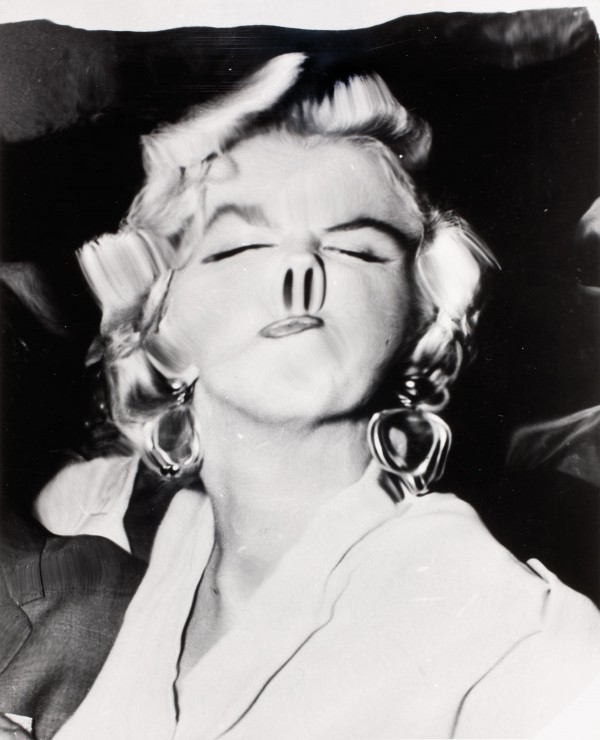

ART NEWS: When Arthur Fellig, the New York street photographer known as Weegee, moved to Los Angeles in 1947 to become a technical adviser on The Naked City, the film-noir classic named after his 1945 book of photos, he had big Hollywood dreams. Like many aspiring stars before and after, he didn’t quite find the magical landscape of the movies, and he declared that Hollywood was Newark, New Jersey, with palm trees. Weegee was famous in New York for grisly crime-scene photos. He earned his nickname from his job as a darkroom assistant, or “squeegee boy,” for the New York Times or perhaps from his Ouija board–like knack for predicting events—he would show up immediately after fires, suicides, and murders (no doubt with help from his portable police-band radio). This street sensibility influenced his L.A. photos as well. “Instead of just photographing the stars, he photographed all of the people waiting for the stars along Hollywood Boulevard,” says Meyer, “including their awestruck expressions when the stars arrived or their crestfallen emotions when they don’t get an autograph they’ve been waiting hours for.” While other photographers clambered for straight-ahead shots of Grace Kelly and Joan Crawford, Weegee turned his lens on signs for pawnshops and funeral parlors. “In his own fairly dark way, he’s trying to make a commentary about the gap between Hollywood fantasy and the reality of fandom,” Meyer says. He would also take photos of stars with food in their mouths and distorted portraits shot with an elastic lens. MORE

RELATED: For an intense decade between 1935 and 1946, Weegee (1899–1968) was one of the most relentlessly inventive  figures in American photography. His graphically dramatic and often lurid photographs of New York crimes and news events set the standard for what has become known as tabloid journalism. Freelancing for a variety of New York newspapers and photo agencies, and later working as a stringer for the short-lived liberal daily PM (1940–48), Weegee established a way of combining photographs and texts that was distinctly different from that promoted by other picture magazines, such as LIFE. Utilizing other distribution venues, Weegee also wrote extensively (including his autobiographical Naked City, published in 1945) and organized his own exhibitions at the Photo League. This exhibition draws upon the extensive Weegee Archive at ICP and includes environmental recreations of Weegee’s apartment and exhibitions. MORE

figures in American photography. His graphically dramatic and often lurid photographs of New York crimes and news events set the standard for what has become known as tabloid journalism. Freelancing for a variety of New York newspapers and photo agencies, and later working as a stringer for the short-lived liberal daily PM (1940–48), Weegee established a way of combining photographs and texts that was distinctly different from that promoted by other picture magazines, such as LIFE. Utilizing other distribution venues, Weegee also wrote extensively (including his autobiographical Naked City, published in 1945) and organized his own exhibitions at the Photo League. This exhibition draws upon the extensive Weegee Archive at ICP and includes environmental recreations of Weegee’s apartment and exhibitions. MORE

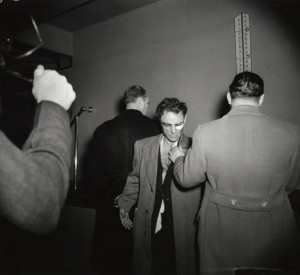

NEW YORK TIMES: Steps away from the sanitized, commercialized and pacified Times Square is a portal to a sinister urban past, where two-bit hoods lay sprawled in pools of blood with stogies clenched in their lifeless jaws, watched over by the police and the curious alike. It’s a world of men with guns and hats who played their final hands under elevated tracks and tenements that have long since vanished. A sprawling show devoted to an intense decade in the city’s history opens Friday at the International Center of  Photography. “Weegee: Murder Is My Business” delivers on its promise, and then some, showcasing the work of the legendary photographer Arthur Fellig from 1935 to 1946. He had a knack for being in the right place at the right time. More importantly, he had a unique visual style – like in his photo of a Little Italy homicide titled “Balcony Seats at a Murder.” Transcending the just-the-facts approach of routine police crime scene photography, he captured the details and drama, the humor and the horror, along the city’s streets. Though some images turn on sight gags and ironic puns, there are many more that show an unmatched and unsentimental feel for the streets and its denizens. While Weegee could be equal parts huckster and hustler, he was also dedicated to his work, said Brian Wallis, the show’s curator. “One of the things we wanted to correct with this show was that view of him as a naïf or a buffoon, who just happened to take pictures,” he said. “He was a serious and well-respected photographer who worked in a tradition that was denigrated as tabloid photography. He didn’t know the world of museums and galleries, but he did know one thing very well: the streets of New York. He took that seriously.” Strains of jazz and police sirens waft through the center’s galleries, where visitors descend a staircase, under a replica of the big gun sign that marked where Weegee once lived — across Center Street from the old police headquarters. It leads to a re-creation – tidied and spartan – of his old room, down to the scanner, tear sheets and can of bed bug killer. You can almost smell the cigar smoke – though in the city today, that now passes for a crime in most places. The re-creation of his room is fitting for a man who sort of created himself. Mr. Wallis explained how Weegee had seen himself as a photo detective, inhabiting the world of cops and journalists. MORE

Photography. “Weegee: Murder Is My Business” delivers on its promise, and then some, showcasing the work of the legendary photographer Arthur Fellig from 1935 to 1946. He had a knack for being in the right place at the right time. More importantly, he had a unique visual style – like in his photo of a Little Italy homicide titled “Balcony Seats at a Murder.” Transcending the just-the-facts approach of routine police crime scene photography, he captured the details and drama, the humor and the horror, along the city’s streets. Though some images turn on sight gags and ironic puns, there are many more that show an unmatched and unsentimental feel for the streets and its denizens. While Weegee could be equal parts huckster and hustler, he was also dedicated to his work, said Brian Wallis, the show’s curator. “One of the things we wanted to correct with this show was that view of him as a naïf or a buffoon, who just happened to take pictures,” he said. “He was a serious and well-respected photographer who worked in a tradition that was denigrated as tabloid photography. He didn’t know the world of museums and galleries, but he did know one thing very well: the streets of New York. He took that seriously.” Strains of jazz and police sirens waft through the center’s galleries, where visitors descend a staircase, under a replica of the big gun sign that marked where Weegee once lived — across Center Street from the old police headquarters. It leads to a re-creation – tidied and spartan – of his old room, down to the scanner, tear sheets and can of bed bug killer. You can almost smell the cigar smoke – though in the city today, that now passes for a crime in most places. The re-creation of his room is fitting for a man who sort of created himself. Mr. Wallis explained how Weegee had seen himself as a photo detective, inhabiting the world of cops and journalists. MORE