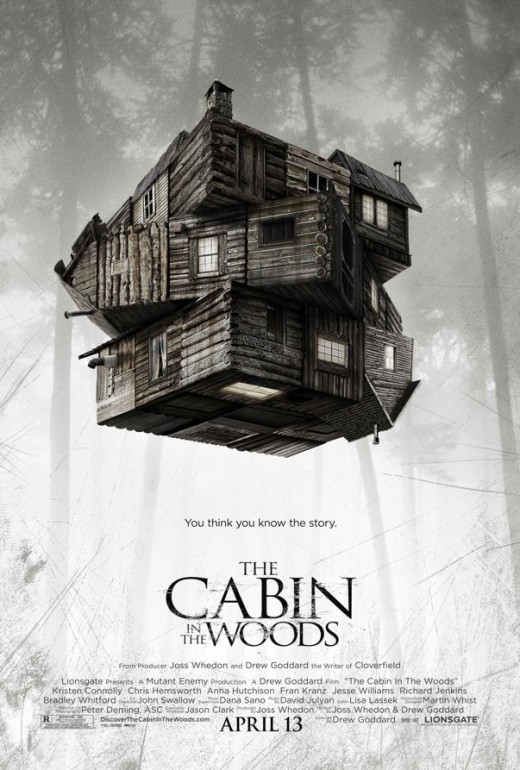

CABIN IN THE WOODS (2011, directed by Drew Goddard, 105 minutes, U.S.)

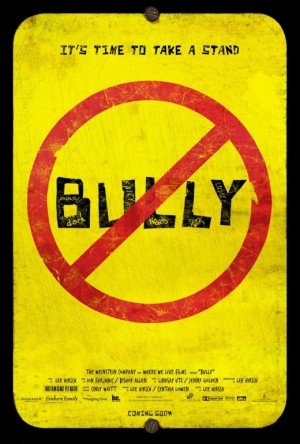

BULLY (2012, directed by Lee Hirsch, 90 minutes, U.S.)

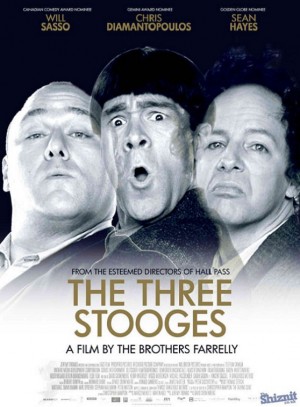

THE THREE STOOGES (2012, directed by Bobby & Peter Farrelly, 92 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC The buzz has been reverberating for a while about Cabin in the Woods, the rare literate, fresh take on the horror genre, and one that is rife with surprises. We don’t need to discuss those surprises to discuss the film, but from the opening scenes we know that the five young college students (two couples and a goofy sidekick) who are headed to a rural cabin are somehow connected to a pair of bantering government workers (Richard Jenkins & Bradley Whitford) who seem a little too confident and distracted at their jobs.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC The buzz has been reverberating for a while about Cabin in the Woods, the rare literate, fresh take on the horror genre, and one that is rife with surprises. We don’t need to discuss those surprises to discuss the film, but from the opening scenes we know that the five young college students (two couples and a goofy sidekick) who are headed to a rural cabin are somehow connected to a pair of bantering government workers (Richard Jenkins & Bradley Whitford) who seem a little too confident and distracted at their jobs.

By design, Cabin in the Woods is like a hundred other horror films but it is also like Wes Craven’s 1996 pop classic Scream, in that it is a dissection of the genre as a whole. Director and co-writer (with Joss Whedon) Drew Goddard cut his teeth on the show Lost and its characters here similarly spend much of the film’s running time trying to figure out the boundaries of their reality. It’s unraveling this puzzle that gives the film its kick, and if the frights delivered to the cardboard characters at the cabin (which includes Chris “Thor” Hemsworth) stop being truly scary, its the riddle that keeps you engaged.

That Cabin in the Woods is able to see its conceit through to the end, and keep us off-balance until the finale, is the biggest surprise of all. I don’t trust myself to say much more, and I’m not sure the film’s charm would survive a second viewing, but Cabin in the Woods is one of those true “audience films” that playfully whips up the theater in its engaging mayhem. If you have even a passing interest in the horror genre, get yourself to a theater while the film is still drawing a crowd with which to share its witty thrills.

– – – – – – – – – –

Undeniably affecting, the much-discussed documentary Bully has already received mountains of praise for bringing attention to the issue of bullying among the youth. It’s an issue that draws strong emotions and reviewers, who seem eager to throw their support to the anti-bullying campaign as part of their glowing reviews. But analysis of the actual film, and its stunted perspective as a tool to raise awareness, seems to have gotten lost in the shuffle. Bully certainly is an emotionally exhausting document on the issue but it is not shy about resorting to a bully’s tactics to make its point.

Shot without narration and with only the barest of explanatory titles, Bully immerses us into the lives of five different case studies, mostly  Southern and rural, all apparently working class. For the great majority of the film we merely follow helplessly as the kids suffer and recount the bullying they receive on their way to, from, and during school. Seeing the actual footage of kids being assaulted and humiliated is tough enough, but the adults’ blundering and oblivious attitudes give Bully an extra, psychological twist of the knife. Just as Christians were given the grueling gore-fest of Passion of the Christ to express their devotion, people concerned about the issue of bullying are rewarded with an emotional horror show that carries the blunt force of an hour-and-a-half of security camera violence. It’s like releasing a 90 minute film depicting a rape, and touting its worth as a teaching tool.

Southern and rural, all apparently working class. For the great majority of the film we merely follow helplessly as the kids suffer and recount the bullying they receive on their way to, from, and during school. Seeing the actual footage of kids being assaulted and humiliated is tough enough, but the adults’ blundering and oblivious attitudes give Bully an extra, psychological twist of the knife. Just as Christians were given the grueling gore-fest of Passion of the Christ to express their devotion, people concerned about the issue of bullying are rewarded with an emotional horror show that carries the blunt force of an hour-and-a-half of security camera violence. It’s like releasing a 90 minute film depicting a rape, and touting its worth as a teaching tool.

Critics have actually applauded the film’s strategy of leaving out the voices of any experts who might be able to shed some light on the psychological and socio-economic forces that lead to bullying, as if such mundane things as facts would taint the purity of the film’s power. This approach leaves important ideas unexplored. Is bullying on the rise? Doesn’t it happen in wealthy enclaves as well? And also, didn’t the cameraman feel any need to intercede in an incident that crosses the boundaries from childhood teasing to potentially dangerous assault?

Most glaringly, the problem of bullying does not stem from the victims, it stems from the people doing the bullying. The action of the bully, not the victim, is the root of the problem yet the film does not contain a single interview with any of the many kids seen bullying in the film. A bully doesn’t need increased insight into his victims to stop bullying, he needs increased insight into himself. However, Bully has no time for an individual or a program that has successfully confronted bullying, preferring instead to give the film whatever momentum it has by continually raising the bar on the injustices these children face.

Then just what is the purpose of this bitter pill of a film? Certainly our sympathies are with the kids very early on, there is no “pro-bully” stance that needs to be disproven. No, this film seems designed to wrench our emotions, while containing almost no information on what the viewer should do with their sense of injustice, despite a last minute balloon launch at the finale and vague affirmations that we can “take a stand.” I said the film give us “almost” nothing that we can do, because the film does end with an internet address for “The Bully Project,” which appears to have mounted a mini-industry of seminars in collaboration with Bully‘s release. It leaves a cynical taste, The Bully Project obviously believes it has some answers on how to stop bullying, but they’re dangling the film as a ghoulish wind-up before they’ll deliver their sales pitch.

– – – – – – – – –

Coincidentally, more kids will be seeing The Three Stooges this weekend than Bully, with one of the biggest bully stars in movie history, the head-cracking, porcupine-slapping, eye-gouging Moe. They’ve been threatening to mount a Three Stooges feature film for years now, ignoring the slim possibility that any actors could summon the perverse chemistry present in the original comedy shorts Columbia Pictures produced for nearly a quarter of a century beginning in 1934. The project kicked around for years (at one time threatening to unleash Sean Penn, Bencio del Toro, and Jim Carrey as the Stooges.) It finally landed in the Farrelly Brothers laps, perhaps as capable a hands as any, and while far from a masterpiece, The Farrelly’s have probably made as good a Stooges movie as we have any right to expect from a modern Hollywood studio. As a fan, I couldn’t help but groan at some of their decisions but to be fair I laughed a lot as well.

A frequent problem with these pop culture updates is that their original form suited them best, whether it was a 22 minute sitcom or an eight-minute cartoon short. The Farrellys seem to understand this and they have split the film into three “episodes,” each with their own title card that serves to cut the movie down into three interconnected shorts. The film uses the same sound effects as in the originals and even resembles the simple camera set-ups as its inspiration. The Farrelly’s decided to go with a Stooges origin story, one that is surprisingly similar to the Blues Brothers film. We see the Stooges as children arrive at an orphanage as babies, becoming real nuisances by the time they’re ten or so (the kids as Stooges conceit never quite gels). Still boarding there as adults, the Stooges are sent out into the world for the first time when the orphanage is in danger of being foreclosed.

A frequent problem with these pop culture updates is that their original form suited them best, whether it was a 22 minute sitcom or an eight-minute cartoon short. The Farrellys seem to understand this and they have split the film into three “episodes,” each with their own title card that serves to cut the movie down into three interconnected shorts. The film uses the same sound effects as in the originals and even resembles the simple camera set-ups as its inspiration. The Farrelly’s decided to go with a Stooges origin story, one that is surprisingly similar to the Blues Brothers film. We see the Stooges as children arrive at an orphanage as babies, becoming real nuisances by the time they’re ten or so (the kids as Stooges conceit never quite gels). Still boarding there as adults, the Stooges are sent out into the world for the first time when the orphanage is in danger of being foreclosed.

This leads the trio to familiar ground. Hospitals, golf courses, and fancy parties are once again prowled by the reckless trio, and the chain of calamities the Farrellys dream up are consistently amusing and occasionally hysterical. (I’m not sure why I found someone getting a bucket of water containing a sledge hammer thrown in their face so funny, but I did). Surprising touches abound in the original series and the brief sub-plot of Moe joining the TV series Jersey Shore follows that spirit, in a way that the film’s sneakier product placement (for beer?) does not. I think personal tastes might apply but I found Will Sasso’s Curly pretty serviceable (he has a similar grace to his bulky frame), Sean Hayes’ Larry surprisingly engaging (Hayes seems to both mimic and expand the character) while Chris Dimantopoulos fails to bring to life the complex figure of Moe. If there was any secret magic in the original Stooges it was Moe who possessed it. How else could he make a character who unrelentingly doles out unwarranted insults and physical abuse a childhood institution for decades?

Moe’s character is further undermined by the sentimentality the seeps into the film, an emotion that could not be more absent in the original shorts. Moe would beat up Larry and Curly but he kept them around out of necessity. But Moe sticking around these idiots because he loves them? That gives the three-in-a-bed routine a completely new spin. And how odd it feels to see the film close with the Stooges triumphant; Moe, Larry, and Curly rarely ended the as heroes, while is seems modern Hollywood comedies lack the imagination to end a story in any other way. Even with expanded crudity standards, the new Stooges are too soft-hearted to approach the original series’ profoundly anarchic edge.