FRESH AIR

![]()

In his new book The Everything Store, Brad Stone chronicles how Amazon became an “innovative, disruptive, and often polarizing technology powerhouse.” He writes that Amazon was among the first to realize the potential of the Internet and that the company “ended up forever changing the way we shop and read.” Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos holds up the Kindle Fire HD in two sizes during a press conference in Santa Monica, Calif., in September 2012.Amazon started off selling books, but Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and CEO, always had the intention of turning it into an online market that sold everything. In the process of becoming “an everything store,” Amazon acquired many other dot-coms including Zappos and Diapers.com, and expanded into selling web services as well. Bezos owns a rocket company, called Blue Origin and in August he invested in old media, purchasing The  Washington Post for $250 million.Bezos himself is the 12th richest person in the U. S., with a fortune estimated at $25 billion. Stone, a senior writer for Bloomberg Businessweek, has covered Amazon and technology in the Silicon Valley for 15 years. His book draws on interviews he conducted with Bezos over the years as well as interviews with more than 300 current and former Amazon executives and employees. MORE

Washington Post for $250 million.Bezos himself is the 12th richest person in the U. S., with a fortune estimated at $25 billion. Stone, a senior writer for Bloomberg Businessweek, has covered Amazon and technology in the Silicon Valley for 15 years. His book draws on interviews he conducted with Bezos over the years as well as interviews with more than 300 current and former Amazon executives and employees. MORE

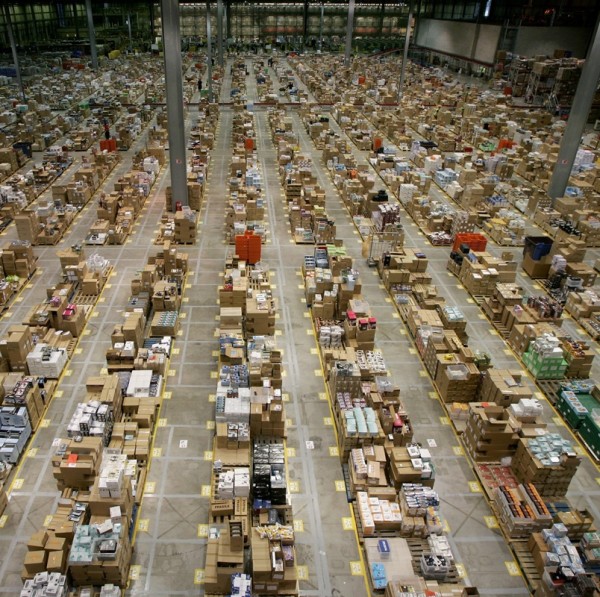

RELATED: I decided to get a job working in the Amazon warehouse solely for the purpose of unionizing it. No one asked me to do it. No one paid me. I took the task on out of a newfound zeal and a belief in what unionizing could do. Up until then my ideas about unions were vague. I was pro-union in orientation, not experience. I had seen John Sayles’ Matewan and knew that “Solidarity Forever” was a song, but that was about it. What ideas I did have were steeped in nostalgia and rooted in a desire for working class authenticity. I found ethical simplicity of a world in which the boss is the guy in the office, and the worker is the guy in the coal pit very appealing, but it wasn’t all that relevant. But the Teamsters and the Longshore had something we didn’t, the mystique of the blue-collar worker. Like most of my generation, I made my living in the service industry. We worked, sure, but we weren’t ‘workers.’ Somehow, our shiny tech world was exempt from class struggle. Our economy depended on market speculation. It revolved around saleable ideas, stock options and vesting. People at Microsoft and Amazon were walking away with hundreds of thousands of dollars after two or three years. By fall of 1999, though, fewer and fewer people were getting lucky and jobs were growing scarce. If you wanted in to Microsoft, you had to spend years temping with rolling layoffs. And if you did get in, you better not complain. ‘Be grateful you have a job’ became the new mantra. Besides, your manager probably listens to Sonic Youth and won’t care if your hair is green-isn’t that enough? […]

Today, I think Amazon probably did know about me, and that what they knew was that I was essentially harmless. I was more valuable for my production speed than dangerous for my organizing. But to make the case that Amazon is anti-union barely approaches relevance. Most companies are anti-union, that’s not important right now. What made Amazon unique was the way in which it was. Bezos once bragged in a Wall Street Journal interview that he told temp agencies to hire the “freaks.” The assumption at the time was that Bezos wanted creativity. But his creative staff wasn’t coming out of the temp agencies, the warehouse recruits were. And I never met a “freak” who wouldn’t throw over a decent wage to work somewhere lousy if they felt they belonged. These were people who wanted to be a part of something. They wanted to be valued for who they were, rather than what they produced. I often wondered if what Bezos really figured out was that if you gave freaks a home, they would give you everything they had-their best ideas, their longest days, and their rights on the job. And that’s what they did. MORE