THE BLING RING (2013, directed by Sofia Coppola, 90 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC It’s hard to imagine any film involving Paris Hilton would grab my attention but Sofia Coppola found the angle with her latest, The Bling Ring. Based on a series of celebrity home burglaries carried out in 2008 and 2009 by fashion-conscious teens, one might expect a dreamy joyride through the perverse luxury of the glamor class. If robbing Hilton’s underwear drawer sounds like a good time at the movies, Ms. Coppola’s perspective is different: she sees these reckless kids not as joyriders but as the unwashed hordes climbing over the castle walls. The Bling Ring is a film made by a woman who despises her subjects, a dismissive hate letter fired across the bough of class, and unsurprisingly, it is a bit of a drag to sit through.

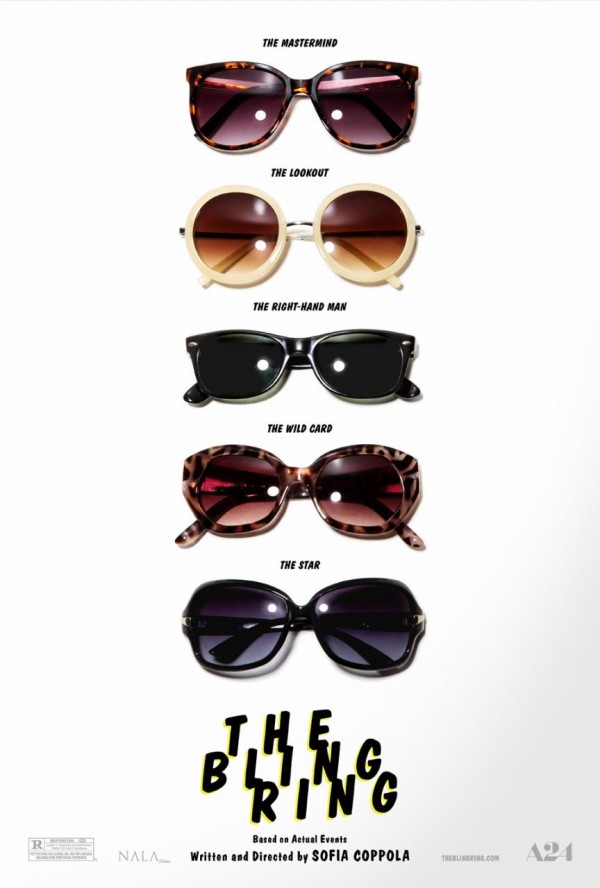

Coppola shows most empathy for the one male in the posse, the dough-eyed Marc (newcomer Israel Broussard,) a slightly-dim, closeted Clyde who meets his Bonnie when transferring to a new high school. She’s an icy dragon lady named Rebecca (Kate Chang) who doesn’t flinch for a second to commit petty burglaries. It’s Rebecca who comes up with idea of breaking into stars homes, and when she can finally tear Marc away from TMZ, he looks up Paris Hilton’s address and itinerary for their first “sneak and snatch” crime.

The trio of friends they bring with them are the ones for which Coppola really unleashes her poison darts, Nicki (Emma Watson) and Chloe (Clair Julien) and their adopted sister Sam. (Taiisa Farmiga.) The characters themselves are interchangeable, empty vessels of bitter put-downs, nihilistic greed, and nakedly insincere tributes. The scene with their batty mother is the film’s most broadly satiric. Leslie Mann plays Laurie like a suburban witch with her coven. Wide-eyed and glibly upbeat, Laurie home schools the bored sisters, basing her teachings on a philosophy gleaned from Rhoda Byrne’s “positive thing” bestseller The Secret. “What qualities do you most admire in Angelina Jolie?” she asks them, “Her bitchin’ bod.” they mockingly answer. Seems like nothing is sacred for these girls, except club-hopping and wearing pants that make their asses look good.

Coppola’s métier is character study, especially of the malaise of the privileged class. Here, a little further down the economic food-chain, she has flattened the character’s down to celebrity media-obsessed glamor zombies. Coppola’s disdain for her subjects runs so deep for these teens that she can’t allow them to revel in the stolen luxury. The break-ins are shown clinically, often from a distance that keeps us too far back to enjoy any giddy thrills. In the clubs the gang is too self-conscious about being seen to really enjoy themselves and their one triumphant joyride is quickly cut short by a car plowing into their side. Stealing from the rich has never before seemed like such a downer.

That is part of the unexplored ambivalence at the heart of the film. While absconding with $3 million worth of clothes and cash may not be a victimless crime, it hardly seems like it will be missed by the likes of Megan Fox and Lindsey Lohan, nor does it bring up thoughts like “Hey, Paris Hilton worked hard for those shoes!” Their Hollywood Hills estates are presented less like personal homes than museums of absurd wealth, and who could abide by museums visitors getting sticky-fingered with the artifacts? At the film’s end, title cards announce the sentences the characters served in government confinement. A final reminder to anyone getting ideas, if you try to touch the ruby slippers, prepare for a nasty shock.