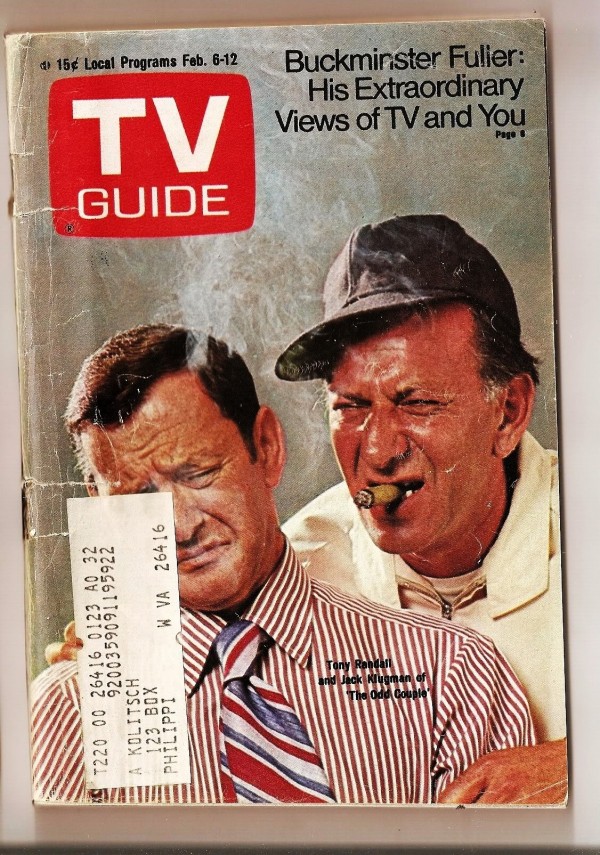

NEW YORK TIMES: His features were large and mobile; his voice was a deep, earnest, rough-hewed bleat. He was a no-baloney actor who conveyed straightforward, simply defined emotion, whether it was anger, heartbreak, lust or sympathy. That forthrightness, in both comedy and drama, was the source of his power and his popularity. Never remote, never haughty, he was a regular guy, an audience-pleaser who proved well-suited for series television. Mr. Klugman was already a decorated actor in 1970 when he began co-starring in “The Odd Couple,” a sitcom adaptation of Neil Simon’s hit play about two divorced men — friends with antagonistic temperaments — sharing a New York apartment. (A film version was released in 1968 with Walter Matthau reprising his Broadway performance as Oscar.) Opposite Mr. Klugman’s Oscar, an outgoing slob with a fondness for poker, cigars and sexy women, was Tony Randall as the pretentious fussbudget Felix Unger (spelled Ungar in the play and the film). He also had more than 100 television credits behind him, including four episodes of “The Twilight Zone” and a 1964 episode of the legal drama “The Defenders,” in which he delivered an Emmy Award-winning performance as a blacklisted actor. In the movies he had been the nouveau-riche father of a Jewish American princess (Ali MacGraw) in “Goodbye, Columbus” (1969); a police colleague of Frank Sinatra’s in “The Detective” (1968); Jack Lemmon’s Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor in “Days of Wine and Roses” (1962); and a murder-trial juror, alongside Henry Fonda, in “12 Angry Men” (1957). In his solo moment in that film, his character, known only as Juror No. 5, recalls growing up in a tough neighborhood and instructs his fellow jurors in the proper use of a switchblade, a key element in their deliberations. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: He was born in Philadelphia on April 27, 1922, the youngest of six children of immigrants from Russia. Most sources indicate that his name at birth was Jacob, though Mr. Klugman said in an interview that the name on his birth certificate is Jack. His father, Max, was a house painter who died when Jack was 12. His mother, Rose, was a milliner who worked out of the family home in hardscrabble South Philadelphia, where Jack grew up shooting pool, rolling dice and playing the horses. His interest in acting was kindled at 14 or 15 when his sister took him to a play, “One Third of a Nation,” a “living newspaper” production of the Federal Theater Project about life in an American slum; the play made the case for government housing projects. “I just couldn’t believe the power of it,” he said of the production in an interview in 1998 for the Archive of American Television, crediting the experience for instilling in him his social-crusading impulse. “I wanted to be a muckraker.” After a stint in the Army — he was discharged because of a kidney ailment — Mr. Klugman returned to Philadelphia but racked up a debt to loan sharks who were so dangerous that he left town. He landed in Pittsburgh, where he auditioned for the drama department at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University). “They said: ‘You’re not suited to be an actor. You’re more suited to be a truck driver,’ ” he recalled. But this was 1945, the war was just ending and there was a dearth of male students, so he was accepted. “There were no men,” he said. “Otherwise they wouldn’t have taken me in.” MORE

WASHINGTON POST: Few people remember it today, but he also played an instrumental role in passing critical health-care legislation, the Orphan Drug Act, through Congress in the early 1980s, using “Quincy” and his own celebrity to roll Sen. Orrin Hatch (R), who was blocking the bill. Klugman’s unlikely star turn in Washington stemmed from a 1980 hearing by the House Subcommittee on Health and the Environment on the problem of developing treatments for rare diseases. The problem was that many terrible diseases didn’t afflict enough people to entice pharmaceutical companies to develop treatments. Hence they were ”orphan” diseases. They included Tourette’s syndrome, muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, spina bifida, ALS and many more. The situation was especially tragic because scientists who discovered promising treatments often couldn’t interest drug makers, who didn’t see potential for profit. MORE

WASHINGTON POST: Few people remember it today, but he also played an instrumental role in passing critical health-care legislation, the Orphan Drug Act, through Congress in the early 1980s, using “Quincy” and his own celebrity to roll Sen. Orrin Hatch (R), who was blocking the bill. Klugman’s unlikely star turn in Washington stemmed from a 1980 hearing by the House Subcommittee on Health and the Environment on the problem of developing treatments for rare diseases. The problem was that many terrible diseases didn’t afflict enough people to entice pharmaceutical companies to develop treatments. Hence they were ”orphan” diseases. They included Tourette’s syndrome, muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, spina bifida, ALS and many more. The situation was especially tragic because scientists who discovered promising treatments often couldn’t interest drug makers, who didn’t see potential for profit. MORE

RELATED: Charles Durning, who overcame poverty, battlefield trauma and nagging self-doubt to become an acclaimed character actor, whether on stage as Big Daddy in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” or in film as the lonely widower smitten with a cross-dressing Dustin Hoffman in “Tootsie,” died on Monday at his home in Manhattan. He was 89. Charles Durning may not have been a household name, but with his pugnacious features and imposing bulk he was a familiar presence in American movies, television and theater, even if often overshadowed by the headliners. If his ordinary-guy looks deprived him of leading-man roles, they did not leave him typecast. He could play gruff and combative or gentle and funny. His Big Daddy, the bullying, dying plantation owner in a 1990 Broadway revival of Tennessee Williams’s “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” brought him a Tony Award for best featured actor in a play. Frank Rich, then the chief drama critic for The New York Times, likened the performance to “a dying volcano, in final, sputtering eruption.” MORE