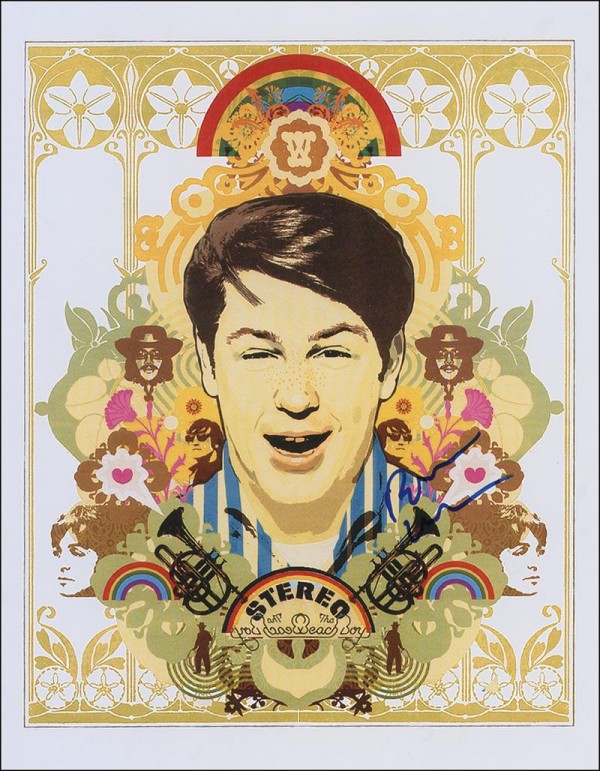

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA Teenage symphonies to God. That’s the phrase Beach Boys auteur Brian Wilson used to describe the a heartbreaking works of staggering genius he was creating in the mid-’60s, when his compositional powers were achieving miraculous states of beauty and innovation even as his fevered faculties skirted the fringes of madness. With the 1966 release of Pet Sounds, The Beach Boy’s orchestral-pop opus of ocean-blue melancholia, Brian clinched his status as teen America’s Mozart-on-the-beach in the cosmology of modern pop music.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Teenage symphonies to God. That’s the phrase Beach Boys auteur Brian Wilson used to describe the a heartbreaking works of staggering genius he was creating in the mid-’60s, when his compositional powers were achieving miraculous states of beauty and innovation even as his fevered faculties skirted the fringes of madness. With the 1966 release of Pet Sounds, The Beach Boy’s orchestral-pop opus of ocean-blue melancholia, Brian clinched his status as teen America’s Mozart-on-the-beach in the cosmology of modern pop music.

Less than a year later, he would fall off the edge of his mind, abandoning his ambitious LSD-inspired follow-up, an album with the working title Dumb Angel later changed to Smile, which many who were privy to the recording sessions claimed would change the course of music history. Instead, it was The Beatles who would, as the history books tell us, assume the mantle of culture-shifting visionaries with Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released a few months after Wilson pulled the plug on Smile. Meanwhile, Wilson sank into a decades-long downward spiral of darkness, exiling himself to a bedroom hermitage of terrifying hallucinations, debilitating paranoia, Herculean drug abuse and morbid obesity. While he would later recover some measure of his sanity, he would never again craft a work of such overarching majesty.

In the wake of all the breathless hype for an album that was never finished, Smile took on mythical status, and a cult of Wilsonian acolytes sprang up as fellow  musicians and super-fans tried to connect the dots into constellations and piece together a completed album from the bootlegs of recording session outtakes that have leaked out over the years. For decades, Wilson maintained a Sphinx-like silence, unwilling or unable to talk about the project, which only amped up the mystery surrounding the project. But given its central role in his precipitous downfall, it’s no wonder Wilson refused to even discuss Smile in interviews, let alone entertain repeated entreaties to finish and release it. Furthermore, he no longer had the Beach Boys’ golden throats to carry his tunes — brothers Carl and Dennis are deceased and his relationship with cousin Mike Love has devolved into acrimony and six-figure litigation.

musicians and super-fans tried to connect the dots into constellations and piece together a completed album from the bootlegs of recording session outtakes that have leaked out over the years. For decades, Wilson maintained a Sphinx-like silence, unwilling or unable to talk about the project, which only amped up the mystery surrounding the project. But given its central role in his precipitous downfall, it’s no wonder Wilson refused to even discuss Smile in interviews, let alone entertain repeated entreaties to finish and release it. Furthermore, he no longer had the Beach Boys’ golden throats to carry his tunes — brothers Carl and Dennis are deceased and his relationship with cousin Mike Love has devolved into acrimony and six-figure litigation.

Meanwhile, even with Wilson‘s protracted absence from the music scene, the dark legend of Smile was passed down via oral tradition and backroom-traded bootlegs to succeeding generations of pop obsessives, scholars and composers and hailed by many as the enigmatic “Rosebud” of popular music. Selected tracks from the Smile sessions — spectral, spooky, ineffably beautiful — released with 1994?s Good Vibrations box set only fanned the flames of obsession and lurid speculation. Like the mysterious leopard found frozen to death near the summit of the mountain in Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” everyone wanted to know how Wilson got that high and what exactly he was looking for up there.

Aided by the radical interventions of psychiatrists and a cornucopia of mood-altering and anti-psychotic medications — not to mention an empathetic support network of friends, family and business associates — Brian has staged an impressive comeback despite that fact that he remains a very damaged soul. For the last decade, he has delivered moving concert performances with an exceptionally fluent 10-piece band of new-school L.A. scenesters that is capable of replicating the sunbeam glories of those Beach Boys harmonies and recreating the orchestral pop glories of Pet Sounds down to the last ornate sonic detail.

The, in 2004, Brian shocked the music world with the announcement that he had finally completed his lost masterpiece with the aid of this crack touring band, re-recording the vocals and backing tracks and completing, with the help of his Smile-era lyricist Van Dyke Parks, the project’s half-finished songs. As welcome as news of this development was to Smile buffs, the end result was somehow less-than-completely-satisfying, like visiting a replica of an historic artifact in a museum (Not the actual bed that George Washington slept in, but an incredible facsimile!) The critical response was fawning, but smacked of the over-praise usually reserved for special Olympians, and as such ultimately fleeting.Which is why the five CD box set The Smile Sessions will be the final word on Smile, separating once and for all rumor from fact, solving old mysteries, cracking the riddles of incompletion and providing closure for those that have pondered and puzzled over Smile’s tragicomic legend for the last 44 years. Relying on cutting edge digital technology to assemble, assess and edit together the best and brightest moments buried in the more than 30 hours of Smile work tapes — which was a fool’s errand in the razor-and-scotch-tape analog era — and using the 2004 re-do as a guide for song selection and sequence, engineers Mark Linnett and Alan Boyd have assembled the closest we will ever come to a completed Smile on Disc One.

The, in 2004, Brian shocked the music world with the announcement that he had finally completed his lost masterpiece with the aid of this crack touring band, re-recording the vocals and backing tracks and completing, with the help of his Smile-era lyricist Van Dyke Parks, the project’s half-finished songs. As welcome as news of this development was to Smile buffs, the end result was somehow less-than-completely-satisfying, like visiting a replica of an historic artifact in a museum (Not the actual bed that George Washington slept in, but an incredible facsimile!) The critical response was fawning, but smacked of the over-praise usually reserved for special Olympians, and as such ultimately fleeting.Which is why the five CD box set The Smile Sessions will be the final word on Smile, separating once and for all rumor from fact, solving old mysteries, cracking the riddles of incompletion and providing closure for those that have pondered and puzzled over Smile’s tragicomic legend for the last 44 years. Relying on cutting edge digital technology to assemble, assess and edit together the best and brightest moments buried in the more than 30 hours of Smile work tapes — which was a fool’s errand in the razor-and-scotch-tape analog era — and using the 2004 re-do as a guide for song selection and sequence, engineers Mark Linnett and Alan Boyd have assembled the closest we will ever come to a completed Smile on Disc One.

Discs Two, Three and Four assembles rehearsal work tapes, embryonic early takes and alternate versions of the songs on Disc One. These outtakes are fascinating for the range of experimentation and innovation attempted here, as well the telling snippets of dialogue (“Are you guys feeling the acid yet?” Brian asks during an early run  through the Gregorian chant of “Our Prayer”). Disc 5 contains 24 versions of “Good Vibrations,” enabling the listener to hear its evolution from quasi-R&B stomper to the trippy pocket-sized symphony that plays in perpetuity on oldies radio. Recorded over the course of nine months in three studios at a cost of $40,000 the song was at the time the most expensive single ever made. Serving as a bridge between Pet Sounds and Smile, “Good Vibrations” marks the beginning of Brian’s use of the modular composition technique that made the song both a deathless classic and an intimation of Smile’s impending doom. Instead of tracking songs from beginning to end as he did on Pet Sounds, Brian recorded and re-recorded an endless series of interchangeable sonic segments that would be jigsawed together at the end. This technique would prove doable but daunting in the digital era — where point-and-click technology enabled the engineers to time travel back and forth across hours and hours of recording sessions in mere seconds and edit together otherwise incongruent musical passages with relative ease — but epic, laborious and, quite literally, crazy-making in the low-tech analog era of the late 1960s. In that sense, Smile was way ahead of its time, as Brian and his acolytes always claimed, if only because the technology needed to complete it simply didn’t exist in 1967.

through the Gregorian chant of “Our Prayer”). Disc 5 contains 24 versions of “Good Vibrations,” enabling the listener to hear its evolution from quasi-R&B stomper to the trippy pocket-sized symphony that plays in perpetuity on oldies radio. Recorded over the course of nine months in three studios at a cost of $40,000 the song was at the time the most expensive single ever made. Serving as a bridge between Pet Sounds and Smile, “Good Vibrations” marks the beginning of Brian’s use of the modular composition technique that made the song both a deathless classic and an intimation of Smile’s impending doom. Instead of tracking songs from beginning to end as he did on Pet Sounds, Brian recorded and re-recorded an endless series of interchangeable sonic segments that would be jigsawed together at the end. This technique would prove doable but daunting in the digital era — where point-and-click technology enabled the engineers to time travel back and forth across hours and hours of recording sessions in mere seconds and edit together otherwise incongruent musical passages with relative ease — but epic, laborious and, quite literally, crazy-making in the low-tech analog era of the late 1960s. In that sense, Smile was way ahead of its time, as Brian and his acolytes always claimed, if only because the technology needed to complete it simply didn’t exist in 1967.

But a few listens to the songs on Disc One would cause any neutral observer with a functioning pair functioning pair of ears to conclude that this music was way ahead its time sonically and thematically — a cinematic travelogue narrated by a psychedelic barbershop quartet fronting a cosmic Salvation Army Band, mapping the birth of a nation, the westward expansion of manifest destiny from Plymouth Rock to blue Hawaii, evoking all the weirdness and whimsy, the laughter and the tears, the triumph and tragedy in between — because it still sounds thoroughly modern, and for that matter altogether mind blowing, 44 years after its stillborn inception.