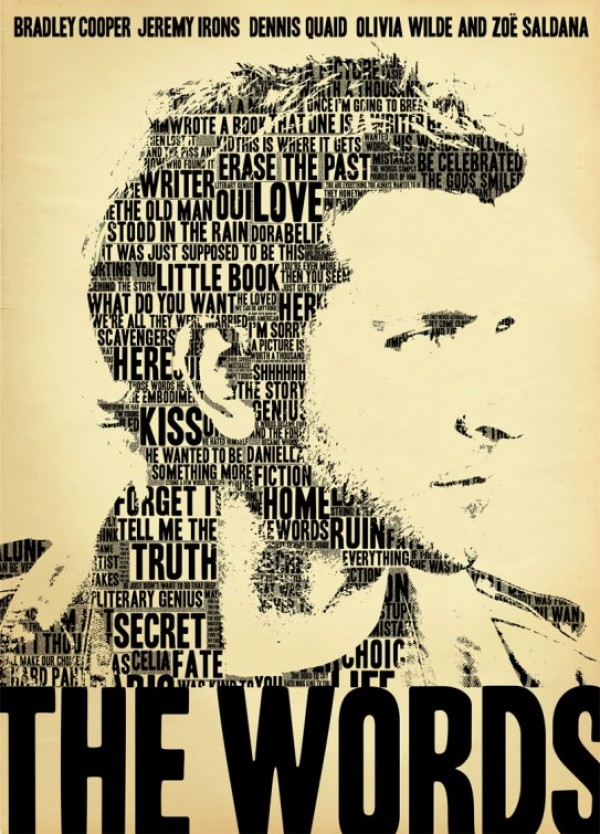

![]() BY BRANDON LAFVING ARTS CORRESPONDENT Bradley Cooper’s new film, The Words, is an artfully meta coming-of-age story that entertains just slightly more than it challenges. Its story pulls our attention through nested narratives of a writer, his book, his characters, the past, present, and every combination of the above, but the journey is rendered effortless by great storytelling. It opens on a book release press event, featuring critically acclaimed novelist Clay Hammond (Dennis Quaid), who reads the first two parts of his new piece, entitled The Words. As the audience of a film rather than a book release party, we are shown a cinematic rendition of the book’s plot.

BY BRANDON LAFVING ARTS CORRESPONDENT Bradley Cooper’s new film, The Words, is an artfully meta coming-of-age story that entertains just slightly more than it challenges. Its story pulls our attention through nested narratives of a writer, his book, his characters, the past, present, and every combination of the above, but the journey is rendered effortless by great storytelling. It opens on a book release press event, featuring critically acclaimed novelist Clay Hammond (Dennis Quaid), who reads the first two parts of his new piece, entitled The Words. As the audience of a film rather than a book release party, we are shown a cinematic rendition of the book’s plot.

There is a struggling writer, Rory Jansen, who has just finished his first novel. Like most novelists in this tenuous position, Jansen struggles to maintain a lifestyle that is as far beyond his financial means as it is beneath the measure of his talent. In this remarkable case, he juggles a New York apartment the size of a baseball diamond and gorgeous fiancé Dora (Zöe Saldana). The pressure is seismic. Continued lack of a willing publisher brings Rory to the tipping point of the movie. He stands against a red brick wall, literally, during an intermittent self-directed tirade/confession. In spite of the clichéd nature of it all, director Lee Sternthal ekes out a complex and vulnerable scene. It never rains, for instance.

More interesting is Cooper himself, who knows how not to act too much. Rather than exploding or sobbing, he plays the frayed edges of an insolvent, letting the tears come weakly from the back of his throat. He admits that he doesn’t know if he will ever become the writer he thought he was. The whole debacle ends unexpectedly with a deft smirk, the exact meaning of which continues to titillate, provoke, and haunt me. Apparently, Cooper is tired of making silly blockbusters, such as The A-Team and The Hangover tripartite series. Rory is a subtle, serious, and – as you will see – duplicitous character.

Soon after his confession, Rory comes to possess a brilliantly written, as-yet unpublished manuscript. As he reads it, we are taken one step further into the rabbit hole, this time, to France in the 40s. There is a beautiful couple – an American soldier and French peasant. They cannot speak more than one word to each other and fall hopelessly in love. The story is deep, evocative, brilliant. It is better than anything Rory could possibly write. Thus, the perfect temptation comes at the perfect time. He retypes the novel and publishes it under his name. He gains money and fame, but there is also a price.

This is no The Hangover, Part 27. The plot is as multilayered as Black Forest Cake. But unlike other recent movies that have attempted to convey similarly complex relations, such as Inception and Avatar, The Words does not resort to CGI to keep its audience involved. On the other hand, the movie does not approach the headiness of Being John Malkovich or Sunlight of the Spotless Mind. It stops in the cinematic middle. The Words is a powerful and well-balanced piece of communication, which moves self-referential cinema forward. What this film communicates may not be new, but the context pushes what has been an intellectual concept one step closer to the human heart. Writer/director Lee Sternthal should be proud (as opposed to his last CGI-reliant work, Tron: Legacy). All the artistically inclined pondlings out there will find plenty in The Words to sink their teeth into and pull from the bone. For everyone else, there is realism and romance.