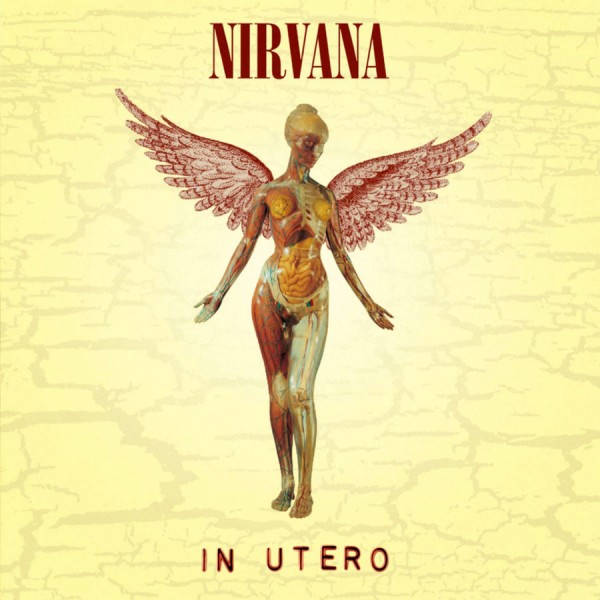

SPIN: As they did with the Nevermind re-release two years back, Universal’s reissue department has dug deep and served up everything worth a sniff, with predictably mixed results. It’s all collected into the overstuffed “Super Deluxe” edition, which at press time cost around $125 on Amazon: a remastered version of the original album; a new “2013 mix” by producer Steve Albini; assorted B-sides, outtakes, demos and alternate mixes; the staggeringly great Live & Loud set from December 1993 (appearing on both CD and DVD); and a lavish booklet containing reproductions of Cobain’s handwritten lyrics, photos from the sessions, a short reminisce from comedian Bobcat Goldthwait (the tour’s opening act), and a fascinating 1992 four-page fax from Albini laying out his proposal and expectations for the sessions…The fax from Albini included in the booklet concludes with a PS: “If a record takes more than a week to make, somebody’s fucking up. Oi!” They ended up taking 10 days to make this, Nirvana’s final studio album. For many fans, there’s a dark cloud over In Utero, and even minus all the baggage, it’s probably few people’s favorite, if only because of what came after. MORE

PREVIOUSLY: About A Boy

PREVIOUSLY: THE COLONEL REMEMEBERS: Nirvana @ JC Dobbs

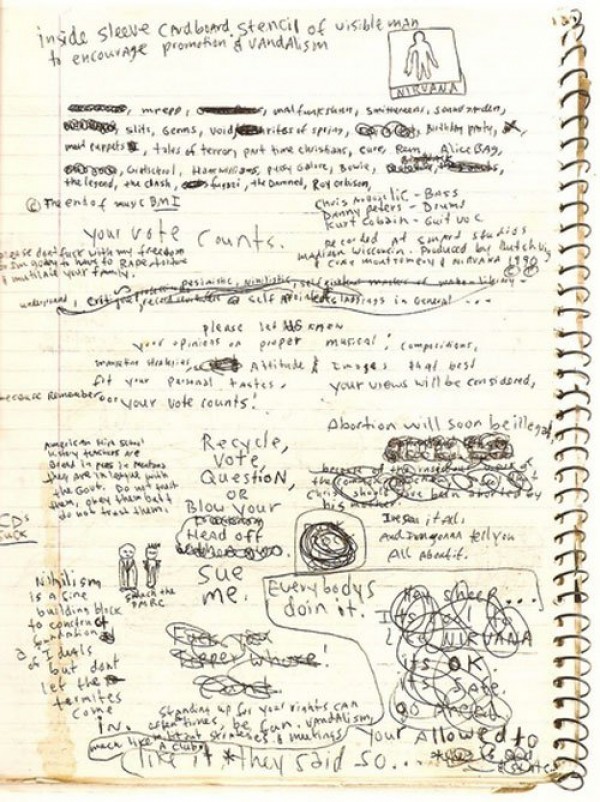

PREVIOUSLY: Here’s a dog-eared road map of the soul of a generational unit shifter, etched into the bas relief of a spiral-bound notebook. It includes Kurt-penned comic strips, a list of things to do to become a famous rock band and the standard piss-and-moan rants against prog-rock and the sexist-homophobic-football-loving-gun-toting-white-male-corporate hegemony. In other words, it’s the last will and testament of this self-described Pisces Jesus Man marking his passage through the various stations of the rock ‘n’ roll cross. In the end nobody is saved, except Courtney Love’s bank account and rock ‘n’ roll–for a few minutes, anyway. Because if Kurt Cobain came back today and saw what was being done in his name, he would never stop vomiting. In my fantasy, I take this book to a Creed concert, open it up and a ray of blinding white light shoots out and smites the band into dust. — JONATHAN VALANIA

PREVIOUSLY: Sometime between Bleach and Nevermind, Kurt Cobain repurposed the Pixies’ patented lulling verse/volcanic chorus dynamic to prop up the enormous chip on his shoulder during the Frankenstein-ish  gene-splicing experiments with the Beatles and Black Sabbath he was conducting out in rainy Seattle. The monster would, of course, rise from the slab and kill its creator in the end. In 1994, when Cobain bit down on the barrel of a 20-gauge shotgun and pulled the trigger, he killed a lot of birds with one stone. He widowed his wife and essentially orphaned his daughter, his art and an entire generation of disciples who hung on his every word. He also managed to freeze-frame his legacy into the hallowed halls of martyrdom, ensuring that every future assessment of his work would be filtered through the grim prism of his self-inflicted crucifixion. Doled out by the keepers of his flame to re-up the visitorship to the shrine of St. Kurt, With the Lights Out is a four-disc barrel-bottom-scraping time capsule of his electrifying tantrums and territorial pissings, and when he felt like it, his seemingly bottomless capacity for heart-shaped melodicism. There are three moments on this collection of 80-some tracks that make the hair on the back of my neck stand up: a demo version of “Rape Me” with a newborn Francis Bean Cobain crying throughout; a solo acoustic reading of “All Apologies” that has the same angel-wing flutter of John Lennon’s acoustic demo of “Strawberry Fields Forever”; and a filmed segment of the band in a Brazilian recording studio performing Terry Jacks’ maudlin ’70s soft-rock meisterwork “Seasons in the Sun”–with Cobain on drums, Dave Grohl on bass and Krist Novoselic on guitar–interspersed with home movie footage of the band members in younger days having joy and having fun, despite the growing sense that the hills they climbed were just seasons out of time. Much of this material–home demo tapes, radio station performances and early acoustic versions of classic Nirvana tracks–has long been traded in the shadowy digital chop shops of file-sharing networks, but the true value in this enterprise is that, as you read this, a runny-nosed kid eating Froot Loops out of a dirty bowl in some flea-bitten double-wide in Cow’s Ass, Ind., is listening to With the Lights Out and realizing he can purge all his rage, self-loathing and ham-fisted fumbling for grace into three serrated guitar chords and a primal yowl. And one day he–or for that matter, she–will change music once again.

gene-splicing experiments with the Beatles and Black Sabbath he was conducting out in rainy Seattle. The monster would, of course, rise from the slab and kill its creator in the end. In 1994, when Cobain bit down on the barrel of a 20-gauge shotgun and pulled the trigger, he killed a lot of birds with one stone. He widowed his wife and essentially orphaned his daughter, his art and an entire generation of disciples who hung on his every word. He also managed to freeze-frame his legacy into the hallowed halls of martyrdom, ensuring that every future assessment of his work would be filtered through the grim prism of his self-inflicted crucifixion. Doled out by the keepers of his flame to re-up the visitorship to the shrine of St. Kurt, With the Lights Out is a four-disc barrel-bottom-scraping time capsule of his electrifying tantrums and territorial pissings, and when he felt like it, his seemingly bottomless capacity for heart-shaped melodicism. There are three moments on this collection of 80-some tracks that make the hair on the back of my neck stand up: a demo version of “Rape Me” with a newborn Francis Bean Cobain crying throughout; a solo acoustic reading of “All Apologies” that has the same angel-wing flutter of John Lennon’s acoustic demo of “Strawberry Fields Forever”; and a filmed segment of the band in a Brazilian recording studio performing Terry Jacks’ maudlin ’70s soft-rock meisterwork “Seasons in the Sun”–with Cobain on drums, Dave Grohl on bass and Krist Novoselic on guitar–interspersed with home movie footage of the band members in younger days having joy and having fun, despite the growing sense that the hills they climbed were just seasons out of time. Much of this material–home demo tapes, radio station performances and early acoustic versions of classic Nirvana tracks–has long been traded in the shadowy digital chop shops of file-sharing networks, but the true value in this enterprise is that, as you read this, a runny-nosed kid eating Froot Loops out of a dirty bowl in some flea-bitten double-wide in Cow’s Ass, Ind., is listening to With the Lights Out and realizing he can purge all his rage, self-loathing and ham-fisted fumbling for grace into three serrated guitar chords and a primal yowl. And one day he–or for that matter, she–will change music once again.

‘Tis the season, so let’s end with a bit of blasphemy: The loss of Elliott Smith is far more significant than the loss of Kurt Cobain. There. I said it. Both were immensely talented, deeply troubled souls not long for this world. Profoundly bruised on the inside, both earned the right to spend their time on earth doing the backstroke in the deep wells of self-pity. The crucial difference is that Smith’s fall-back position was beauty, no matter how ugly he felt on the inside, and that will lend his songbook a far lengthier shelf life. Cobain’s fall-back position was always ugliness–I hate myself and I want to die, and this is what that sounds like–and maybe one day all his angry noise will mellow into fine whine, like, say, White Light/White Heat-era Velvets. But 10 years A.D., a lot of it just seems to be rusting out in the weeds alongside unsold copies of the last Love Battery album. Quoting Neil Young in his suicide note, Cobain noted that it’s better to burn out than fade away. And while that may be true, Neil also pointed out that rust never sleeps. Elliott Smith never slept much, and he too wrote a suicide note, but he set his to pretty music, and it more or less became From a Basement on the Hill. Despite my misgivings that what I’m about to say might be misinterpreted as glorifying suicide, Basement is my hands-down choice for album of the year. Nothing I heard all year came close to matching its unflinching emotional courage, brutal honesty, druggy swoon and, most important, breathtaking beauty. Smith dubbed the sound he was going for in the last years of his life “California frown,” a post-Prozac update of the orange-sunshine whimsy of Wilsonian West Coast pop–sunbeam harmony, hymnal organ, infinite echo and good vibrations–crossed with Plastic Ono Band junkie confessionals that make William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch look like Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Yes, he was trying to break your heart, but the beautiful difference between life and art is that in art, Elliott Smith doesn’t die in the end. — JONATHAN VALANIA

‘Tis the season, so let’s end with a bit of blasphemy: The loss of Elliott Smith is far more significant than the loss of Kurt Cobain. There. I said it. Both were immensely talented, deeply troubled souls not long for this world. Profoundly bruised on the inside, both earned the right to spend their time on earth doing the backstroke in the deep wells of self-pity. The crucial difference is that Smith’s fall-back position was beauty, no matter how ugly he felt on the inside, and that will lend his songbook a far lengthier shelf life. Cobain’s fall-back position was always ugliness–I hate myself and I want to die, and this is what that sounds like–and maybe one day all his angry noise will mellow into fine whine, like, say, White Light/White Heat-era Velvets. But 10 years A.D., a lot of it just seems to be rusting out in the weeds alongside unsold copies of the last Love Battery album. Quoting Neil Young in his suicide note, Cobain noted that it’s better to burn out than fade away. And while that may be true, Neil also pointed out that rust never sleeps. Elliott Smith never slept much, and he too wrote a suicide note, but he set his to pretty music, and it more or less became From a Basement on the Hill. Despite my misgivings that what I’m about to say might be misinterpreted as glorifying suicide, Basement is my hands-down choice for album of the year. Nothing I heard all year came close to matching its unflinching emotional courage, brutal honesty, druggy swoon and, most important, breathtaking beauty. Smith dubbed the sound he was going for in the last years of his life “California frown,” a post-Prozac update of the orange-sunshine whimsy of Wilsonian West Coast pop–sunbeam harmony, hymnal organ, infinite echo and good vibrations–crossed with Plastic Ono Band junkie confessionals that make William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch look like Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Yes, he was trying to break your heart, but the beautiful difference between life and art is that in art, Elliott Smith doesn’t die in the end. — JONATHAN VALANIA