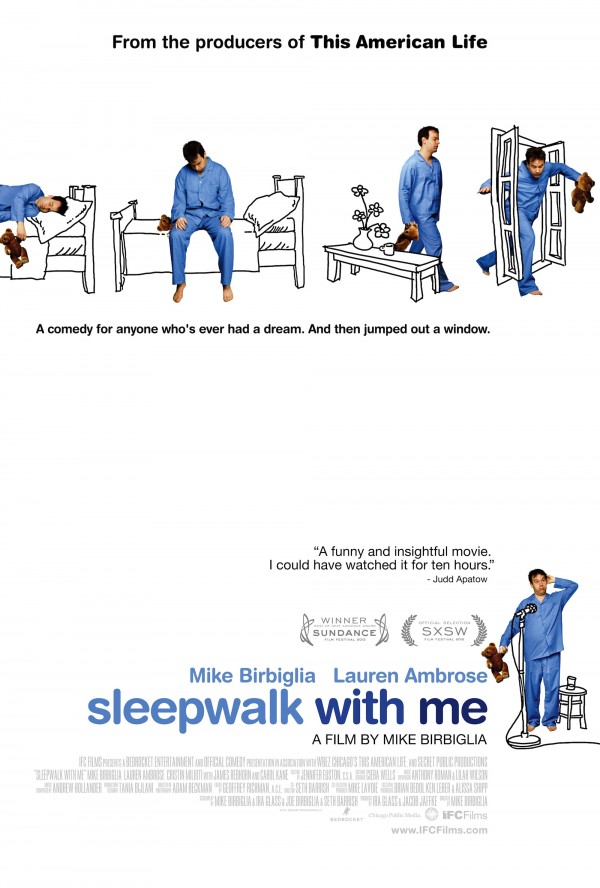

SLEEPWALK WITH ME (2012, directed by Mike Birbiglia and Seth Barrish, 90 minutes, U.S.)

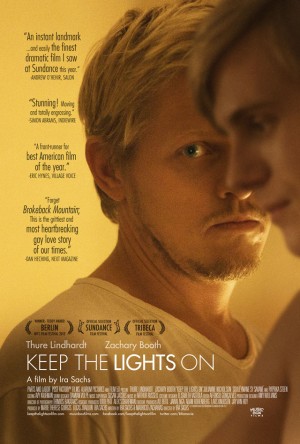

KEEP THE LIGHTS ON (2012, directed by Ira Sachs, 101 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Some of the most-captivating storytelling of the last decade from any medium has come from PRI’s This American Life, the public radio show hosted by Ira Glass. Although the first-person narrative stories the show produces can span the globe, it is a whimsical take on “everyday Americans” that dominates. Sleepwalk With Me is the first film produced directly by This American Life (Ira Glass contributed to the screenplay) and it captures some of the humanistic warmth of the show, while still underlining the yawning chasm between the mediums of film and radio.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Some of the most-captivating storytelling of the last decade from any medium has come from PRI’s This American Life, the public radio show hosted by Ira Glass. Although the first-person narrative stories the show produces can span the globe, it is a whimsical take on “everyday Americans” that dominates. Sleepwalk With Me is the first film produced directly by This American Life (Ira Glass contributed to the screenplay) and it captures some of the humanistic warmth of the show, while still underlining the yawning chasm between the mediums of film and radio.

Front and center is comedian/writer Mike Birbiglia, who has crafted this autobiographical material into a book, a comedy album, and a one-man show, as well as a much-loved segment on This American Life. In transferring this material to the movies, Birbiglia has turned to another nebbish-y star, Woody Allen for inspiration. Addressing the camera, a la Annie Hall, Birbiglia narrates from the driver’s seat of a moving car, presumably on his way to another one-night stand. He’s changed the name of his character to “Matt Pandamiglio” telling the autobiographical story of how his fear of marriage led to bouts of dangerous sleepwalking. Set in the world of stand-up comedians, Mike, er, “Matt” works out his issues, reporting on his progress from the stage to increasingly-amused audiences

Birbiglia is funny in the way your best friend is funny, he may summon a grin but you never think he’s a comic genius. Jerry Seinfeld was in a similar position when he started his sitcom in the early 90s, so he framed his slight, observational humor with some incredibly gifted comic actors, being more than willing to take the role of the straight man responding to their hi-jinks. Birbiglia lacks that generosity; if anyone is going to get a laugh in this film it is going to be himself. Six Feet Under‘s Lauren Ambrose plays his long-suffering girlfriend Abby and it is sad and maybe telling that he can’t make her into anything more than the nag who’s trying to drag him to the alter. All great heroes need great villains and all engaging love stories need a lover the audience loves too. Woody Allen gave the name of his film to his amour in Annie Hall and Diane Keaton found every lovable angle of the character in a way that gives the comedy a real emotional heft. Certainly Ms. Ambrose could uncover layers upon layers of lovability in Birbiglia but he never surrenders the stage long enough for that to happen, a stinginess that ultimately only hurts himself.

Assorted comedians make fleeting appearances (including comic guru Marc Maron as a wise comic sage of the road) but they’re all there merely as characters for Birbiglia to bounce off of, they have no lives of their own. In radio, these first-person narratives can deliver a striking intimacy, but cinematic storytelling demands a wider palette to bring the world to life, and Birbiglia’s blinkered focus begins to secrete the faint odor of an unattractive self-absorption. While the plot itself lacks momentum, Birbiglia’s receding, quietly grumpy character is not much of a spark plug either. Matt is too much of an inert figure, unable to commit to marriage, unsure of how to push ahead in comedy, and unwilling to address his sleepwalking problem.

The film’s dream sequences seem like a perfect place to open up the film and push beyond verbal jokes, yet even the dreams are surprisingly visually tepid, looking like spoofs of bad genre films. When Sleepwalk With Me builds to Matt jumping from a second story window, it feels more like a throwaway scene from a Will Ferrell film than a climactic gag. The more the film resembles a mainstream comedy, the worse it becomes. Sleepwalk With Me’s best moments have nothing to do with the sleepwalking premise or romance, it is the backstage world of stand-up that is the film’s freshest element. There is an inherent drama in the comedian’s struggle to get stage time and the things that happens once he does, but the film short-changes these moments, satisfied with getting a joke in and moving on. Yet, like Jerry Seinfeld, Birbiglia’s insights are, if not hysterical, consistently moderately amusing throughout, and seeing him gnaw on a neck pillow made out of pepperoni pizza was enough trigger at least one involuntary guffaw from me. But can Birbiglia make a film career out of such mild stuff? His future as a comic leading man might depend on whether he can be more generous to an ensemble or find a new type of window from which to fall.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

While Sleepwalk with Me struggles to brings its relationships to life, the latest film from director Ira Sachs (The Delta) Keep the Lights On, displays an almost unnerving ability to capture the unspoken dynamics that define romantic relationships. Taking place between the years of 1998 and 2006, Leave the Lights On is a startlingly intimate portrait of two men fucking, falling in love and falling apart, all set to the airy tunes of avant dance musician Arthur Russell. The film’s spare, almost generic story (co-written by Mauricio Zacharias of the 2002 indie hit, Madame Sata) finds its strengths in two un-showy and brilliant performances that achieve a realism that gives the beautiful illusion of witnessing an event as opposed to seeing an event re-enacted.

The couple includes gorgeously scruffy blonde Erik (Thure Lindhardt, from Sean Penn’s Into the Wild), a thirty-something Danish-American documentary filmmaker, living off his parents while he finishes his film on gay  photographer Avery Willard (a project Ira Sachs is actually producing, FYI) Erik cruises phone sex lines and one night he hooks up with handsome preppy Paul (Zachary Booth of TV’s Damages,) an assistant book editor who is slowly extracting himself from a girlfriend. The early sex scenes are the are the sort of sensuous fare that once might have left this film in the gay ghetto, but the universality of the relationship as captured by Sachs and the unstudied depth of the performances give the film a wider appeal. Even when the film falls into an almost cliché plot-turn chronicling Paul’s descent into crack addiction, Sachs focuses on the fear and isolation the situation uncovers rather than the mundane details of the drug life.

photographer Avery Willard (a project Ira Sachs is actually producing, FYI) Erik cruises phone sex lines and one night he hooks up with handsome preppy Paul (Zachary Booth of TV’s Damages,) an assistant book editor who is slowly extracting himself from a girlfriend. The early sex scenes are the are the sort of sensuous fare that once might have left this film in the gay ghetto, but the universality of the relationship as captured by Sachs and the unstudied depth of the performances give the film a wider appeal. Even when the film falls into an almost cliché plot-turn chronicling Paul’s descent into crack addiction, Sachs focuses on the fear and isolation the situation uncovers rather than the mundane details of the drug life.

Paul’s fussy restraint is so vivid, we miss him when he’s gone, as Erik deals with nights and sometime days that Paul does not come home. This leads to a particularly eerie scene when Erik tracks down the delusional Paul to a hotel room, where he ultimately holds his hand while Paul drifts off into his lonely ether. From then on, they both drift together and drift apart, and despite the promises they make to each other it all seems to be part of the process of bringing their relationship to a close.

Julianne Nicholson, once a familiar face on Law and Order: Criminal Intent is on hand to fulfill the best friend role for Erik, but mainly the focus is on the good-looking duo in their quietest moments while they hit every private hairpin turn and drop-off of their roller coaster relationship. One might like this pair or one might find them frustrating, but it is Sach’s open-ended, beautifully scatter-shot style that leaves you with the feeling that they are real people that you’ve gotten to know. Even if there is nothing startlingly new here, the film never feels formulaic or rote, instead feeling alive and in the present, a rare feat in any age.