The year is high in the mid-’60s. The place: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, a country chafing under a brutal dictatorship. The setting: a swingin’ ’60s nightclub au-go-go straight out of Austin Powers. Lights flash and the music throbs as the camera zooms in and out to the beat. The club is filled with the hip, the young and the privileged, all dressed in mod Carnaby Street finery. Os Mutantes, Brazil’s rough-translation answer to the psychedelic-period Beatles, are set to take the stage. Suddenly, the music cuts out and the lights come up as the room fills with government storm troopers.

The soldiers, members of the dreaded CCC (Communist Hunt Command), begin brutalizing the crowd, making arrests and conducting interrogations. The members of Os Mutantes escape out the back door. Such was life in Brazil in the ’60s, where simply plugging in an electric guitar was a revolutionary act.

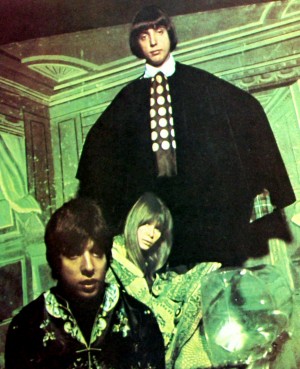

Inspired by the Beatles and smuggled-in news of the burgeoning counterculture in Britain and America, Os Mutantes was formed in 1966 by the Baptista brothers–singer-songwriter-bassist Arnaldo and 15-year-old guitarist Sergio –and singer Rita Lee. The music was a glorious sunshine super bossa nova–Starburst guitar psychedelia, warped samba, gossamer harmonies, and the strange bells and whistles of theremins, Moogs and a host of homemade instruments and effects pedals.

In their day, Os Mutantes sounded nothing short of radical, especially given the repression under which they operated. Electric guitars and effects pedals, nearly impossible to find in Brazil at the time, had to be smuggled into the country. What they couldn’t smuggle in, they made themselves. Os Mutantes relied on the electronic wizardry of the eldest Baptista brother, Claudio, “the fourth Mutante,” who cobbled together devices to recreate the sounds heard on Beatles and Jimi Hendrix records.

Failing that, the band would improvise, sometimes using a can of bug spray to replicate the sound of a hi-hat cymbal. The modern feel of these recordings can be attributed to producer Manoel Barenbein, Brazil’s George Martin, and arranger Rogério Duprat, a disciple of John Cage. At the same time, a cornucopia of pot and psychedelics contributed to the inspired lunacy of these recordings and the band’s eccentric mindset.

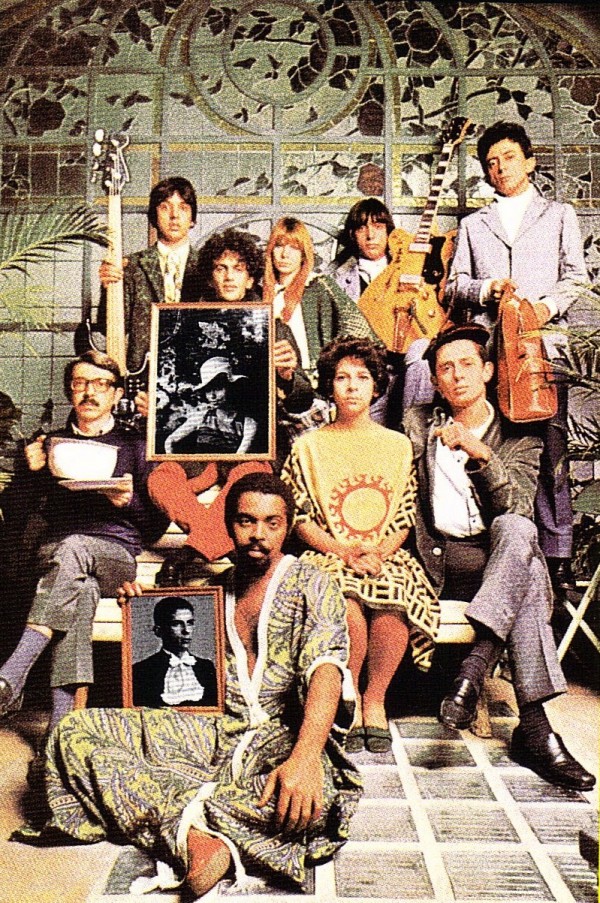

Os Mutantes were immediately embraced by the then-flowering Tropicalia movement, an arty collective of intellectuals, poets and musicians that included Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso and Tom Zé [PICTUED, BELOW]. The Tropicalistas were attempting to cast off the shackles of Brazil’s cultural conservatism and political repression with outré art, music, fashion and ideas.

Os Mutantes were immediately embraced by the then-flowering Tropicalia movement, an arty collective of intellectuals, poets and musicians that included Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso and Tom Zé [PICTUED, BELOW]. The Tropicalistas were attempting to cast off the shackles of Brazil’s cultural conservatism and political repression with outré art, music, fashion and ideas.

It was the Tropicalistas who encouraged Os Mutantes’ controversial appearance at the 1967 Festival of Brazilian Pop Music–the South American equivalent of Dylan going electric at the Newport Folk Festival. In response to the Tropicalistas and other perceived subversives, the Brazilian government passed Institutional Act Five, granting itself the power to arrest and interrogate anyone suspected of being “unpatriotic.” By 1968, Veloso and Gil had been arrested and Os Mutantes went into hiding, until Lee’s father, a dentist at the American embassy, intervened on their behalf.

It was the end of the Tropicalia movement, yet the beginning of Os Mutantes’ recorded legacy. Releasing their eponymous debut in ’68, Os Mutantes would continue to record until 1972, when Lee was asked to leave. While the Baptista brothers soldiered on for a few more albums of ponderous prog-rock wankery, Lee went on to become a major dance music star in Brazil.

A far less glittery fate would await Arnaldo. In December of 1983, he was committed to a mental institution after attacking his mother and jumping out of a third-story window. Kurt Cobain tried unsuccessfully to get Os Mutantes to reunite when Nirvana toured Brazil. In 1999, Luaka Bop issued a best-of compilation, Everything Is Possible. House label Om Platten reissued the first three proper albums: Os Mutantes, Mutantes and the Divina Comedia Ou Ando Meio Desigado. — JONATHAN VALANIA