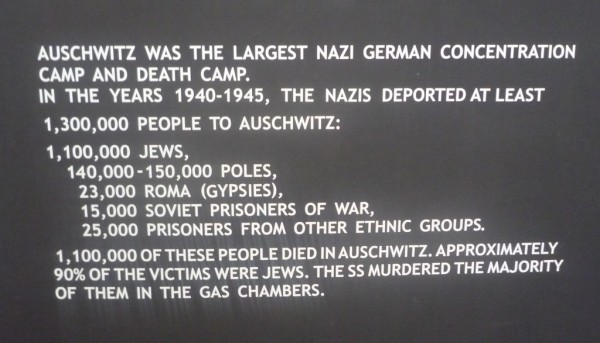

ASSOCIATED PRESS: Germany has launched a war-crimes investigation of an 87-year-old Northeast Philadelphia man it accuses of serving as an SS guard at the Auschwitz death camp, the Associated Press has learned, following years of failed U.S. Justice Department efforts to have the man stripped of his American citizenship and deported. Johann “Hans” Breyer, a retired toolmaker, admits he was a guard at Auschwitz during World War II, but told the AP he was stationed outside the facility and had nothing to do with the wholesale slaughter of about 1.5 million Jews and others behind the gates. The special German office that investigates Nazi war crimes has recommended that prosecutors charge Breyer with accessory to murder and extradite him to Germany for trial on suspicion of involvement in the killings of at least 344,000 Jews at the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp in occupied Poland. Authorities in the Bavarian town of Weiden, who have jurisdiction, are currently trying to determine if the evidence is sufficient for prosecution. A German official working on the case confirmed that Breyer was the target of the probe; he spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to release the information. Breyer acknowledged in an  interview in his modest row house in northeastern Philadelphia that he was in the Waffen SS at Auschwitz but that he never served at the part of the camp responsible for the extermination of Jews. “I didn’t kill anybody, I didn’t rape anybody — and I don’t even have a traffic ticket here,” he told the AP. “I didn’t do anything wrong.” He said he was aware of what was going on inside the death camp, but did not witness it himself. “We could only see the outside, the gates,” he said. MORE

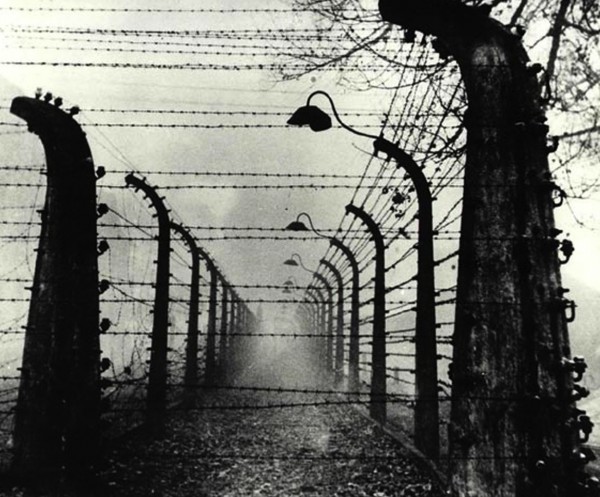

interview in his modest row house in northeastern Philadelphia that he was in the Waffen SS at Auschwitz but that he never served at the part of the camp responsible for the extermination of Jews. “I didn’t kill anybody, I didn’t rape anybody — and I don’t even have a traffic ticket here,” he told the AP. “I didn’t do anything wrong.” He said he was aware of what was going on inside the death camp, but did not witness it himself. “We could only see the outside, the gates,” he said. MORE

2003 FEDERAL CIRCUIT COURT OPINION: Upon completion of a six-week training program, seventeen-year-old Breyer swore an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler. Upon induction into the Waffen SS, Breyer was advised to abandon religion — a policy financially encouraged by waiver of the Reich’s church tax — but he refused. Breyer also refused to join the new inductees in having his blood-type branded on his upper arm, a mark that would have permanently identified him as a member of the Waffen SS. When Breyer was asked in front of a group of new SS inductees whether he could shoot a person, he responded that he could not. Consequently, he was assigned to a section of the concentration camp where prisoner escape was considered unlikely. He carried a weapon while on perimeter duty, but it was not always loaded.

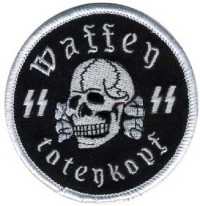

In or around December 1943, Breyer was granted a standard two-week home leave. He was told that if he did not return, his family would be gravely harmed. Breyer took his leave and returned as scheduled. In the spring of 1944, Breyer requested an emergency home leave after receiving word that his mother was ill. This request was denied, but Breyer wrote to inform his parents that he would come home “one way or another.” The letter was intercepted by censors and interpreted as a threat of desertion. As punishment for that perceived threat, Breyer was transferred to another unit of the Totenkopf Sturmbann stationed at Auschwitz I, a slave labor camp in Poland. While there, Breyer maintained essentially the same responsibilities he held at Buchenwald. Breyer testified, and the District Court found, that he never harmed a prisoner at Buchenwald or Auschwitz. Id. at *9. He was aware, however, of the large-scale murder being committed at Auschwitz II, the nearby Nazi death camp.

During his time at the concentration camp, Breyer never attempted to transfer to another type of service or to a different unit. He did, however, request leave every week during his posting at Auschwitz. In April 1944, Franz Karmasin, head of the DP and Slovak State Secretary for Ethnic German Affairs, appealed to the Waffen SS for Breyer’s permanent release from service, urging that Breyer was needed to tend to the family farm on account of his parents’ illness. That appeal was denied, but Breyer was eventually granted temporary home leave in August 1944.

Upon expiration of his scheduled leave, Breyer did not return to Auschwitz — an act of desertion. Although he never stayed at home, Breyer remained in the vicinity, hiding in nearby barns and in the surrounding woods, until at least December 1944 when Slovak Volksdeutschen in Nova Lesna began to evacuate ahead of the advancing Soviet army. Breyer fled the town and attempted to rejoin his unit at Auschwitz. The District Court found that Breyer had done so because he feared being discovered by the Germans and shot as a deserter. Id. at *11. En route, he was informed that the Soviets already had reached the camps at Auschwitz and that his unit was engaged in combat with the Soviet army on the eastern front. Breyer subsequently rejoined his unit near Berlin as a forward observer. Breyer was wounded in March, 1945, but returned to combat three weeks later. On May 3, 1945, his unit surrendered to the Soviet army, whereupon he was shipped to a prisoner-of-war camp in the Czech Republic. Following his release, Breyer reunited with his family in Bavaria. MORE

ASSOCIATED PRESS: A U.S. Army intelligence file on Breyer, obtained by the AP, calls that statement into question. In 1951, American military authorities in Germany carried out a background check on Breyer when he first applied for a visa to the U.S.  The file from that investigation lists him as being with a SS Totenkopf, or “Death’s Head,” battalion in Auschwitz as late as Dec. 29, 1944 — four months after he said he deserted. The Army Investigative Records Repository file was obtained by the AP from the National Archives through a Freedom of Information Act request. The document is significant because judges in 2003 said Breyer’s testimony on desertion was part of what convinced them that his service with the Waffen SS after turning 18 might not have been voluntary, further mitigating his wartime responsibility. Also weighing in Breyer’s favor with the judges was his testimony that he refused to have the SS tattoo; he does not have such a mark today or evidence that one was removed. MORE

The file from that investigation lists him as being with a SS Totenkopf, or “Death’s Head,” battalion in Auschwitz as late as Dec. 29, 1944 — four months after he said he deserted. The Army Investigative Records Repository file was obtained by the AP from the National Archives through a Freedom of Information Act request. The document is significant because judges in 2003 said Breyer’s testimony on desertion was part of what convinced them that his service with the Waffen SS after turning 18 might not have been voluntary, further mitigating his wartime responsibility. Also weighing in Breyer’s favor with the judges was his testimony that he refused to have the SS tattoo; he does not have such a mark today or evidence that one was removed. MORE

RELATED: Breyer lived in Germany until 1952, when he applied for a United States visa under the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, Pub.L. No. 80-774, 62 Stat. 1009, as amended by Pub.L. No. 81-555, 64 Stat. 219 (1950). In his visa application, Breyer acknowledged his membership in the Waffen SS, but did not disclose his participation in the Totenkopf Sturmbann. After initially rejecting his application, the Displaced Persons Commission certified Breyer eligible for a visa in March, 1952. He immigrated to the United States the same year. He later filed a petition for naturalization and was naturalized as a United States citizen in November, 1957. MORE