It’s called Centipede HZ. DEVELOPING…

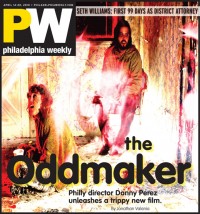

RELATED: At turns disturbing, confusing, disgusting, hilarious, mesmerizing and stone cold beatific, Oddsac is perhaps best explained by clarifying what it is not: it is neither a rock documentary nor a concert film, nor is it the kind of film you would see at the cineplex. There are no stars, no car chases, no dreamy romantic interests who meet cute and live happily ever after. In fact, there is no plot, no linear narrative arc. Instead, there is a series of  hallucinatory vignettes: a girl attempting in vain to stanch the flow of black goo oozing out of the walls of her home; a sad-sack vampire (played by AC’s Josh Dibb) slowly disintegrating at sunrise after preying on a young boy; an ominous procession of fire spinners led by a gibberish-spouting demon (played by AC’s Dave Porter); a wigged-out drummer boy (played by AC’s Noah Lennox) maniacally beating on his kit in the middle of an eerie boulder field; a bearded blue-hued muscle man (played by AC’s Brian Weitz) harvesting mysterious eggs from beneath a waterfall; a nuclear family sitting around the camp fire suddenly projectile vomiting foamy marshmallow goo; and it all ends with a food fight. These images are buffered by Perez’s arresting visual abstractions and framed by an untitled set of Animal Collective songs created for the movie. As for the music, Oddsac finds the band continuing to move away from the rhomboidal Fugsian folk-rock of their early albums while eschewing the iridescent dance music of Merriweather. It is a song cycle cued and composed to the visuals, and as such it is both darker and brighter, more heaven and hell, than anything they have released to date. As cinema, Oddsac is nothing short of remarkable—a mind-fucking eyegasm for people who like that kind of thing. As for what it all means, well, you are at odds with the film’s purpose by even asking. MORE

hallucinatory vignettes: a girl attempting in vain to stanch the flow of black goo oozing out of the walls of her home; a sad-sack vampire (played by AC’s Josh Dibb) slowly disintegrating at sunrise after preying on a young boy; an ominous procession of fire spinners led by a gibberish-spouting demon (played by AC’s Dave Porter); a wigged-out drummer boy (played by AC’s Noah Lennox) maniacally beating on his kit in the middle of an eerie boulder field; a bearded blue-hued muscle man (played by AC’s Brian Weitz) harvesting mysterious eggs from beneath a waterfall; a nuclear family sitting around the camp fire suddenly projectile vomiting foamy marshmallow goo; and it all ends with a food fight. These images are buffered by Perez’s arresting visual abstractions and framed by an untitled set of Animal Collective songs created for the movie. As for the music, Oddsac finds the band continuing to move away from the rhomboidal Fugsian folk-rock of their early albums while eschewing the iridescent dance music of Merriweather. It is a song cycle cued and composed to the visuals, and as such it is both darker and brighter, more heaven and hell, than anything they have released to date. As cinema, Oddsac is nothing short of remarkable—a mind-fucking eyegasm for people who like that kind of thing. As for what it all means, well, you are at odds with the film’s purpose by even asking. MORE

PREVIOUSLY: Back in college, which was longer ago than I care to admit, so let’s just say some time after the Earth cooled but before the Internet, I lived in an old Victorian house that the college owned and subdivided into separate apartments. It was a gathering house for all the freaks and geeks who didn’t quite blend in with the frat-boy-cheerleader-chug-a-lug-date-rape ethos of the main campus. Across the hall my neighbors had set up a de facto commune of 24/7 hacky-sack drum-circling and druggy bird-dogging. Most of the guys living there weren’t even enrolled. They all had sophomoric stoner-rific nicknames — Andy Crack, Stinker, Wild Bill, Bleep — and they all looked like they lived underwater.

Almost nobody knew how to play an instrument, but these guys were gonna start a band. ‘Whatever you say, Hippie Pants,’ I thought to myself. They were gonna call themselves the Gooney Birds after the sheet of primo blotter they’d scored at a recent Dead show. While I went to classes, these guys woodshedded day and night, nourished only by an Evian bottle filled to the brim with liquid LSD. By the end of the semester the bottle was empty and these guys were making some of the most jaw-droppingly mesmerizing folk-based psych I’d ever heard. They sounded like the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey looks. Fuck me, I thought. It’s like they mutated a couple steps up the food chain.

Almost nobody knew how to play an instrument, but these guys were gonna start a band. ‘Whatever you say, Hippie Pants,’ I thought to myself. They were gonna call themselves the Gooney Birds after the sheet of primo blotter they’d scored at a recent Dead show. While I went to classes, these guys woodshedded day and night, nourished only by an Evian bottle filled to the brim with liquid LSD. By the end of the semester the bottle was empty and these guys were making some of the most jaw-droppingly mesmerizing folk-based psych I’d ever heard. They sounded like the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey looks. Fuck me, I thought. It’s like they mutated a couple steps up the food chain.

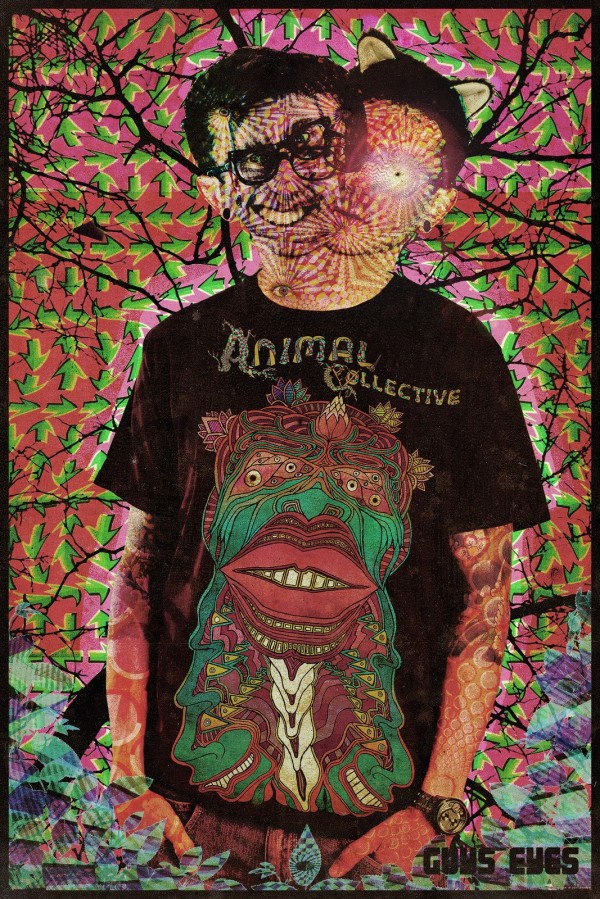

I can’t help but think something similar happened to the men of Animal Collective during their formative years. They’ve known each other since high school. They all have stoner-rific nicknames: Panda Bear, Avey Tare, Geologist, Deaken. From the sound of things, I wouldn’t be surprised to learn they too had a private stock of that Evian elixir when they first took up instruments. Nine albums into their career, Animal Collective have become a cause celebre among the freak-folk meritocracy, creating some of the most stunningly original and indescribably otherworldly music since, well, the acid hit the punk rock some time around the Meat Puppets’ Up on the Sun and Husker Du’s Flip Your Wig.

When it comes to pedigree, Animal Collective cover their paw tracks with six degrees of sonic separation, mutating sound over and over again until it sounds quite ordinary — if you live on Neptune. And they have two great tricks that can’t be easily dismissed: First, they somehow make music that continues to morph even when it’s set in stone on CD. (I’ve listened to Feels about 18 times, and I swear to God not one nanosecond of it ever sounds the same twice.) Second, their unwavering refusal to be serious is what makes them so profound. — JONATHAN VALANIA