RAMPART (2011, directed by Oren Moverman, 108 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK I thought it was an interesting move when film producer Edward Pressman issued a second, unconnected chapter to the 1992 film Bad Lieutenant, going from Abel Ferrara directing Keitel as a corrupt cop in gentrifying New York to Warner Herzog helming a tale of pain-wracked Nick Cage in post-Katrina Louisiana. Although unaffiliated to the Bad Lieutenant films, Rampart exists for the same reason: to provide a tough star vehicle, in this case for Woody Harrelson as a loose cannon cop in post-riot Los Angeles. Surrounded by an exceptionally strong cast, Harrelson pulls out all the stops, and while the film is never less than watchable, Rampart suffers because it refuse to let this dirty cop get too dirty to like.

Set in 1999, (when the real-life LAPD were amidst what became known as “The Rampart Scandal”) Officer Dave Brown is a trash-talking, hard-drinking patrolman who is held in growing scorn by his own department. He takes drugs, sleeps around with strangers and ex-wives, he’s disrespectful to his daughter, and he tortures suspects into giving confessions, yet he does it all with great wit and humor so we can’t help enjoy the ride. Conservatives may argue with the film emphasizing corruption in the police force but it is all delivered with a wink and a nod that lets the film’s cynical anti-hero escape most of our scorn.

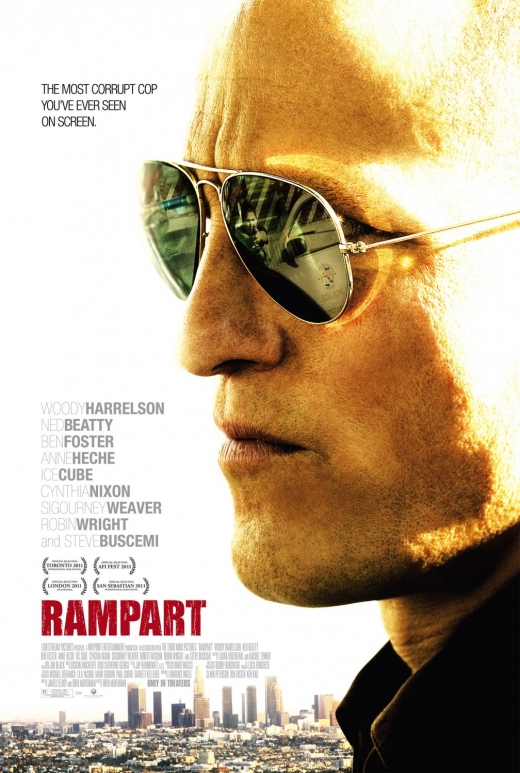

The film’s trailer actually flashes the uncredited quote “Woody Harrelson is the most corrupt cop you’ve ever seen on screen” but that’s a lot of hooey (or maybe we’re just hard to impress here in Philly, home of Frank Rizzo and all). Maybe I shouldn’t go on comparing it to Abel Ferrara’s incomparable Bad Lieutenant but that film dared to alienate us from Keitel’s shambling wreck, a cop whose moral compass had truly lost direction. Director Oren Moverman (who directed Harrelson ‘s Oscar-nominated performance in The Messenger) shows us the worst of Brown in the film’s beginning, then spends most of the rest of the film exonerating and excusing him. We hear him referred to as “Date Rape Dave” only to find out later that the nickname comes from his suspected vigilantism in shooting a “serial date rapist.” We hear him use racial epithets but that is counterbalanced with a fairly tender sex scene with an African American woman (well-played by opera singer/actress Audra McDonald.) And when it comes down to an actual robbery/murder that Brown premeditates, it is against another set of thieves sticking up an illegal card game. And he doesn’t kill them out of greed, it is those darn ex-wives who are driving him to desperation by asking him for more financial support then he can summon. While Harrelson’s Brown may be sliding into oblivion, he is doing it with such style, humor, and moral clarity that the character comes off a bit unreal in a setting that is stretching for realism.

Moverman has done daring and dark work as a screenwriter in the past (he adapted Denis Johnson’s druggy chronicle Jesus’ Son for the screen and collaborated with Todd Haynes on the Bob Dylan fantasia I’m Not There) so it is odd that this compromised work would be a collaboration with noir crime writer James Ellroy, a writer unafraid to explore the depths of human pathology and despair. And as screenwriters, the pair are fairly defiant about taking the story anywhere, the film has an ending that not only leaves Dave’s fate unresolved, but it hardly even locates a dramatic idea to close on. Yet Rampart remains at least mildly compelling throughout, since Harrelson rarely gives anything but his all in a role and the rest of the cast make the most of their wound-up characters. Anne Heche and Cindy Nixon frown and slouch up a storm, Ice Cube badgers Dave as an internal affairs investigator, and Six Feet Under’s Ben Foster (reunited with Harrelson from The Messenger) has the juiciest scene-stealing role as a wheel-chair bound homeless addict who channels the soul of the street. Sure, it is all sordid, but it is amazing that such fare can so proudly tout itself as “edgy;” these days cable TV regularly dissects the world of cops and crime with more surprise, energy, and depth then we get from such indie prestige films as Rampart.