ASSOCIATED PRESS: The baby thefts set Argentina’s military regime apart from all the other juntas that ruled in Latin America at the time. Videla and other military and police officials were determined to remove any trace of the armed leftist guerrilla movement they said threatened the country’s future. Many pregnant women detained as dissidents were “disappeared” shortly after giving birth in clandestine maternity wards, and their babies were handed over to families trusted by military officials. […] Witnesses during the trial included former U.S. diplomat Elliot Abrams. He was called to testify after a long-classified memo describing his secret meeting with Argentina’s ambassador was made public at the request of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, a human rights group whose evidence-gathering efforts were key to the prosecution. Abrams testified from Washington that he secretly urged that Bignone reveal the stolen babies’ identities as a way to smooth Argentina’s return to democracy. “We knew that it wasn’t just one or two children,” Abrams testified, suggesting that there must have been some sort of directive from a high level official — “a plan, because there were many people who were being murdered or jailed.” No reconciliation effort was made. Instead, Bignone ordered the military to destroy evidence of “dirty war” activities, and the junta denied any knowledge of baby thefts, let alone responsibility for the disappearances of political prisoners. The U.S. government also revealed little of what it knew as the junta’s death squads were eliminating opponents. The Grandmothers have since used DNA evidence to help 106 people who were stolen from prisoners as babies recover their true identities, and 26 of these cases were part of this trial. Many were raised by military officials or their allies, who falsified their birth names, trying to remove any hint of their leftist origins. The rights group estimates as many as 500 babies could have been stolen in all, but the destruction of documents and passage of time make it impossible to know for sure. The trial featured gut-wrenching testimony from relatives who searched inconsolably for their missing children, and from people who learned as young adults that they were raised by some of the very people involved in the disappearance of their birth parents. MORE

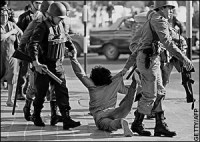

RELATED: The Dirty War (Spanish: Guerra Sucia) was a period of state terrorism in Argentina from 1976 until 1983. Victims of the violence included several thousand left-wing activists and militants, including trade unionists,  students, journalists, Marxists, Peronist guerrillas[1] and alleged sympathizers.[2] Estimates for the number of people who were killed or “disappeared” range from 9,089 to over 30,000;[6][7] the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons estimates that around 13,000 disappeared.[8] However, these figures must be considered inadequate as declassified documents and internal reporting by Argentine military intelligence itself confirm at least 22,000 killed or “disappeared” between late-1975 (several months prior to the March 1976 coup) and mid-July 1978, which is incomplete as it excludes killings and “disappearances” that occurred after July of 1978.[9] MORE

students, journalists, Marxists, Peronist guerrillas[1] and alleged sympathizers.[2] Estimates for the number of people who were killed or “disappeared” range from 9,089 to over 30,000;[6][7] the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons estimates that around 13,000 disappeared.[8] However, these figures must be considered inadequate as declassified documents and internal reporting by Argentine military intelligence itself confirm at least 22,000 killed or “disappeared” between late-1975 (several months prior to the March 1976 coup) and mid-July 1978, which is incomplete as it excludes killings and “disappearances” that occurred after July of 1978.[9] MORE

RELATED: Conservatives, including some among the wealthy elite, encouraged the army, which prepared to take control by making lists of people who should be “dealt with” after the planned coup. In 1975, President Isabel Perón, under pressure from the military establishment, appointed Jorge Rafael Videla commander-in-chief of the Argentine Army. “As many people as necessary must die in Argentina so that the country will again be secure”, Videla declared in 1975 in support of the death squads. He was one of the military heads of the coup d’état that overthrew Isabel Perón on 24 March 1976. MORE

RELATED: State Department documents obtained by the National Security Archive under the Freedom of Information Act show that in October 1976, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and high-ranking U.S. officials gave their full  support to the Argentine military junta and urged them to hurry up and finish the “dirty war” before the U.S. Congress cut military aid.[155] The U.S. was also a key provider of economic and military assistance to the Videla regime during the earliest and most intense phase of the repression. In early April 1976, the U.S. Congress approved a request by the Ford Administration, written and supported by Henry Kissinger, to grant $50,000,000 in security assistance to the junta.[156] At the end of 1976, Congress granted an additional $30,000,000 in military aid, and recommendations by the Ford Administration to increase military aid to $63,500,000 the following year were also considered by congress.[157] U.S. assistance, training and military sales to the Videla regime continued under the successive Carter Administration up until at least September 30, 1978 when military aid was officially called to a stop within section 502B of the Foreign Assistance Act. In 1977 and 1978 the United States sold more than $120,000,000 in military spare parts to Argentina, and in 1977 the US Department of Defense was granted $700,000 to train 217 Argentinian military officers.[158] By the time the International Military Education and Training (IMET) program was suspended to Argentina in 1978, total US training costs for Argentinian military personnel since 1976 totaled $1,115,000. After the onset of the US military cutoff, Israel became Argentina’s principle supplier of weapons.[159] The Reagan Administration, whose first term began in 1981, however, asserted that the previous Carter Administration had weakened US diplomatic relationships with Cold War allies in Argentina, and reversed the previous administration’s official condemnation of the junta’s human rights practices. MORE

support to the Argentine military junta and urged them to hurry up and finish the “dirty war” before the U.S. Congress cut military aid.[155] The U.S. was also a key provider of economic and military assistance to the Videla regime during the earliest and most intense phase of the repression. In early April 1976, the U.S. Congress approved a request by the Ford Administration, written and supported by Henry Kissinger, to grant $50,000,000 in security assistance to the junta.[156] At the end of 1976, Congress granted an additional $30,000,000 in military aid, and recommendations by the Ford Administration to increase military aid to $63,500,000 the following year were also considered by congress.[157] U.S. assistance, training and military sales to the Videla regime continued under the successive Carter Administration up until at least September 30, 1978 when military aid was officially called to a stop within section 502B of the Foreign Assistance Act. In 1977 and 1978 the United States sold more than $120,000,000 in military spare parts to Argentina, and in 1977 the US Department of Defense was granted $700,000 to train 217 Argentinian military officers.[158] By the time the International Military Education and Training (IMET) program was suspended to Argentina in 1978, total US training costs for Argentinian military personnel since 1976 totaled $1,115,000. After the onset of the US military cutoff, Israel became Argentina’s principle supplier of weapons.[159] The Reagan Administration, whose first term began in 1981, however, asserted that the previous Carter Administration had weakened US diplomatic relationships with Cold War allies in Argentina, and reversed the previous administration’s official condemnation of the junta’s human rights practices. MORE

RELATED: Many of the victims were so weak from torture and detention that they had to be helped aboard the plane. Once in flight, they were injected with a sedative by an Argentine Navy doctor before two officers stripped them  and shoved them to their deaths. Now, one of those officers has acknowledged that he pushed 30 prisoners out of planes flying over the Atlantic Ocean during the right-wing military Government’s violent crackdown in the 1970’s. The former officer, Adolfo Francisco Scilingo, 48, a retired navy commander, became the first Argentine military man to provide details of how the military dictatorship then in power disposed of hundreds of kidnapping and torture victims of what was known as the dirty war by dumping them, unconscious but alive, into the ocean from planes. MORE

and shoved them to their deaths. Now, one of those officers has acknowledged that he pushed 30 prisoners out of planes flying over the Atlantic Ocean during the right-wing military Government’s violent crackdown in the 1970’s. The former officer, Adolfo Francisco Scilingo, 48, a retired navy commander, became the first Argentine military man to provide details of how the military dictatorship then in power disposed of hundreds of kidnapping and torture victims of what was known as the dirty war by dumping them, unconscious but alive, into the ocean from planes. MORE

RELATED: Imagine the scene. Men and women are drugged, stripped naked and then dragged aboard aeroplanes, before being pushed out into the ocean and plunging to their deaths in the cold waters of the Atlantic. In an added twist of horrific cruelty, some of the victims are falsely told that they are in fact being released from their imprisonment and that they should dance in joy and celebration of their imminent release. Speaking in an interview in 1996, Scilingo said “They were played lively music and made to dance for joy, because they were going to be transferred to the south… After that, they were told they had to be vaccinated due to the transfer, and they were injected with Pentothal. And shortly after, they became really drowsy, and from there we loaded them onto trucks and headed off for the airfield.” MORE

RELATED: He estimated that the navy conducted the flights every Wednesday for two years, 1977 and 1978, and that 1,500 to 2,000 people were killed. He said that after his first flight, in which he slipped and almost fell through the  portal from which he was throwing bodies, he became so distraught that he confessed his actions to a military priest, who absolved him, saying the killings “had to be done to separate the wheat from the chaff.” He went on: “When we finished dumping the bodies, we closed the door to the plane, it was quiet, and all that was left was the clothing which was taken back and thrown away. I went home that night and had two glasses of whiskey and went to sleep.” Asked to describe the second mission, in which he said he dumped 17 people into the ocean, Mr. Scilingo said he could no longer discuss the details because he was about to break down. “I have spent many nights sleeping in the plazas of Buenos Aires with a bottle of wine, trying to forget,” he said. “I have ruined my life. I have to have the radio or television on at all times or something to distract me. Sometimes I am afraid to be alone with my thoughts.” MORE

portal from which he was throwing bodies, he became so distraught that he confessed his actions to a military priest, who absolved him, saying the killings “had to be done to separate the wheat from the chaff.” He went on: “When we finished dumping the bodies, we closed the door to the plane, it was quiet, and all that was left was the clothing which was taken back and thrown away. I went home that night and had two glasses of whiskey and went to sleep.” Asked to describe the second mission, in which he said he dumped 17 people into the ocean, Mr. Scilingo said he could no longer discuss the details because he was about to break down. “I have spent many nights sleeping in the plazas of Buenos Aires with a bottle of wine, trying to forget,” he said. “I have ruined my life. I have to have the radio or television on at all times or something to distract me. Sometimes I am afraid to be alone with my thoughts.” MORE