s parents split when he was a year and a half; he grew up with his mother and stepfather in the suburbs of Dallas, where he was preyed upon by schoolyard bullies and, later, hassled by the police. He left Texas when he was 14 to live with his father in Portland, Ore., claiming he feared for his mother’s safety. In the last few years of his life, he confessed to close friends that he was tormented by vague memories of sexual abuse back in Dallas. Shortly before he died, Smith established a charity for abused children to which he planned to funnel all the royalties from Basement On The Hill. (In the wake of his death, his family has since softened the name from the Elliott Smith Fund for Abused Children to the Elliott Smith Memorial Fund.)

In his early 20s, during the flannel glory days of the early-’90s Pacific Northwest, Smith played guitar in a Portland grunge outfit called Heatmiser. After three albums, he quit the band because, he often said, when you grow up around a lot of yelling and screaming, the last thing you want to do is be in a band where everyone’s yelling and screaming. He struck out on his own, making music that was the polar opposite of grunge: delicately acoustic, painfully introspective, full of flickering-candle reverie and blurred visions of personal disintegration, betrayal and heartbreak. With each album, his audience grew, swelling with legions of crushed romantics, the desperately lonely and the clinically sad.

Yet even as Smith’s profile rose—in 1998 he was nominated for an Academy Award for “Miss Misery,” from Gus Van Sant’s Good Will Hunting—he was collapsing inside. He seesawed up and down between drug use and alcoholism, full-blown depression and tenuous recovery. Friends staged interventions. There were hospitalizations. At some point, he told me, aided by Paxil, he simply willed himself back into the light with this personal mantra: Things are going to work out, and I am never going to stop insisting that things are going to work out. On the last day I spent with Smith, we sat outside his bungalow, tucked away in a leafy section of Silver Lake. I asked him a lot of pretentious, big-picture questions about love and death and God. At one point, I asked him if he thought suicide was courageous or cowardly.

“It’s ugly and cruel and I really need my friends to stick around, but dying people should have that right,” he said. “I was hospitalized for a while and I didn’t have that option, and it made me feel even crazier. But I prefer not to appear as some kind of disturbed person. I think a lot of people try to get mileage out of it, like, ‘I’m a tortured artist’ or something. I’m not a tortured artist, and there’s nothing really wrong with me. I just had a bad time for a while.”

From A Basement On The Hill isn’t the last will and testament of Elliott Smith. Alas, that is unknowable, hidden behind a protective wall of silence erected by his family and friends. To try and scale it is a fool’s errand; take it from someone who was fool enough to care and crass enough to try. The true facts of his life are beyond our privilege, beyond our right to know, perhaps correctly so. Maybe that will be one of Smith’s legacies: that the integrity with which he created his art and the decency with which he treated those around him will forever guard the purity of his memory. MORE

PREVIOUSLY: Near the end of The Royal Tenenbaums, Wes Anderson’s storybook cinematic fable of wasted potential, the character of Richie, a disgraced world-class tennis player with a dark secret, looks soulfully into the bathroom mirror. It’s impossible to say what he’s thinking–he looks scared, confused, angry, on the verge. A tensely strummed acoustic guitar spirals in the background, accompanying a hushed, faintly ominous vocal. It’s Elliott Smith’s “Needle in the Hay.” Richie picks up a scissors and methodically, if crudely, crops his shoulder-length tresses down to the scalp. He lathers up his lumberjack beard and shaves it clean. He stares hard in the mirror, unblinking, trying to recognize the face he sees. The music swells, whispery and unnerving. He nods slightly, pops the blade out of the razor and slashes his wrists. In the end, Richie Tenenbaum is saved. Elliott Smith was not. Last week he was found in his apartment in Los Angeles, dead from a self- inflicted knife wound to the chest. Sad to say, deep down nobody who knew him is really all that surprised. He lived in an orbit of despair, and he bore all the usual scars: inconsolable depression, unshakeable addictions, suicidal tendencies. He was not a pretty man, but his music could win beauty contests. Over the course of five albums, he managed to channel a profound sadness into aching, velveteen folk-rock carols. The best of them sound like mercy itself. MORE

RELATED: In the December 2004 issue of SPIN, we published Los Angeles journalist/musician Liam Gowing’s detailed, empathetic look at the last years of Elliott Smith’s life and the circumstances that led up to the Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter’s apparent suicide. “Mr. Misery” was difficult to read, a tremendous challenge to edit and fact-check, and one of the most remarkably intimate pieces in the magazine’s history. On the 10th anniversary of Smith’s death, it’s now available for the first time on the site. MORE

Elliott Smith – Waltz #2 (XO) from Bowsprit on Vimeo.

RELATED: “Waltz #2 (XO),” the third song on XO (1998), is Elliott Smith’s certain masterpiece. It’s got a roadhouse, Wild West, player-piano feel to it. And the tune, with its staccato ¾ beat, takes Smith back to Cedar Hill, the suburbs of Texas with his mother, Bunny, and stepfather, Charlie. There’s love in “Waltz #2 (XO),” but a deeper impulse is anger, aimed squarely at Charlie. Brilliantly laid out in metaphorical cloakings, the song’s a secret life history, summarizing Elliott’s feelings about the Cedar Hill atmosphere and the intricacies of his relationship with mother and stepfather. He was always exceptionally worried about the possible hurtfulness of his lyrics. The thought that they might cause harm pained him. So a habit was established according to which he’d begin songs directly, explicitly autobiographically, then revise away from fact toward vagueness and abstraction. Choice specifics grounded the song, but meanings trailed off into obscurity. Emotionally, it was an elision of the personal—there but camouflaged—a self-erasure. He was in the songs, they were him, it was his personal past reconsidered, the sum total of who he was, but they were more too, a mix of voices, first, second, and third person, all getting a word in, all with something crucial to say. “XO,” as Smith told an interviewer in 1998, means “hugs and kisses,” the sort of thing people throw in at the end of letters. A more arcane, connotative meaning was “fuck off.” “But that’s a really rare meaning I didn’t know about,” Elliott explains, apparently sincerely. “Waltz #2 (XO)” kicks off with a hard, blunt beat, followed by vaguely ominous-sounding, A-minor guitar chords. Piano enters—that saloon vibe Elliott always enjoyed, even from Cedar Hill days. The setting is a karaoke bar. Bunny sings the Everly Brothers tune “Cathy’s Clown” (“He’s not a man at all … Dontcha think it’s kinda sad/ that you’re treating me so bad/ or don’t you even care?”), a possible allusion to Charlie, whom Elliott had seemed to link with clowns in other songs too. He can’t read her expression. She just stares off into space. What Elliott notices—the Charlie subcurrent—she does not. But his feelings for her are obviously positive. He vows, “I’m never going to know you now/ but I’m going to love you anyhow.” MORE