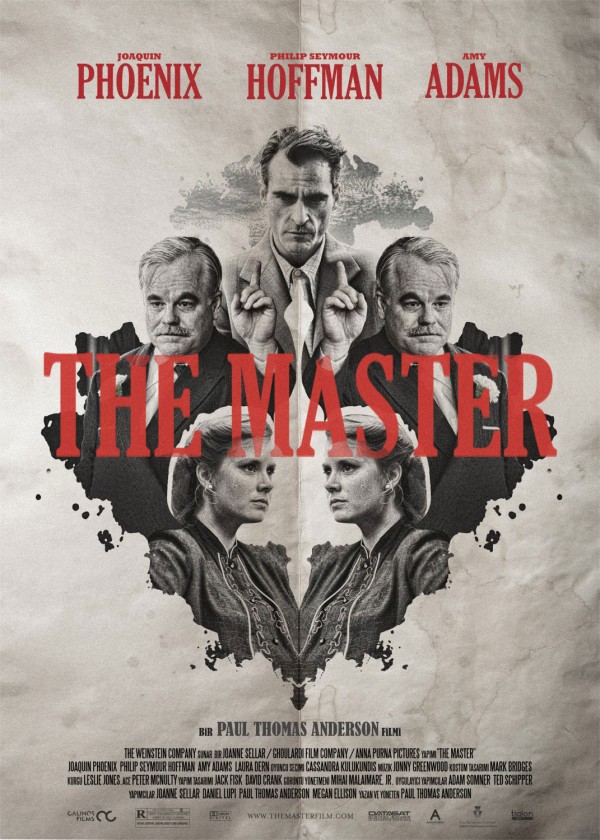

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC It might come as no surprise to see The Master on a Best of 2012 list, but it is a surprise to me, someone who has always found Paul Thomas Anderson films to display a lot of craft masking simplistic or vague ideas. Exploring an odd, symbiotic relationship between religious charlatan and a shell-shocked ex-G.I. addict, Anderson’s latest is the most intimate of epics, a film that attempts to tell the story of the 20th century while most of its scenes take place in small rooms. The Master itself is not overloaded with action and Anderson seems less interested than ever in leading us to pat conclusions. The Master fits that old phrase, “a personal film” in that  everyone who sees it seems to come away with a different idea on what the film is about. For me, it was the most captivating of Anderson’s stories of unparented, stunted individuals struggling for identity amongst their surrogate family.

everyone who sees it seems to come away with a different idea on what the film is about. For me, it was the most captivating of Anderson’s stories of unparented, stunted individuals struggling for identity amongst their surrogate family.

The Master dissembles religion’s controlling power almost as a side-note, but religious domination is front and center in Romanian director Christian Mingiu’s in his latest, Beyond the Hills. A young Moldovian woman comes to stay with her closest friend in an austere Christian sect. Beyond the Hills was summarized in early reviews as Mingui’s “exorcism” picture, but that charged word did not prepare me for the long, rational build-up to the act, a slow unfolding that leads us to believe the situation is less extreme than it really is . The smack of reality at the film’s climax felt like a cold slap in the face.

I was thinking of the contrast in two directors who crashed upon the scene in the 1990s, Richard (Slacker) Linklater and Quentin (no introduction needed) Tarantino.) While Tarantino seems desperate to make each of his films a national trauma, Linklater has quietly doubled his pace as a director and assembled a fascinating body of work that sets him among the most thoughtful of American filmmakers critical of contemporary America. With the whimsical Bernie Linklater’s touch reminded me of the 1970s work of Hal (Harold & Maude) Ashby or Robert (Nashville) Altman, with the same generosity that gives every character who wanders on screen their own minute of business, Based on fact, Bernie (a restrained performance from Jack Black) is a sweet-natured, community-orientated assistant funeral director whose relationship with a surly, wealthy widow (Shirley MacLaine) builds slowly to murder. While you’d expect a Texas small town would find no mercy in their heart for a murderer, Linklater reveals an unexpected empathy for Bernie and his misdeeds.

I was thinking of the contrast in two directors who crashed upon the scene in the 1990s, Richard (Slacker) Linklater and Quentin (no introduction needed) Tarantino.) While Tarantino seems desperate to make each of his films a national trauma, Linklater has quietly doubled his pace as a director and assembled a fascinating body of work that sets him among the most thoughtful of American filmmakers critical of contemporary America. With the whimsical Bernie Linklater’s touch reminded me of the 1970s work of Hal (Harold & Maude) Ashby or Robert (Nashville) Altman, with the same generosity that gives every character who wanders on screen their own minute of business, Based on fact, Bernie (a restrained performance from Jack Black) is a sweet-natured, community-orientated assistant funeral director whose relationship with a surly, wealthy widow (Shirley MacLaine) builds slowly to murder. While you’d expect a Texas small town would find no mercy in their heart for a murderer, Linklater reveals an unexpected empathy for Bernie and his misdeeds.

Matthew McConaughey is a lawman seeking justice and political gain in Bernie, and he keeps his cowboy hat and Southern drawl as the title character in William Friedkin’s adaptation of Tracy Letts’ playKiller Joe. McConaughey is an even more lowdown lawman here, Joe is a police detective with a sideline of contract killing. He’s dragged into a domestic drama of some trailer park-dwelling folk who want him to murder the family matriarch for the insurance money. Friedkin, still unjustifiably raunchy in his mid-70s, gives the viewer sadistic satisfaction in watching bad thing happen to bad people, as these addled dumbells rue the day they let Detective Joe Cooper comes into their lives. Transcendently lurid.

Detropia, a look at the once booming industrial city of Detroit, evokes dystopian fears better than any made-up zombie meltdown. The documentary team of Rachel Grady & Heidi Ewing (Jesus Camp) craft a loving portrait that shows the national cultural hub of Detroit left hung out to dry by the forces of free market capitalism. Sometimes the sorry state of the city is played for sentiment, other times the sights are allowed to speak for themselves, exuding a surreal spell as we see spectacular images of decay. A single image, that of a twenty floor high rise reduced to a towering sliver, just swaying in the breeze, wowed me more than any of those shifting computer-generated cityscapes in Inception a few years back. While the city is still populated with earnest citizens, Detropia shows how this test tube for fiscal “austerity” has turned a once-great city into a weird post-collapse nightmare.

Detropia, a look at the once booming industrial city of Detroit, evokes dystopian fears better than any made-up zombie meltdown. The documentary team of Rachel Grady & Heidi Ewing (Jesus Camp) craft a loving portrait that shows the national cultural hub of Detroit left hung out to dry by the forces of free market capitalism. Sometimes the sorry state of the city is played for sentiment, other times the sights are allowed to speak for themselves, exuding a surreal spell as we see spectacular images of decay. A single image, that of a twenty floor high rise reduced to a towering sliver, just swaying in the breeze, wowed me more than any of those shifting computer-generated cityscapes in Inception a few years back. While the city is still populated with earnest citizens, Detropia shows how this test tube for fiscal “austerity” has turned a once-great city into a weird post-collapse nightmare.

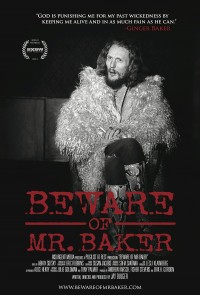

Collapse is all around drum great Ginger Baker too, in one of the rock excess stories to end them all, the expertly told in Beware of Mr. Baker. As someone who  has read the rock press for decades, I was shocked I’d never read any brawling anecdotes about Mr. Baker, who relocated from England to Nigeria, to Italy, the U.S. and finally to South Africa, leaving a trail of wives, broken business, broken noses and general chaos in his wake. While reveling in the bad behavior, the film makes a serious case for Baker as the man to re-imagine rock drumming, a musician who opened the door for rock music to expand its conception of the rhythmic possibilities of the form. Director Jay Bulgar gets some intriguing personal time with Baker in his South African bunker, capturing shades of vulnerability and fear as his years as a drummer seems to be escaping. Brilliant profile of a brilliant musician with a genius for beauty and destruction.

has read the rock press for decades, I was shocked I’d never read any brawling anecdotes about Mr. Baker, who relocated from England to Nigeria, to Italy, the U.S. and finally to South Africa, leaving a trail of wives, broken business, broken noses and general chaos in his wake. While reveling in the bad behavior, the film makes a serious case for Baker as the man to re-imagine rock drumming, a musician who opened the door for rock music to expand its conception of the rhythmic possibilities of the form. Director Jay Bulgar gets some intriguing personal time with Baker in his South African bunker, capturing shades of vulnerability and fear as his years as a drummer seems to be escaping. Brilliant profile of a brilliant musician with a genius for beauty and destruction.

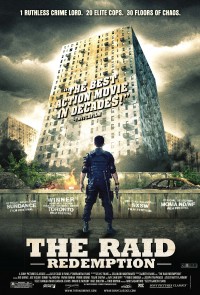

As much as I love cinema that leads me to obscure philosophical musings in exotic corners of the world, I’m always game for ingeniously visceral roller coaster rides. This used to be the purview of Hollywood but so many of the blockbusters that seem meant to provide those thrills get too caught up in franchise demands or overblown computer effect to really take the breath away. Again this year, it seems as if Asia is where you went to experience the most heady action film thrills. The Raid: Redemption demonstrates that a simple premise doesn’t have to be simple-minded. A SWAT team arrives at a 30 Floor tenement to arrest the drug kingpin on the top floor, only to find that their surprise raid was no secret, and the tenement is booby-trapped at their arrival. The Raid builds like a great piece of music, adding and subtracting elements and dancing wildly from one space to the next. Much of its thrills are built around real stunts, unaided by post-production trickery, the type of craft I can never get enough of. Although made in Indonesia with a local cast and crew, The Raid was directed by Welsh-born Gareth Evans.

As much as I love cinema that leads me to obscure philosophical musings in exotic corners of the world, I’m always game for ingeniously visceral roller coaster rides. This used to be the purview of Hollywood but so many of the blockbusters that seem meant to provide those thrills get too caught up in franchise demands or overblown computer effect to really take the breath away. Again this year, it seems as if Asia is where you went to experience the most heady action film thrills. The Raid: Redemption demonstrates that a simple premise doesn’t have to be simple-minded. A SWAT team arrives at a 30 Floor tenement to arrest the drug kingpin on the top floor, only to find that their surprise raid was no secret, and the tenement is booby-trapped at their arrival. The Raid builds like a great piece of music, adding and subtracting elements and dancing wildly from one space to the next. Much of its thrills are built around real stunts, unaided by post-production trickery, the type of craft I can never get enough of. Although made in Indonesia with a local cast and crew, The Raid was directed by Welsh-born Gareth Evans.

This year I was never more charmed by beauty, suspense, and romance as I was watching The Thieves, an elegant heist film worthy of comparison to classics  like Riffifi or The Hot Rock. Dazzling like the best of Bond, a group of Hong Kong thieves (including longtime action star Simon Yam) meet up with a Korean gang to rob a casino in glimmering Macao. Again, it is an amazing display of craft that director Choi Dong-Hoon exhibits, juggling inter and extra-group rivalries, Spring and Autumnal romances and traitors in their midst, with a cast that embodies that sort of old Hollywood mystique. The woman in the plot are more than mere eye-candy as well, instead being fully-drawn characters with drives and schemes all their own. Sometimes you’ll watch a caper and hold your breath, hoping that the director can keep all the balls in the air. From the onset The Thieves shows an elegance and mastery that puts you at ease and lets you know you’re in confident hands. And what a finale!

like Riffifi or The Hot Rock. Dazzling like the best of Bond, a group of Hong Kong thieves (including longtime action star Simon Yam) meet up with a Korean gang to rob a casino in glimmering Macao. Again, it is an amazing display of craft that director Choi Dong-Hoon exhibits, juggling inter and extra-group rivalries, Spring and Autumnal romances and traitors in their midst, with a cast that embodies that sort of old Hollywood mystique. The woman in the plot are more than mere eye-candy as well, instead being fully-drawn characters with drives and schemes all their own. Sometimes you’ll watch a caper and hold your breath, hoping that the director can keep all the balls in the air. From the onset The Thieves shows an elegance and mastery that puts you at ease and lets you know you’re in confident hands. And what a finale!

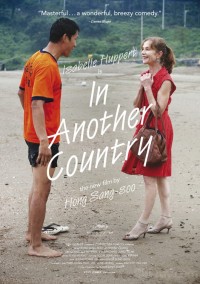

Often I find myself criticizing the lack of believable “reality” a film is able to summon in its attempt to convince me that a film star is whatever role they’re selling, whether it is a tough cop, a scientific genius or a master criminal. So what happens when a film dispenses with that illusion entirely? In the always clever Hong Sang-soo’s latest In Another Country, he tells three stories, all involving a French woman arriving for a stay in a little room in a quiet seaside town. Of course, since that woman is played in each section by Isabelle Huppert, the actress quickly establishes herself as a different persona, alternately strong, needy and reflective. Although the character changes the place does not, and it I wonderful to watch how differently Huppert’s women react to the same stimulation surrounding them.

Often I find myself criticizing the lack of believable “reality” a film is able to summon in its attempt to convince me that a film star is whatever role they’re selling, whether it is a tough cop, a scientific genius or a master criminal. So what happens when a film dispenses with that illusion entirely? In the always clever Hong Sang-soo’s latest In Another Country, he tells three stories, all involving a French woman arriving for a stay in a little room in a quiet seaside town. Of course, since that woman is played in each section by Isabelle Huppert, the actress quickly establishes herself as a different persona, alternately strong, needy and reflective. Although the character changes the place does not, and it I wonderful to watch how differently Huppert’s women react to the same stimulation surrounding them.

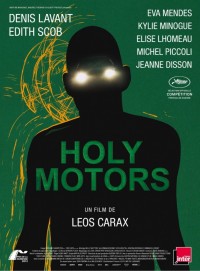

I fell hook, line, and sinker for the similarly-themed Holy Motors, in which the mesmerizing actor/contortionist/acrobat Denis Lavant rides around in a  limousine, on a job that calls for him to change characters continuously. Again, although it has been shown that Lavant’s Mr. Oscar is just an actor playing a role, I found myself shocked when he turned into a lascivious leprechaun, offended when he transformed into the badgering father of a schoolgirl and hypnotized when he donned a suit of light and danced. Director French Leo Carax’s first trio of films (major personal favorites) – Boys Meets Girl, Bad Blood, and Lovers on a Bridge in their English titles – were delirious paeans to romantic love, a subject it seemed that he had explored to its deepest, most primal root. With Holy Motors he returns to that overwhelming emotion yet his subject matter appears to be the love of cinema itself The entire film is a testament to why perfectly reasinable people spend hours in the dark, staring; to bring beauty and context to their lives. Just remembering the film makes me anxious to watch more in 2013.

limousine, on a job that calls for him to change characters continuously. Again, although it has been shown that Lavant’s Mr. Oscar is just an actor playing a role, I found myself shocked when he turned into a lascivious leprechaun, offended when he transformed into the badgering father of a schoolgirl and hypnotized when he donned a suit of light and danced. Director French Leo Carax’s first trio of films (major personal favorites) – Boys Meets Girl, Bad Blood, and Lovers on a Bridge in their English titles – were delirious paeans to romantic love, a subject it seemed that he had explored to its deepest, most primal root. With Holy Motors he returns to that overwhelming emotion yet his subject matter appears to be the love of cinema itself The entire film is a testament to why perfectly reasinable people spend hours in the dark, staring; to bring beauty and context to their lives. Just remembering the film makes me anxious to watch more in 2013.