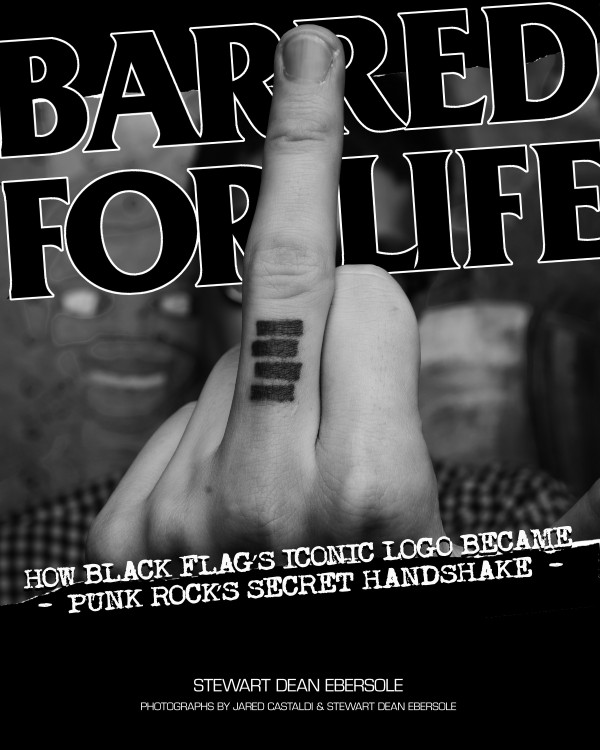

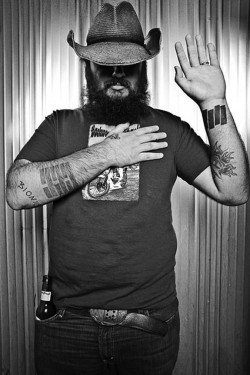

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Perhaps you’ve seen Stewart Ebersole [PICTURED BELOW, RIGHT] bike messenger-ing around town over the years. He no longer lives in Philadelphia but for many years he cut a pretty dashing profile, a tall drink of water with the gift of gab and miles of style, always changing up his look, sometimes a mod, sometimes a rocker, sometimes shaggy-haired, bearded and Rapsutin-like, but always a punk. Always. Black Flag is his brand, having cut his punk rock teeth back in the early ’80s as a mohawked college radio DJ, and he’s a lifer. He’s got the Black Flag ‘bars’ logo tattooed on his lower leg. Over the years he met a lot of people inked with the Black Flag bars. Young and old. From near and far. Slowly but surely it occurred to him that the bars tattoo was the secret handshake of punk rock. Six years ago he embarked on an improbable odyssey: to meet, interview and photograph as many people around the world with the Black bars tattoo as he could and publish a book about it. Earlier this month, after hundreds of man hours and thousands of miles traveled, he published BARRED FOR LIFE. Stewart will be in town Sunday to celebrate the publication of the book at Tattooed Mom’s on South Street from 7-10. Show your bars to the bartender for a deep discount on drinks. We got him on the horn from his current home in upstate New York where he currently resides.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Perhaps you’ve seen Stewart Ebersole [PICTURED BELOW, RIGHT] bike messenger-ing around town over the years. He no longer lives in Philadelphia but for many years he cut a pretty dashing profile, a tall drink of water with the gift of gab and miles of style, always changing up his look, sometimes a mod, sometimes a rocker, sometimes shaggy-haired, bearded and Rapsutin-like, but always a punk. Always. Black Flag is his brand, having cut his punk rock teeth back in the early ’80s as a mohawked college radio DJ, and he’s a lifer. He’s got the Black Flag ‘bars’ logo tattooed on his lower leg. Over the years he met a lot of people inked with the Black Flag bars. Young and old. From near and far. Slowly but surely it occurred to him that the bars tattoo was the secret handshake of punk rock. Six years ago he embarked on an improbable odyssey: to meet, interview and photograph as many people around the world with the Black bars tattoo as he could and publish a book about it. Earlier this month, after hundreds of man hours and thousands of miles traveled, he published BARRED FOR LIFE. Stewart will be in town Sunday to celebrate the publication of the book at Tattooed Mom’s on South Street from 7-10. Show your bars to the bartender for a deep discount on drinks. We got him on the horn from his current home in upstate New York where he currently resides.

PHAWKER: Why don’t you explain the concept of the book?

STEWART EBERSOLE: In short, it’s a collection of photographs and interviews with people from all over the world that have the Black Flag bars tattoo.

PHAWKER: Explain the tattoo. How it came about, what it means, etc.

STEWART EBERSOLE: The bars are four slightly offset rectangles, they are close to one another but as they progress from left to right, they’re high low, high low, to create the image of a waving flag. Historically the Black Flag was used as the pirate flag, that was probably from the 1500s all the way to the 1900s, then the anarchists took it over, not like people hell bent on destroying things but the anarchist political movement of the early 20th Century, they picked it up as their flag. In the late ‘70s Black Flag was called Panic, and they were looking for a new logo and new name and [band leader] Gregg Ginn’s brother Raymond Pettibon came up with the design based on the cover art for a book called The Black Flag of Anarchism which is sort of the ABC’s of what anarchism is and had the Black Flag name attached to it, at that time Black Flag was a roach spray. They were about to be sued by a band in the UK who called themselves Panic first, so they changed the name to Black Flag, and they already had the readymade logo.

PHAWKER: So what made you want to do this?

PHAWKER: So what made you want to do this?

STEWART EBERSOLE: Originally it started as a joke amongst friends who all had the Black Flag bars tattooed on them. I’d say since Black Flag broke up in 1986, I’ve probably known about 25 or 30 people with the tattoo, and zero of those 25 or 30 people don’t have issues with their tattoo — fading, white blotches, bars running together etc. — so when I met up with four or five of my friends in Columbus, Ohio in 2006, to get a touch up on my bars we were all talking about this. We talked about starting a magazine where all the contributors have the bars. When we started doing some research we found people from all over the world with this tattoo, which is ironic because Black Flag as a band never really extensively toured outside of the US. They are an American band, even more so a regional band from the west coast.

For people all over the world to have this tattoo there had to be more to it. It’s not like they are Led Zeppelin, there’s not a huge fandom for Black Flag. During my research, I asked people what motivated them to get the bars tattoo. It was always something different, like, ‘It connects me to the punk community from which I came, I feel like its dying now’ or ‘I feel like I am getting older and it is the best way for me to stay connected,’ or ‘It’s a great way to meet other people because if that person has the same tattoo you know they came from the same background.’ So I put out the word and set up a tour of the U.S., Canada and Europe to meet and interview all these people and photograph them.

Because the band, for the most part, declined to participate, everything had to be told through the fans, the people that we interviewed and photographed, and then I just sort of laid a narrative under it about participating in the scene, why someone would want to be a punk rocker in the 80’s despite being constantly tormented, fucked with and threatened with grievous bodily harm and what not. What would make a person do that? One unexpected twist was that the average age of people contributing  to the book was 25, and when we did the tour Black Flag had been broken up for 26 years, so the vast majority of people in our book were not even alive when Black Flag was active. I think that is a testament to the enduring power of the music and the scene that Black Flag created.

to the book was 25, and when we did the tour Black Flag had been broken up for 26 years, so the vast majority of people in our book were not even alive when Black Flag was active. I think that is a testament to the enduring power of the music and the scene that Black Flag created.

PHAWKER: Why do you think their music continued to speak to succeeding generations of angry young people?

STEWART EBERSOLE: In the ’80s there were punk bands like the Dead Kennedys singing about Ed Meese, Ronald Reagan and the wars in Nicargua El Salvador, they basically put a time stamp on their music. Their music is about 1981. People are looking for something more emotional than they are something political in music. Black Flag was singing about the poltics of people’s emotions, so their music doesn’t have a time stamp. Ninety percent of the audience for punk rock in 1981 and 1982 was fucked up kids. I was kind of a mess and I know most of my friends were a mess but we were trying to make a go of it and if you didn’t fit into the normal world, punk rock was great because you didn’t have to. Black Flag was a band singing about about not wanting to go back to the normal world, not wanting to deal with the authority figures, not wanting to climb with the social ladder. Those songs spoke to pissed off kids. And they still do.