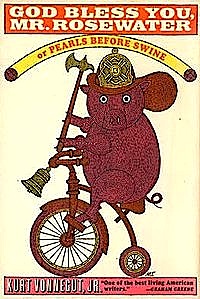

![]() BY DAVID CORBO 1965 was an interesting year in the United States. President Lyndon Johnson introduced the social reforms of his “Great Society”, the first American combat troops landed in South Vietnam, and Martin Luther King marched 25,000 civil rights protesters from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. Bob Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival, The Watts Riots began in LA, and the Beatles played the first rock and roll stadium concert at Shea Stadium. In the midst of all of this, and true to the questioning nature of the times, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., in his best satirical form, published his fifth novel God Bless You Mr. Rosewater, or Pearls Before Swine.

BY DAVID CORBO 1965 was an interesting year in the United States. President Lyndon Johnson introduced the social reforms of his “Great Society”, the first American combat troops landed in South Vietnam, and Martin Luther King marched 25,000 civil rights protesters from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. Bob Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival, The Watts Riots began in LA, and the Beatles played the first rock and roll stadium concert at Shea Stadium. In the midst of all of this, and true to the questioning nature of the times, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., in his best satirical form, published his fifth novel God Bless You Mr. Rosewater, or Pearls Before Swine.

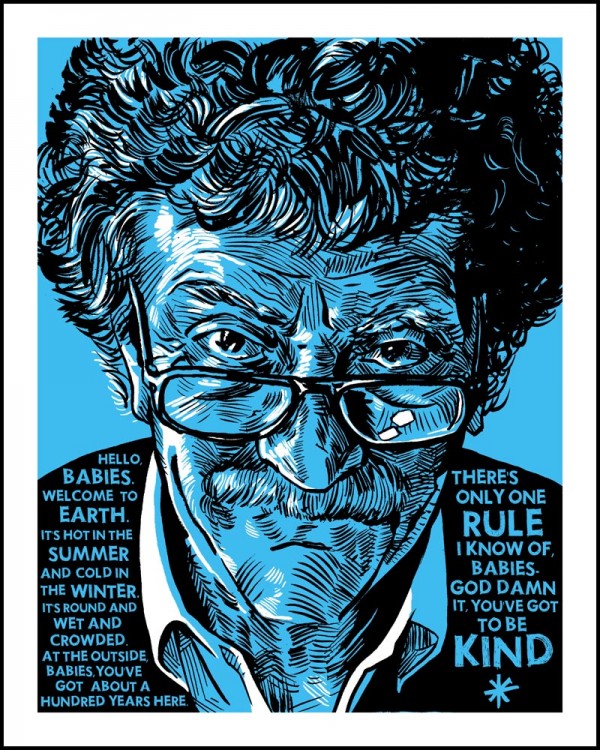

Vonnegut was particularly well suited to critique the social and political issues that defined the tumultuous cultural upheaval of the 1960’s. A leftist intellectual, he was a lifetime member of the American Civil Liberties Union, an honorary president of the American Humanist Association and a proponent of the Socialist philosophies of Eugene Debs whom he was fond of quoting in his novels. As a survivor of the Allied firebombing of Dresden in 1945, where he was interred as a POW, he witnessed firsthand the results of senseless mass slaughter, an event that would forever haunt him and his prose. Vonnegut was fond of saying that the only redemption for the meaninglessness of existence was human kindness, and that kindness is what it’s all about for this book’s flawed protagonist.

At heart, God Bless You Mr. Rosewater is a morality tale about the plutocratic nature of our democracy. The plot revolves around the philanthropic activities of Elliot Rosewater, heir to the Rosewater Foundation, a  tax shelter set up to protect the family fortune by his father, Senator Lister Ames Rosewater of Indiana. Great-grandfather Noah Ames, a farmer turned arms manufacturer at the advent of the Civil War, amassed the Foundation’s wealth through lucrative government contracts, bribery, industrial consolidation and selling watered stock. As Elliot puts it “[t]hus did a handful of rapacious citizens come to control all that was worth controlling in America.”

tax shelter set up to protect the family fortune by his father, Senator Lister Ames Rosewater of Indiana. Great-grandfather Noah Ames, a farmer turned arms manufacturer at the advent of the Civil War, amassed the Foundation’s wealth through lucrative government contracts, bribery, industrial consolidation and selling watered stock. As Elliot puts it “[t]hus did a handful of rapacious citizens come to control all that was worth controlling in America.”

Traumatized by his unwitting involvement in the accidental killing of innocent firemen during his service in WWII, Elliot becomes an alcoholic, unkempt mess. He marries the cultured Parisienne beauty Sylvia DuVrain Zetterling and takes over his inheritance, appalling his senatorial father by becoming a fireman and proceeding to administer everything from financial aid to baptisms to the most destitute of society in Rosewater County, Indiana. Sylvia eventually abandons him without producing an heir, after suffering a mental breakdown diagnosed as a case of “Samaritrophia,” sarcastically defined as “[the] suppression of an overactive conscience by the rest of the mind.” Throughout the novel, Elliot survives attempts by the young lawyer Norman Mushari and distant Rhode Island relatives to wrest control of the Foundation from him. In the end, Elliot retains his riches and proves to be the consummate humanitarian by adopting every child that is “said to be his” in Rosewater County, thus securing the redistribution of the family’s ill-gotten wealth back to the people.

In this election season, where attempts to re-balance the distribution of wealth are constantly attacked as creeping socialism and economically ludicrous, Vonnegut’s sardonic take on the American oligarchy is as relevant today as it was in 1965. Elliot Rosewater may be drunk, damaged and the scourge of his family, but in the end his desire for equality wins out over all the temptations his privileged life has placed before him. Thank you Mr. Vonnegut, and God bless you Mr. Rosewater.