FRESH AIR

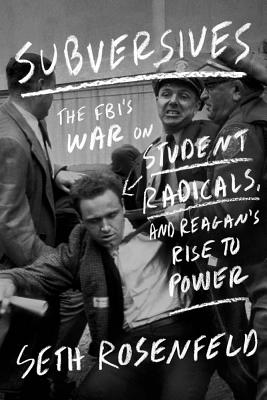

![]() In 1964, students at the University of California, Berkeley, formed a protest movement to repeal a campus rule banning students from engaging in political activities. Then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover suspected the free speech movement to be evidence of a Communist plot to disrupt U.S. campuses. He “had long been concerned about alleged subversion within the education field,” journalist Seth Rosenfeld tells Fresh Air’s Terry Gross. So Hoover ordered his agents to look into whether the movement was subversive. When they returned and said that it wasn’t, Hoover not only continued to investigate the group but also used “dirty tricks to stifle dissent on the campus,” according to Rosenfeld. Rosenfeld’s new book, Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals and Reagan’s Rise to Power, details how the FBI employed fake reporters to plant ideas and shape public opinion about the student movement; how they planted stories with real reporters; and how they even managed — with the help of then-Gov. Ronald Reagan — to get the UC Berkeley’s President Clark Kerr fired. To research the book, Rosenfeld pored over 300,000 pages of records obtained over 30 years from five lengthy Freedom of Information Act lawsuits against the FBI. MORE

In 1964, students at the University of California, Berkeley, formed a protest movement to repeal a campus rule banning students from engaging in political activities. Then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover suspected the free speech movement to be evidence of a Communist plot to disrupt U.S. campuses. He “had long been concerned about alleged subversion within the education field,” journalist Seth Rosenfeld tells Fresh Air’s Terry Gross. So Hoover ordered his agents to look into whether the movement was subversive. When they returned and said that it wasn’t, Hoover not only continued to investigate the group but also used “dirty tricks to stifle dissent on the campus,” according to Rosenfeld. Rosenfeld’s new book, Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals and Reagan’s Rise to Power, details how the FBI employed fake reporters to plant ideas and shape public opinion about the student movement; how they planted stories with real reporters; and how they even managed — with the help of then-Gov. Ronald Reagan — to get the UC Berkeley’s President Clark Kerr fired. To research the book, Rosenfeld pored over 300,000 pages of records obtained over 30 years from five lengthy Freedom of Information Act lawsuits against the FBI. MORE

TRUTH DIG: The protests at UC Berkeley in the 1960s—and the conservative backlash that followed them—helped propel Ronald Reagan to the governor’s mansion and then to the White House. Since then, a generation of conservative adoration has transformed Reagan into the embodiment of Republican virtue. Seth Rosenfeld’s new book, “Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals, and Reagan’s Rise to Power,” challenges that portrait in a unique and compelling way. Drawing on FBI files and scores of interviews, Rosenfeld shows how Reagan formed a partnership with the FBI that began in the 1940s and lasted at least until J. Edgar Hoover’s death in 1972. During that time, Reagan, Hoover and their allies sabotaged the careers of law-abiding citizens, defended reckless police violence and exploited an appalling double standard in the political use of FBI intelligence.

In 1969, riot police shot dozens of Berkeley protesters and bystanders with birdshot and buckshot, permanently blinding one man and killing student James Rector. Reagan told an Orange County audience, “The police didn’t kill the young man. He was killed by the first college administrator who said some time ago that it was all right to break the laws in the name of dissent.” It was a transparent attempt to blame others for the “bloodbath” he had welcomed in an earlier public remark. Even more outrageously, Reagan aide Edwin Meese told journalist (and now Truthdig Editor-in-Chief) Robert Scheer, “James Rector deserved to die,” an opinion he repeated to Rosenfeld. Some deputies were sanctioned for the shootings but none were convicted, and federal charges were dropped after Reagan pressed U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell. The Reagan administration’s policy—“Obey the rules or get out”—seemed to apply only to university students.

With Reagan, of course, the rest is history. In one of his first presidential acts, he pardoned high-ranking FBI officials who had authorized warrantless break-ins at the homes of relatives and friends of Weather Underground fugitives.  In announcing the pardons, Reagan said, “The record demonstrates that they acted not with criminal intent but in the belief that they had grants of authority reaching to the highest levels of government.” One of the prosecutors flatly refuted that claim. “That assertion is false,” Francis J. Martin wrote in a New York Times opinion piece. “The FBI’s own documents attest to the fact that it is false. After an eight-week trial, 12 jurors unanimously found it to be false.”

In announcing the pardons, Reagan said, “The record demonstrates that they acted not with criminal intent but in the belief that they had grants of authority reaching to the highest levels of government.” One of the prosecutors flatly refuted that claim. “That assertion is false,” Francis J. Martin wrote in a New York Times opinion piece. “The FBI’s own documents attest to the fact that it is false. After an eight-week trial, 12 jurors unanimously found it to be false.”

One of the book’s most interesting stories concerns the FBI’s efforts to withhold information about its assistance to Reagan. In an appendix, Rosenfeld details the lawsuits he filed and won over three decades to acquire the relevant FBI documents. The heroes of this saga include San Francisco federal Judge Marilyn Patel, who ruled that “Information regarding acts taken to protect or promote Reagan’s political career, or acts done as political favors to Reagan[,], serve no legitimate law enforcement purpose.” Having studied some 50,000 pages of FBI records, Rosenfeld reaches the following conclusion:

These documents show that during the Cold War, FBI officials sought to change the course of history by secretly interceding in events, manipulating public opinion, and taking sides in partisan politics. The bureau’s efforts, decades later, to improperly withhold information about those activities under the [Freedom of Information Act] are, in effect, another attempt to shape history, this time by obscuring the past. MORE

RELATED: In the early 1960s Reagan opposed certain civil rights legislation, saying that “if an individual wants to discriminate against Negroes or others in selling or renting his house, it is his right to do so.”[67] In his rationale, he cited his opposition to government intrusion into personal freedoms, as opposed to racism; he strongly denied having racist motives and later reversed his opposition to voting rights and fair housing laws.[68] When legislation that would become Medicare was introduced in 1961, Reagan created a recording for the American Medical Association warning that such legislation would mean the end of freedom in America. Reagan said that if his listeners did not write letters to prevent it, “we will awake to find that we have socialism. And if you don’t do this, and if I don’t do it, one of these days, you and I are going to spend our sunset years telling our children, and our children’s children, what it once was like in America when men were free.”[69][70][71] He also joined the National Rifle Association and would become a lifetime member.[72]