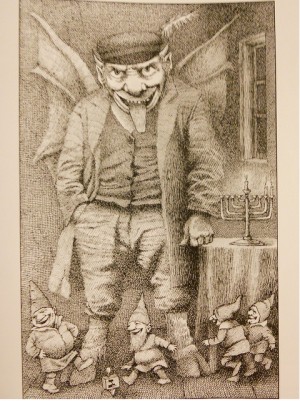

PHAWKER: Where The Wild Things Are creator Maurice Sendak is, in many ways, the dark side Doppelganger of Dr. Seuss and taken together they represent the twin titans of 20th Century children’s literature. If Dr. Seuss’ work vibes like a drug-free acid trip for children aged 8 to 80, then Sendak’s oeuvre is, to extend the metaphor, like Vicodin for the soul, numbing tender-aged psyches from the pain of growing up in a desultory world of de-saturated colors and unrelieved melancholia where adults do monstrous things to each other, and sometimes to children, too. There were two formative experiences in the 84-year-old Sendak’s childhood that imprinted indelibly on his being and have haunted his work for more than 60 years. The first was the mysterious kidnapping and brutal murder of Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., the 18-month-old toddler scion of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh. The second was The Holocaust, where six million men, women and children were exterminated for the crime of believing in the wrong god. Intimations of these horrors can be found in Sendak’s illustrations for the Holocaust-themed Brundibar, his 2003 collaboration with Tony Kushner, and Outside Over There, Sendak’s 1981 story about a young girl named Ida who has to rescue her baby sister after she is stolen away in the night by goblins. MORE

NPR: Maurice Sendak, the children’s book author and illustrator who saw the sometimes-dark side of childhood in books like “Where the Wild Things Are” and “In the Night Kitchen,” died early Tuesday. He was 83. “Where the Wild Things Are” earned Sendak a prestigious Caldecott Medal for the best children’s book of 1964 and became a hit movie in 2009. President Bill Clinton awarded Sendak a National Medal of the Arts in 1996 for his vast portfolio of work. Sendak didn’t limit his career to a safe and successful formula of conventional children’s books, though it was the pictures he did for wholesome works such as Ruth Krauss’ “A Hole Is To Dig” and Else Holmelund Minarik’s “Little Bear” that launched his career. “Where the Wild Things Are,” about a boy named Max who goes on a journey — sometimes a rampage — through his own imagination after he is sent to bed without supper, was quite controversial when it was published, and his quirky and borderline scary illustrations for E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “Nutcracker” did not have the sugar coating featured in other versions. Sendak also created costumes for ballets and staged operas, including the Czech opera “Brundibar,” which he also put on paper with collaborator Pulitzer-winning playwright Tony Kushner in 2003. But despite his varied resume, Sendak accepted — and embraced — the label “kiddie-book author.” “I write books as an old man, but in this country you have to be categorized, and I guess a little boy swimming in the nude in a bowl of milk (as in ‘In the Night Kitchen’) can’t be called an adult book,” he told The Associated Press in 2003. “So I write books that seem more suitable for children, and that’s OK with me. They are a better audience and tougher critics. Kids tell you what they think, not what they think they should  think.” When director Spike Jonez made the movie version of “Where the Wild Things Are,” Sendak said he urged the director to remember his view that childhood isn’t all sweetness and light. And he was happy with the result. “In plain terms, a child is a complicated creature who can drive you crazy” Sendak told the AP in 2009. “There’s a cruelty to childhood, there’s an anger. And I did not want to reduce Max to the trite image of the good little boy that you find in too many books.” Sendak’s own life was clouded by the shadow of the Holocaust. He had said that the events of World War II were the root of his raw and honest artistic style. MORE

think.” When director Spike Jonez made the movie version of “Where the Wild Things Are,” Sendak said he urged the director to remember his view that childhood isn’t all sweetness and light. And he was happy with the result. “In plain terms, a child is a complicated creature who can drive you crazy” Sendak told the AP in 2009. “There’s a cruelty to childhood, there’s an anger. And I did not want to reduce Max to the trite image of the good little boy that you find in too many books.” Sendak’s own life was clouded by the shadow of the Holocaust. He had said that the events of World War II were the root of his raw and honest artistic style. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: In book after book, Mr. Sendak upended the staid, centuries-old tradition of American children’s literature, in which young heroes  and heroines were typically well scrubbed and even better behaved; nothing really bad ever happened for very long; and everything was tied up at the end in a neat, moralistic bow. Mr. Sendak’s characters, by contrast, are headstrong, bossy, even obnoxious. (In “Pierre,” “I don’t care!” is the response of the small eponymous hero to absolutely everything.) His pictures are often unsettling. His plots are fraught with rupture: children are kidnapped, parents disappear, a dog lights out from her comfortable home. A largely self-taught illustrator, Mr. Sendak was at his finest a shtetl Blake, portraying a luminous world, at once lovely and dreadful, suspended between wakefulness and dreaming. In so doing, he was able to convey both the propulsive abandon and the pervasive melancholy of children’s interior lives. His visual style could range from intricately crosshatched scenes that recalled 19th-century prints to airy watercolors reminiscent of Chagall to bold, bulbous figures inspired by the comic books he loved all his life, with outsize feet that the page could scarcely contain. He never did learn to draw feet, he often said. MORE

and heroines were typically well scrubbed and even better behaved; nothing really bad ever happened for very long; and everything was tied up at the end in a neat, moralistic bow. Mr. Sendak’s characters, by contrast, are headstrong, bossy, even obnoxious. (In “Pierre,” “I don’t care!” is the response of the small eponymous hero to absolutely everything.) His pictures are often unsettling. His plots are fraught with rupture: children are kidnapped, parents disappear, a dog lights out from her comfortable home. A largely self-taught illustrator, Mr. Sendak was at his finest a shtetl Blake, portraying a luminous world, at once lovely and dreadful, suspended between wakefulness and dreaming. In so doing, he was able to convey both the propulsive abandon and the pervasive melancholy of children’s interior lives. His visual style could range from intricately crosshatched scenes that recalled 19th-century prints to airy watercolors reminiscent of Chagall to bold, bulbous figures inspired by the comic books he loved all his life, with outsize feet that the page could scarcely contain. He never did learn to draw feet, he often said. MORE