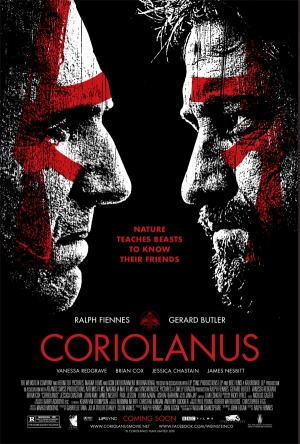

CORIOLANUS (2011, directed By Ralph Fiennes, 122 minutes, U.K.)

CORIOLANUS (2011, directed By Ralph Fiennes, 122 minutes, U.K.)

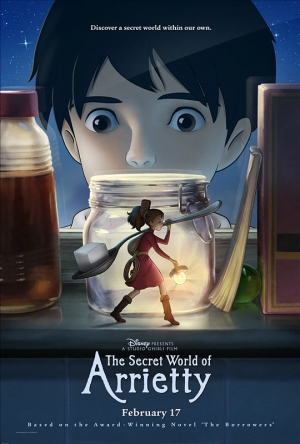

THE SECRET WORLD OF ARRIETTY (2010, directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi, 94 minutes, Japan)

BY DAN BUSKIRK

British thespian Ralph Fiennes has joined together with Gladiator screenwriter John Logan for an energetic adaptation of Coriolanus, one of Shakespeare’s decidedly second-tier tragedies. This is the first English language big screen version of the tale of the titular warrior/statesman who falls from favor with his people, and while Fiennes plunders the play for modern relevance he never solves the problem inherent in Shakespeare’s original work: Coriolanus is just too despicable to rouse the sympathies of modern audiences. It’s no surprise that Ruth Franklin of the Conservative bulwark The New Republic recently wrote a piece defending the character of Coriolanus, he’s a perfect hero for today’s Rand-ian one-percenters.

Set in modern times, TV news reporters speaking in iambic pentameter set up the story of the general Caius Martius (Fiennes) who is awarded the name “Coriolanus” for his bravery in battle. Framed by news footage of panic in contemporary Serbia, Coriolanus earns the contempt of his people by denying them bread while keeping silos of grain. Coriolanus imperiously confronts the mob, telling them that if they are not soldiers that do not deserve to eat. With strings pulled by the Senator Menenius (Brian Cox) and his power-hungry mother Volumnia (Vanessa Redgrave), Coriolanus is recruited to join the Senate, but the hatred he has stirred up in the rabble forces him from the city, and he ultimately finds common cause with his former enemies.

Fiennes the director takes no chances that you’ll be bored by the wordy, ancient dialogue, and the hand-held camerawork (from Barry Ackroyd, who has collaborated on many of director Ken Loach’s gritty dramas) and the modern setting establishes an authentic atmosphere of the here and now. Fiennes, has often seemed fussily-inert in films since his breathtaking turn in Schindler’s List 15 years ago, but here he radiates a ferocious, barely-contained presence as the gore-smeared general. His freshly-shaven dome brings to mind Brando’s Colonel Kurtz from Apocalypse Now, yet another warrior driven mad by war.

But the general’s rage grows monotonous over the course of two hours. Coriolanus is not the reflective Hamlet or the ambitious MacBeth, two characters torn by their drives and desires; in fact he is a man untainted by doubt. Coriolanus was of course written a couple centuries before the Age of Enlightenment, and the lead character’s disdain for the suffering of his people is a product of a mindset that has no comprehension of democracy. As it was written, the tragedy is that Coriolanus is a wise leader who has his hands tied by the ignorant masses. The general’s authoritarian streak leaves the play open to charges of embracing Fascism (Coriolanus was actually banned in Occupied Germany post-WWII for just that reason), and muddies the narrative as the general’s final comeuppance seems less a tragedy than “just desserts.”

Still there is much to enjoy in even a “non-masterpiece” by Shakespeare, especially the rich language and lingering questions the piece raises. And how sweet it is to have a relatively-unheard play, unmarred by overly-familiar passages and yet full of memorable verse in which to wallow. Redgrave and Cox, unsurprisingly make the most of their parts; Cox’s humorously purrs about the general, “There’s no more mercy in him than milk in a male tiger.” As for lurid subtext, you have Coriolanus’ wife (an ineffective Jessica Chastain) backing out of the room while watching the sensual care in which his mother tends to the general’s wounds. The film carefully develops what feels like Coriolanus’ most intimate relationship, that is with his nemesis, the Volscian General Tullus Aufidius (a game Gerald Butler.) They share a murderously-thrilling homoerotic dance, as the they clutch, slash, spin, and groan through a vigorous brawl amongst a destroyed housing complex. Their final meeting will be the film’s closing scene, and while time may have overturned the audience’s sympathies for these characters, The Bard is The Bard because he knows he to kick out your guts in a climax. It is a commendable achievement that Fiennes has returned this ancient play to a popular audience.

– – – – – – – – – – –

One never knows what they’re in for when they sit down in a theater seat, but few studios so consistently delivers the goods than Studio Ghibli, home of  Hiyao Miyazaki, director of modern classics like Spirited Away and My Neighbor Tortoro. The Secret of Arrietty (written by adapted by Miyazaki though directed by his protégé Hiromasa Yonebayashi) seems slightly second-tier in comparison to the phantasmagorical imagination of Miyazaki best works, yet even Ghibli’s second-tier productions tend to outclass the rest of the field of animation.

Hiyao Miyazaki, director of modern classics like Spirited Away and My Neighbor Tortoro. The Secret of Arrietty (written by adapted by Miyazaki though directed by his protégé Hiromasa Yonebayashi) seems slightly second-tier in comparison to the phantasmagorical imagination of Miyazaki best works, yet even Ghibli’s second-tier productions tend to outclass the rest of the field of animation.

Based on the popular kid’s novels The Borrowers by Mary Norton (whose work was the inspiration for Disney’s Bedknobs and Broomsticks), the story follows the fourteen year old Arrietty and her mother and father, who at two inches tall live beneath the floorboards of a rural home. Arrietty and her father adventure nightly to quietly scavenge the little that they need to get by but one day Arrietty is discovered by David, a sickly teenager sent to his Aunt’s home to recover from some unnamed malady.

Arrietty’s pacing is what really made it stand out for me. After a decade of Pixar wannabes and their rapid-fire pop culturally-dense gags, how foreign this quiet and detailed story seemed. The story’s urgency still kept the packed little audience rapt but how extravagant it seemed to allow the theater to be filled with nothing but the sound of crickets while Arrietty silently searches the jungles of the back yard. Carol Burnett as the voice of the suspicious housekeeper hits a bit of a shrill note, but The Secret of Arrietty is so arrestingly animated and expertly told that the childless should be tempted to borrow a kid and go see Studio Ghibi demonstrate the spectacular state of the art.