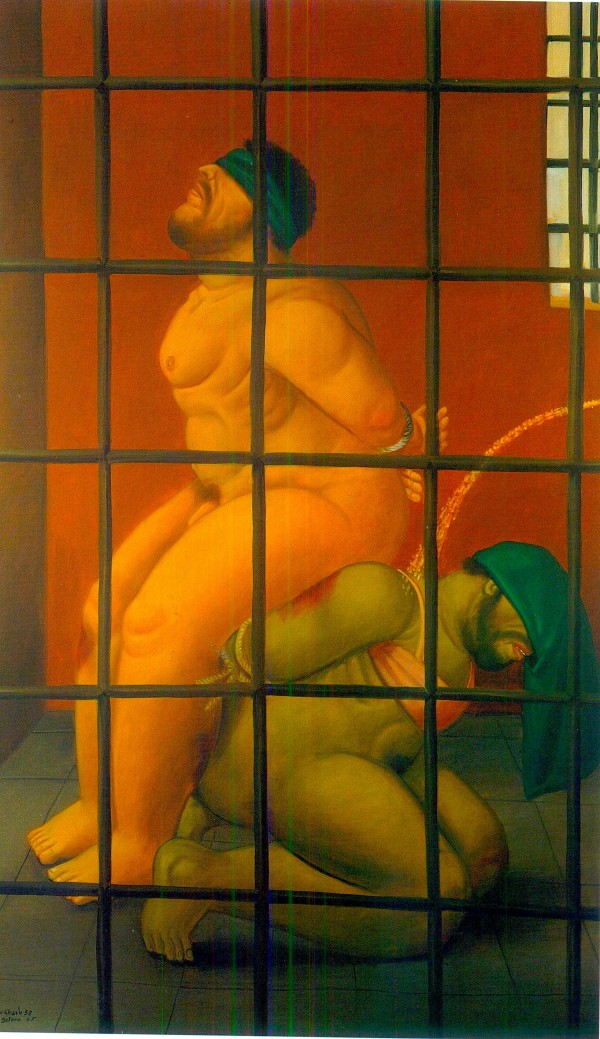

Painting by Fernando Botero

BY JEFF DEENEY Recently I had a rare opportunity to go inside Philadelphia’s House of Corrections, the oldest jail in the Philadelphia Prison System, and see the conditions inmates live in. I was there in my capacity as a social worker and not as a writer and frankly I had no intention of writing about the experience. But as I walked the block prisoners implored me to, perhaps thinking I was a reporter, so I feel I must report on their behalf.

BY JEFF DEENEY Recently I had a rare opportunity to go inside Philadelphia’s House of Corrections, the oldest jail in the Philadelphia Prison System, and see the conditions inmates live in. I was there in my capacity as a social worker and not as a writer and frankly I had no intention of writing about the experience. But as I walked the block prisoners implored me to, perhaps thinking I was a reporter, so I feel I must report on their behalf.

“Tell them out there about this overcrowding you seen here!”

“Put it in the papers!”

These shouts echoed through the halls as I was quickly shuffled through by prison staff. The conditions prisoners live in was incredibly disturbing to me, and I say this as someone who has been on every locked psych ward in this city. I’ve seen some soul-withering human degradation; this was orders of magnitude worse.

House of Corrections (HoC) was built to comfortably house about 900-1000 prisoners and has a maximum capacity of roughly 1200. On the day I was there, the head count was 1650. Of these 1650 only 150 have been convicted of crimes. The rest are only charged with crimes, presumed innocent and pending hearings before a judge. Cramming this many prisoners in such a small space creates conditions that are incredibly unsafe and unsanitary. Three prisoners are held in tiny cells built to hold two. Three men packed in a space the size of a walk-in closet also use a toilet and sink in the same space. With so many people creating unsafe conditions the facility is on “lock down” almost daily which means prisoners also eat in the same space they use the bathroom in and have no time out for physical activity. The place stunk and most prisoners laid listlessly in their narrow cots, thin blankets pulled over their heads. Inmates told me it was worse over the summer; HoC has no air conditioning and apparently there were extensive water outages so bathing and laundry didn’t happen much.

It’s not just HoC that is this overcrowded. Each of the five jails located on the State Road prison complex in northeast Philly is this overcrowded. The women’s prison is this overcrowded. The population of the entire system is approaching a record 9,000 inmates. Holmesburg Prison, the ancient facility that was long ago decommissioned, is open for business again despite that fact that it’s not fit for human habitation. The overcrowding is causing an overflow of psychiatric emergency calls that are drowning the system’s understaffed mental health unit. Not surprisingly, there has been a rash of suicides. There have also been murders. Scant details about it all make the newspapers, as the flow of information into and out of the system is so tightly controlled.

Many prisoners in HoC say the conditions in the state system are better and request to go to Graterford. Imagine that, requesting to do time with lifers. With all the recent coverage about the negative impacts of solitary confinement you’d think there would be no way any prisoner would ever want to be held in seclusion but inmates here will intentionally do things to be put in the hole in order to get a brief respite of quiet, safety and privacy. House of Corrections is so old that scavenging scrap metal for fashioning a “whack,” as shivs are called in Philly, is easy. Corrections officers complain that getting stuck with whacks is all too common when the overcrowding is this bad; inmates complain of “the ninjas,” roving crews of whack wielding stick up artists who wrap bedsheets around their heads to conceal their identities and run up into cells in order to steal an inmate’s commissary.

Prison overcrowding is an endemic national problem but that’s not what’s happening here. Philadelphia’s overcrowding isn’t in line with any national trend; it’s a recent sharp spike in population directly caused by changes made to the way defendants are handled in the courts. These changes made by the courts were a direct response to a fear-inspiring series by Inquirer reporters Craig McCoy, Nancy Philips, and Dylan Purcell entitled, Justice: Delayed, Dismissed, Denied. The piece was heavy on visual and written images of black men with guns and detailed accurately how many violent crime cases fall apart due to witness intimidation facilitated by a glacially-slow moving justice system. The piece underlined the fact that there are tens of thousands of fugitives on the streets on any given day and clearly drew the conclusion that solving the problems of court dysfunction and holding fugitives accountable would help solve the city’s violent crime problem.

The integral role that the drug war plays in all this was conspicuously absent from the paper’s court coverage, which was heavily informed by law enforcement sources. Also MIA was the aggravating factor of gross income inequality. The Inquirer series never seriously considers the incontrovertible fact that the reason the courts are so clogged is because so much nonviolent drug- and poverty-related behavior has been criminalized. The paper says murders can’t be adequately tried because the system is so overloaded but never once recommends flushing out the system through decriminalizing nonviolent behaviors and thereby free up prosecutors to focus their limited resources on actual crimes. In fact, you could have written an entirely different series about the courts at that time that came to a radically different set of conclusions.

It’s not like those alternative solutions weren’t already out there. In 2006 Penn law professor David Rudofsky filed a lawsuit against prison overcrowding that nailed this point. “With the war on drugs, you have an inexhaustible supply of possible prisoners, limited only by the number of police you have,” Rudovsky told ABC News in 2006. His lawsuit described deplorable prison conditions that mirror current conditions, with numbers that were similarly unconscionable.

The courts responded to The Inquirer series, crafting a series of reforms that were covered in favorable terms, allowing the panel that crafted them to call their own efforts in a later story “remarkable” while having them refer back to his own original series, praising it as a “scathing indictment” of their undeniable dysfunction. The paper has basically done a series of victory laps that laud their own coverage and the efforts of court reformers they’re covering.

In fact the panel’s recommendations have improved very little and have created mass human suffering inside the prison system that violates constitutional law forbidding “cruel and unusual” punishment. It’s Our Money wrote about prison conditions recently on Philly.com, sourcing Rudovsky, but the Inquirer itself has yet to follow up with any coverage that connects the current conditions in prison to the series that caused and subsequently reinforced them. The Inquirer needs to own this outcome.

Bench warrant court is one of the prime drivers of current prison overcrowding. The prison population spiked directly after the inauguration of this new initiative. In a hurry to solve the city’s fugitive problem after the Inquirer decided it was the root cause of crime in the city, the courts developed an extremely punitive get-tough policy for those who fail to appear in court in the hopes of improving defendant accountability. Now if you fail to appear in court, even if it’s your first time, you immediately do five days in jail as a sanction for contempt.

Sounds like a slap on the wrist, right? It’s frequently not, because once you’re in the system you can be held on bail after your five day sanction, and if you’re poor and can’t afford to pay, you are stuck inside until a judge in this molasses-paced system finally gets around to you and lets you out. You see, the Inquirer decided that the broken bail system was driving violent crime too, and that irresponsible defendants need to be taught a lesson. An eagerly punitive panel of court experts was quick to oblige, regardless that such new measures would be disproportionately harsh on the poorest defendants, those who can’t get even $500 together to make bail.

The mentally ill, the homeless, the working poor, and the most low level offenders now sit for weeks or even months of pretrial waiting for someone to let them out or hear their case. The perception among defendants is that nobody gets ROR anymore, it seems like everyone has to pay cash. Of course, the real-deal gangsters have cash and are right back on the streets in a matter of hours. The most prosperous street crews that employ the most reckless young hustlers still keep cash bail funds that can be used to get their teammates out of jail. The most likely to be violent criminals still walk while the most vulnerable continue to rot in jail.

Two actual cases in point. A single father with a 12-year-old child who is employed full time has missed court four times. He’s charged with possessing $5 worth of marijuana. He says he misses court so much because he can’t take off work or he’ll lose his job. If he does go to court, he’s afraid that things move so slowly that he won’t be able to pick his kid up from school. So he blows off court, even though he knows it’s not the right thing to do. He honestly doesn’t think much of the bench warrant he has because it’s for a piece of one measly blunt.

When he finally surrenders on his warrant, he’s processed through bench warrant court. He’s sanctioned to five days in jail, but while he’s inside his bail is set at $10,000. He doesn’t have the $1,000, or 10%, he needs to pay to be released. He has no savings, like most Americans these days, he lives paycheck to paycheck. So he sits in jail for nearly six weeks, on a filthy, violent and overcrowded cell block at HoC for having one marijuana blunt. His parents, luckily, are around to watch his child in the meantime. He’s hardly the gun-toting thug the Inquirer whipped up public fear about with their court series, but he’s sitting in jail because of it nonetheless. Worse, he’s incarcerated for a longer period waiting for a hearing than he conceivably would have received as a sentence if he was just found guilty and of such an extremely minor crime. During this time he spends sitting in HoC waiting for a trial he misses his son’s graduation from the 8th grade.

Case number two. A 22-year-old male, also with a petty marijuana charge. He knows he has a warrant for that case, so when he’s stopped and frisked by an officer on the street he gives a false name because he has a baby at home that he cares for during the day while his wife works and he doesn’t want to get locked up for five days with no chance to arrange child care. He admits giving the fake name to the cop was a bad decision, but it’s understandable. When he’s brought in on the warrant he’s also charged with another misdemeanor for false ID to a police officer. These are both summary offenses, by the way, the kind of infraction that would normally result in a citation, not jail time. But, like the other defendant, he winds up spending six weeks in jail held on bail he can’t afford while he waits for a hearing. If his wife paid the bail she couldn’t have paid her rent, because while they’re both employed they both only make minimum wage. Because he is MIA for six weeks, he loses his night job washing dishes in a restaurant. His wife struggles to find child care so she doesn’t also lose her job.

These are the people swelling our jails right now. Many of them will spend more time locked up waiting for hearings than the maximum penalty for their minor “crimes.” So it shouldn’t come as any surprise that the court reforms have yet to make a dent in the city’s violent crime statistics. Maybe that’s because the Inquirer overstated the fugitive problem’s relation to violent crime, or maybe the court’s actions actually have far less impact on crime rates than the series presumed, or maybe any decrease in violent crime the court’s reforms have created are offset by nonviolent criminals becoming more violent to adapt to life in Philly’s hellish prison system who are then returned to their communities with a whole new skill set.

Regardless, while there are serious issues about witness safety and victim’s rights that were highlighted in the Inquirer’s coverage that the courts are doing good work to improve, locking up minor offenders and holding them on bail they can’t afford, stuffing the jails to bursting and saying you’re solving a fugitive problem that drives violent crime is creating more problems than it solves. There are better ideas for easing the burden on our courts such as reevaluating the expansion of criminalized behavior, particularly those associated with drug use and petty distribution by nonviolent poor people. It would be nice to see the newspapers start driving the conversation in this direction while taking ownership of a massive problem they helped create. Maybe the Inquirer could do a solid for the dudes at HoC living in overcrowded and inhumane conditions and do like they asked: put it in the papers.

Jeff Deeney is a social worker and freelance writer who covers poverty, addiction and criminal justice. He is a contributing writer for the Daily Beast and a columnist for TheFix.com.