SLICING UP EYEBBALLS: A newly revealed cassette recording of The Smiths rehearsing in a Manchester warehouse in May 1983 — prior to signing their first record deal — has surfaced online, collecting performances of nine songs with early arrangements and lyrics in what the band’s drummer today called “an early recording you’ve probably never heard before.” Dubbed “The Pablo Cuckoo Tape” after the pseudonym given the “source close to the band who made the recording,” the 40-minute performance initially was shared via smithstorrents.co.uk and now has been uploaded to YouTube, and can be streamed via the player embedded below. The sound of the cassette, apparently recorded to give to early producer Troy Tate, is, not surprisingly, somewhat rough. But it does find Morrissey and Co. running through early versions of tracks that would end up on their 1984 debut, including future classics “What Difference Does It Make?” and “Hand in Glove.” MORE

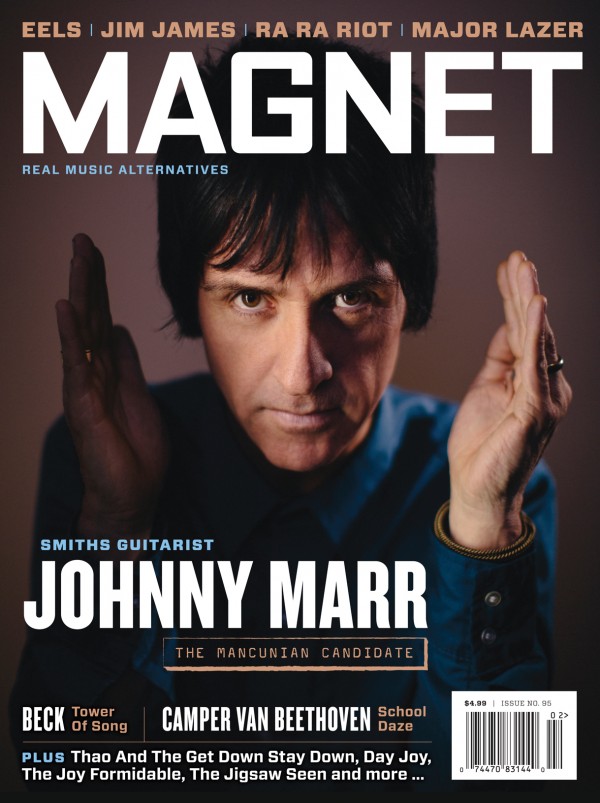

EXCERPT: The Importance Of Being Johnny Marr

BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR MAGNET MAGAZINE Being Johnny Marr is nice work if you can get it. Lots of travel, flexible hours, money for nothing, chicks for free. Most days you walk between the raindrops. You are rakishly handsome, impossibly talented, effortlessly cool and beloved by all. Born in Manchester and raised in public housing, you meet your soulmate when you were 14, you quit school when you were 15, and at the ripe old age of 18 you start a band that NME readers will, 20 years hence, declare the most important band of the last 50 years, edging out the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Small wonder everyone wants you to join their band in the studio or onstage for a song or a tour, or even an album or two: the Talking Heads, the Pretenders, Modest Mouse, R.E.M., Beck, Oasis, Bryan Ferry, Pet Shop Boys, Billy Bragg, Black Grape, Jane Birkin, Happy Mondays, The The, Chic, Dinosaur Jr, Pearl Jam, Crowded House, Tom Jones and, last but not least, the guy who started Joy Division. You almost never say no, because you are not just a legend, you are also a nice guy.

Here you are, a year shy of 50. You still have the soulmate, two grown children, your looks and all your hair, plus a line of Fender Jaguars named after you, along with a numbered limited edition of Johnny Marr Ray-Ban Signet sunglasses with light blue-tinted lenses and gunmetal frame. And, best of all, 25 years after walking away from your own band, you are finally going solo. “The ideas became stronger to me and the well filled up—that’s the right time to do it,” Marr says when asked what took so long. “It was pretty much all there before I started to work with it.” The album is called The Messenger and it is easily your best work since the Smiths, some of it is clearly as good as the Smiths and some of it, arguably, is better than the Smiths.

Ah yes, the Smiths. Before we go any further, let’s just get this out of the way: The Smiths will not be reuniting. Not now, not ever. Not that I didn’t try to make it happen, but the sad reality is when the queen is dead, she stays dead. A full Beatles reunion is more likely. Or, to quote Morrissey’s publicist, “The Smiths are never, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever going to reunite—ever.” And if the more determined among you can parse that quote for a glimmer of hope that there’s still an outside chance of a reunion, please note that there’s eight “ever”s in that statement, meaning eight eternities in a row that will have to run their course before a Smiths reunion comes to pass. Given that the median age of the members of the Smiths is 50, and the life expectancy for British males is currently 78.2 years, it doesn’t look good. MORE

RELATED: JOHNNY MARR PLAYS THE TROCADERO TUESDAY APRIL 3TH

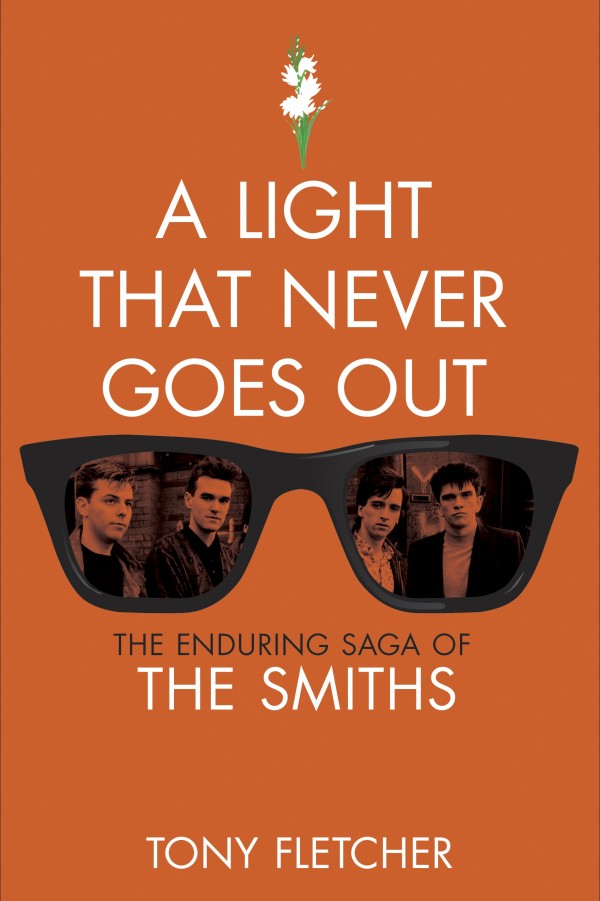

WORTH REPEATING: How Soon Is Now?

It takes a particular confidence for one unknown musician to pronounce to another that their first meeting has the hallmarks of legend. But then Johnny Marr, eighteen years old when he arrived uninvited at the Stretford home of Steven Patrick Morrissey one afternoon in May of 1982, had such confidence in abundance; what he did not have, and it was the reason he had come knocking on the door of the nondescript semidetached council house at 384 Kings Road that day, was a partner for his singular talent on the guitar.

Steven Morrissey, a writer of speculative merit and a singer of absolutely no repute whatsoever, managed but sporadic bursts of self-assurance. Though he had been a figure about town since punk rock had exploded in Manchester with a special vigor back in 1976, and was respected, even liked, for his quick wit and bookish intellect, he frequently retreated into a shyness that, as he later penned with devastating certitude, was “criminally vulgar.” Unlike Marr, who seemed to be on first-name terms with almost everyone involved in Manchester street culture, Morrissey could count his friends on the fingers of one hand. He lived on Kings Road with his divorced mother. He was unemployed—by choice, for sure, but unemployed all the same. He was turning twenty-three that month. By any standard measurement, time appeared to be passing him by.

Aware of Morrissey’s shyness, Marr did not show up alone. He was accompanied on his mission by Stephen Pomfret, a mutual guitar-playing acquaintance whose presence was perhaps justified by the painfully long time it took Morrissey to descend from his bedroom to the front door. But once Pomfret had made the introductions, then Marr, not known to waste his time on trivialities, announced that he was on a quest for a singer and lyricist, and Morrissey, not previously known to accept strangers into his life at first glance, promptly invited the visitors in. MORE