Tom Waits has become the secret handshake of cool — either you know it or you don’t, and after 20 albums, if you still have to ask you’ll most likely never know. Me? I’m a lifer. True story: Back in college I borrowed 1985’s Rain Dogs from the public library and got so lost in its lurid tales of the depraved, the derelict and the dispossessed camping on the wrong side of the tracks in Reagan’s Morning in America that I didn’t return it for a year and a half.

When I finally brought it back, I was banned for life. All told, it was worth it. I mention all this because Bad As Me sounds like welcome echo of Rain Dogs‘ spellbinding urban magic realism. Both albums are fulcrums effortlessly balancing all that has come before — the-piano’s-been-drinkin’ drollery of the Asylum years and the cinematic sweep and lump-in-your-throat sentimentalism of the Coppola soundtrack years — with all that comes after: the creepers and the weepers, the keepers (Bone Machine, Mule Variations) minus the sleepers (Alice and Black Rider).

We start off on a runaway downtown train, careening through the through the slaughter houses and gin joints of “Chicago.” Then we’re wading through the fevered, hoodoo swamps of “Raised Right Man.” On “Everybody’s Talking At The Same Time” we’re tooling down the lost highway of some forgotten David  Lynch movie in a vintage convertible with tail fins and Laura Dern and Nicholas Cage fucking in the backseat. “Get Lost” sounds like the theme song for some X-rated Elvis movie Jim Jarmusch should’ve directed, some Ann Margaret required. “Kiss Me” is easily the greatest non-silly love song since Barry met White. The warped, wild-eyed tango of the title track — powered by Rain Dogs alum Marc Ribot’s switchblade guitar — sounds like the greatest song Screaming Jay Hawkins never recorded. There’s a savage, sideways-marching post-war G.I. blues called “Hell Broke Luce” (“I left my arm in my coat!”) that manages the neat trick of supporting the troops while cursing the war pigs that pay them to kill and be killed.

Lynch movie in a vintage convertible with tail fins and Laura Dern and Nicholas Cage fucking in the backseat. “Get Lost” sounds like the theme song for some X-rated Elvis movie Jim Jarmusch should’ve directed, some Ann Margaret required. “Kiss Me” is easily the greatest non-silly love song since Barry met White. The warped, wild-eyed tango of the title track — powered by Rain Dogs alum Marc Ribot’s switchblade guitar — sounds like the greatest song Screaming Jay Hawkins never recorded. There’s a savage, sideways-marching post-war G.I. blues called “Hell Broke Luce” (“I left my arm in my coat!”) that manages the neat trick of supporting the troops while cursing the war pigs that pay them to kill and be killed.

Every song feels like it’s happening at the stroke of midnight, which is pretty much how it ends. It’s “New Year’s Eve.” The streets are streaked with dirty rain and neon and steam’s coming out of the ground like the whole goddamn town is about to blow. There’s gunfire and then sirens. We duck into a bar where nobody brings anything bigger than a fiver and run into the same crowd we met “In The Neighborhood” midway through SwordFishTrombones. It’s good to see the old gang again. It’s been a long time, and we’re all just a little bit older and a little bit colder. By now, everybody has figured out the dice were loaded and everybody knows the good guys lost. But at least we still have each other, until death do us part. Not that we have much choice. Thirty years after Reagan, it’s midnight in America and we’re all beautiful losers now. — JONATHAN VALANIA*

*

*

Bad As Me is Waits is at his alchemical best, lonely and lusty, loose and wild. Nostalgia’s not a dirty business here, the past gets dragged across a scratchy record and into the present, kicking and screaming and howling at the moon. The ghosts of an inscrutable America, at war with its own image, flicker in the rearview mirror before receding into the sleepless haze of history. Marc Ribot’s abstract twang makes the title track lurch with unhinged menace. “Back In the Crowd” sways heavy and gentle, evoking the slow-motion mirror-ball magic of an old, smoke-filled seaside dance hall. There’s the wheezing waltz of “Pay  Me” and the sultry “Kiss Me,” which sounds like it fell out of the back of 1978’s Blue Valentine, comes on like the flush of a slipped mickey. It’s not all boozy sadness — amidst the wailing and gnashing the joint still jumps and the house still rocks, horny horns honk and frantic guitars skitter like crazy cats on a hot tin roof. “Satisfied” may be the most badass Stones-homage committed yet in this post-wax age. Keef even lends his cracked croon to the dying-of-the-light duet “Last Leaf.” Don’t think twice about missing out on the bonus tracks: all suitably imperfect gems in the crown of this treasured troubadour’s storied career. Bad As Me is both an invitation and a dire warning: Heavens to Murgatroid, if you can’t stand the heat, get the hell out of the backseat and while you’re at it turn up the Wolfman Jack. — BRIAN MURRAY

Me” and the sultry “Kiss Me,” which sounds like it fell out of the back of 1978’s Blue Valentine, comes on like the flush of a slipped mickey. It’s not all boozy sadness — amidst the wailing and gnashing the joint still jumps and the house still rocks, horny horns honk and frantic guitars skitter like crazy cats on a hot tin roof. “Satisfied” may be the most badass Stones-homage committed yet in this post-wax age. Keef even lends his cracked croon to the dying-of-the-light duet “Last Leaf.” Don’t think twice about missing out on the bonus tracks: all suitably imperfect gems in the crown of this treasured troubadour’s storied career. Bad As Me is both an invitation and a dire warning: Heavens to Murgatroid, if you can’t stand the heat, get the hell out of the backseat and while you’re at it turn up the Wolfman Jack. — BRIAN MURRAY

*

THE MOST PERFECT SONG OF 2011: Apothecary Love

This old-timey charmer from The Low Anthem’s drop-dead gorgeous Smart Flesh, the follow-up to 2009’s blessed Oh My God, Charlie Darwin, made me smile all year long. It vibes like a summery cross between The Band’s Music From Big Pink and Beck’s Mutations – all mournful, moonlit country lilt and coal mountain melody waltzing matilda across the fruited plains and purple mountain majesties of the warm, narcotic American night. Its like old time country lemonade for your ears. The singer sounds like an Appalachian Cat Stevens telling it on the mountain, the harmonica wheezes like a far-off train whistle in the night and hearing that ghostly pedal steel  is, in my considered opinion, the closest you will ever get to God. Set in the olden days — when women wore bonnets, men wore britches and everything was sepia-toned — the lyric concerns two soon-to-be lovers that meet cute in an apothecary (sort of like an old-fashioned CVS). He’s just minding his own business, browsing the potions, pills and medicines, when he notices a sad-eyed lady of the lowlands. He quickly determines that she is tormented by the darkening voices in her head, the “conspiracy delusion that her boyfriend kept fed” and tells her that he’s got the cure for the shape that she’s in. Understandably she’s suspicious at first, but he assures his intentions are pure and all that he wants is to be the friend she so obviously needs. He has a voice you can trust. By the second verse, they are back at his homestead and she’s already feeling better. She shoots him with whiskey and then chases him with gin, she calms and comforts him, and stills the tremble in his hands — turns out she’s got the cure for the shape that he’s in. Cue scratchy, silent film footage of mortar grinding in pestle, train going into the tunnel, etc. All’s well that ends well, you would think. But by the last verse, she’s left him, he’s “reeling with that time-release feelin’” and so he heads back down to the apothecary, hoping to find a new cure for the shape that he’s in. In a word: perfect. – JONATHAN VALANIA

is, in my considered opinion, the closest you will ever get to God. Set in the olden days — when women wore bonnets, men wore britches and everything was sepia-toned — the lyric concerns two soon-to-be lovers that meet cute in an apothecary (sort of like an old-fashioned CVS). He’s just minding his own business, browsing the potions, pills and medicines, when he notices a sad-eyed lady of the lowlands. He quickly determines that she is tormented by the darkening voices in her head, the “conspiracy delusion that her boyfriend kept fed” and tells her that he’s got the cure for the shape that she’s in. Understandably she’s suspicious at first, but he assures his intentions are pure and all that he wants is to be the friend she so obviously needs. He has a voice you can trust. By the second verse, they are back at his homestead and she’s already feeling better. She shoots him with whiskey and then chases him with gin, she calms and comforts him, and stills the tremble in his hands — turns out she’s got the cure for the shape that he’s in. Cue scratchy, silent film footage of mortar grinding in pestle, train going into the tunnel, etc. All’s well that ends well, you would think. But by the last verse, she’s left him, he’s “reeling with that time-release feelin’” and so he heads back down to the apothecary, hoping to find a new cure for the shape that he’s in. In a word: perfect. – JONATHAN VALANIA

*

***

LYKKE LI

LYKKE LI

Wounded Rhymes

Tossing aside any narrow definition of Swedish pop, Lykke Li reprograms 60s girl band tropes— sweeping choruses and “He Kissed Me” innocence—for this bleaker age. The lesson: All those perfect, snowy mountaintops of the Nordic idyll resolve into dirty slush in the sunshine. The critics all seized on “Get Some,” with its Bo Diddley beat and stunning declaration—“I’m your prostitute, you gon’ get some” as the Rosetta Stone. But “Sadness is a Blessing” is the perfect pop masterpiece—music for girls to sing together and boys to listen to when no one is watching. That’s some real gender-smashing power right there. And two discs in, Lykke Li has no visible ceiling. A track titled “Unrequited Love”, sung by a Swedish pop singer over a spare, bluesy vamp sounds like a bad idea, conceptually. But in Li’s hands it swells up into a ballad Mick Jagger would gladly have carpet bombed on Beggar’s Banquet. A bitter, Stones-y howl from a 25-year old woman, unbound. — STEVE VOLK

*

*

THE BLACK KEYS

THE BLACK KEYS

El Camino

Once the album-opening Elvis-ian surf-a-billy of “Lonely Boy” lights your fuse, you will want to take the full ride in the Black Keys latest nitro burnin’ funny car of an album. On their last record, Brothers, The Black Keys dialed back the thick, freakiness of their trademark fuzzed-out biker bar choogle in favor of a smoother, white boy R&B biker bar choogle and wound up winning three Grammys and selling over 870,000 copies in the process. No wonder the mood of El Camino is celebratory, with less emphasis on the blues and soul music and more emphasis on white light/white heat, be it the T-Rex-ian “Gold on the Ceiling” or Stones-y stomps like “Run Right Back.” What you have right here is a straight out, pedal to the metal party record; a sticker affixed to the cover simply reads: “PLAY LOUD.” That’s sound advice, son. — COLONEL TOM SHEEHY

*

*

FUCKED UP

FUCKED UP

David Comes To Life

At nearly 78 minutes of full-throttle, full-throated punk rock, David Comes To Life is as relentless it is revelatory. As a rock opera about a lightbulb factory worker who finds and loses love over the course of four acts, it’s maddeningly convoluted and only semi-decipherable, especially given the growling, shouted vocals of the gruff Damian Abraham aka Pink Eyes. But Canada’s Fucked Up produced the year’s most purely exhilarating album, an adrenaline rush of triumphant hooks and triple-guitars (helmed by mastermind Mike Haliechek aka 10,000 Marbles) that owes as much to the Who as to Fugazi or Husker Du, whose Zen Arcade is its closest ancestor. It’s a fist-pumping moshpit of caterwauling voices, sweetened with sporadic female call-and-response vocals and extended instrumental passages. “To love and to lose has been my refrain – just when I think I’ve found hope I lose it again,” Pink Eyes barks at the beginning of “The Recursive Girl,” and that sums up the storyline. But by the end of the album, he’s singing the cliché that “love will never die,” and Fucked Up has you believing in the redemptive power of love and punk rock power chords. — STEVE KLINGE

*

*

JAY-Z & KANYE WEST

JAY-Z & KANYE WEST

Watch The Throne

Watch the Throne is the absolute height of hip-hop grandeur. If Sheek Louch and Roy Lichtenstein filmed a porno in the Guggenheim with some raunchy amputee prostitutes — that porno might achieve the same level of greatness Jay-Z and Kanye did with this one. Beats tend to switch midway through, lyrics about Fish Filets and blowjobs in mall restrooms are delivered with casual elan, guest appearances are both surprising and spare, the producer lineup reads like the Pro Bowl roster. This album is much, much more than part 2 of Kanye’s opus My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. It’s a new height for Kanye’s still-peaking ascendancy and a fitting denouement for Jay-Z’s soon-to-fade prominence. — MATTHEW HENGEVELD

*

*

THE DECEMBERISTS

THE DECEMBERISTS

The King Is Dead

The Decemberists went to the country for The King is Dead, recording it in a barn on an Oregon farm. Appropriately, the sound is rootsy and simple–folk tunes, Neil Young-ish country, REM style rock, and acoustic ballads. Gone are the prog rock and convoluted story cycles of past releases. The mix features harmonica, banjo, fiddle, accordion, pedal steel, and bouzouki, while the guitars are mostly acoustic and strummed, with Peter Buck adding his ringing guitar for a couple songs. Gillian Welch also contributes harmony vocals to over half the songs, adding country cred and mitigating Colin Meloy’s nasalosity. There’s even a barn and a horse on the back cover. The songs, which are shorter and more oblique than previous releases, reference nature frequently and focus on topics like family and community. In other words, it’s the opposite of The Hazards of Love. But what makes The King is Dead so good is the songwriting. All of the 10 songs have great melody lines and lyrics, and the ballads make the heart ache and taken as a whole, overwhelming evidence that Meloy may well be the finest rock songwriter standing at the start of the 21st Century. — MIKE WALSH

*

*

RADIOHEAD

RADIOHEAD

King Of Limbs

The strange mime-meets-epilepsy dance that bowler-topped Thom Yorke does in the video for “Lotus Flower” exemplifies the oblique dichotomies that King Of Limbs occupies: the twilight zone between funny and serious, between form and shape, between hue and color, between agony and ecstasy. Like so much of the music Radiohead has made in the 21st century, it sounds like it was made by paranoid androids — one part chimerical electronica, one part rock noir, one part accident and one part invention. The twitchy, inscrutable swirl of sonics is riven with anxiety and phantom menace — like we’ve rigged the Nostromo to self-destruct in five minutes and we’re racing for the escape pod amidst the steam and sirens, knowing fully well it will take us six minutes to get there — and offset by the minimalist operatics of Yorke’s vocals, which have the same effect as horses at a riot. It is his unique brand of genius that he can make every song sound like an accusation and an elegy all at once. What exactly he is on about remains open to debate and the particulars probably best left to the obsessive narratives and counter-narratives of message board exposition, but suffice it to say King Of Limbs‘ eight songs are ghost stories from inside the machine. — JONATHAN VALANIA

*

*

BEIRUT

BEIRUT

The Riptide

We all heard the clock ticking on Zach Condon—the precocious 19-year old super genius who demonstrated what a slight Brooklynite can do with a Balkan beat or Mexican funeral march. The conundrum: Once he had forced many thousands of hipsters to pretend they understand the finer points of a French chanson, wouldn’t his cultural mash-ups simply grow tiresome? But The Rip Tide, Condon’s third disc in the folkie outfit Beirut, suggests his gifts are more lasting. The obvious prize winner is “Santa Fe,” which rides a melodic progression reminiscent of David Bowie’s “Heroes” through airy realms of new world electronica and Old World pomp. The key takeaway from Rip Tide, though, is what his new, more spare arrangements reveal: Yeah, those martial beats still provide a rough kick in the pants. And those ringing horns, when they sound, suggest the romance of a foreign port on the horizon. But again and again, the songs on Rip Tide break down at some point, the exotic elements stripped away so all we’re left with is a melody and Condon’s warm croon, and still he has the power to wash us all out to sea. We thought of Condon as a kind of curator—a musician picking over the choice pieces of foreign cultures. But it turns out what he’s best at is writing songs. — STEVE VOLK

*

*

BILL CALLAHAN

BILL CALLAHAN

Apocalypse

Bill Callahan’s last album, 2009’s Sometimes I Wish We Were An Eagle, was one of the most inviting of his career. Full of strings and lush, careful arrangements, it’s the opposite of Apocalypse, which uses insistent, vaguely blues-based guitar vamps, both acoustic and electric, as the bedrock of a song-cycle about one man’s conflicted relationship with his country. Not unlike PJ Harvey’s Let England Shake, Apocalypse tackles this nation’s myths and delusions, triumphs and tragedies, dreams and disasters, but where Harvey is direct and vitriolic, Callahan is metaphoric and wry. The album is full of cattle drovers and other horseback riders; wide open roads and amber waves of grain stretching to shining seas; vexing questions of freedom and military service and commitments both personal and political. It’s also a very funny album, with wordplay that is easy to miss without a lyric sheet (“America! The lucky suckle teat, others chaw pig knuckle meat / Ain’t enough teat, ain’t enough t’eat, in America!”). We’re the lucky ones to have this album to chaw on. — STEVE KLINGE

*

*

MAYER HAWTHORNE

MAYER HAWTHORNE

How Do You Do

Despite being a geeky Jewish kid from the Detroit burbs, Mayer Hawthorne loves 60s and 70s Motown and soul music so much you would be forgiven for thinking his records were actually recorded back then. But Hawthorne makes no apologies on How Do You Do (his major label debut) for working in an earlier style. Instead, he wallows in the richness, joy, and romance of soul music, and delivers neo-classics in the process. And despite a healthy sense of humor about himself (those thick frame David Ruffin-esque glasses crack me up as do his videos), Hawthorne’s music is no joke. With a voice that recalls Smokey, the Temps, and the Delfonics, Hawthorne delivers songs on How Do You Do that immediately make the feet want to move. But be careful: these songs are so infectious, you could throw out your sacroiliac. — MIKE WALSH

*

*

ADELE

ADELE

21

“There’s a fire starting in my heart, reaching a fever pitch and it’s bringing me out the dark” goes Adele’s opening declaration on 21, and after the fact it sounds like prophecy because Adele exploded in 2011, providing comfort food for the soul for legions of mopey MILFS, weepy gay men and all the lonely people in between. Adele delivers these songs of love and hope and sex and dreams with a voice that is river deep, mountain high, with a wisdom, weariness and a fierce resolve far beyond her tender years. From the locomotive guitar chugging at the start of “Rolling in the Deep” until the final plaintive wails of “Someone Like You,” 21 floats like a butterfly and stings like a beeyotch. Her music was in perpetual rotation up and down the radio dial, and deservedly so, because 21 was the one album this year that people who don’t really like music all that much and those who can’t live without it could agree on. — PAUL STEENKAMER

*

*

RYAN ADAMS

RYAN ADAMS

Ashes & Fire

Ryan Adams is one of those love him or hate him artists. I go back and forth. Sure, he’s an inveterate attention whore, a piss-poor editor of his own creativity and a drama queen man-child too in love with his own legend. But when the planets do align, and The Fates allow it, he is also a top-shelf singer-songwriter in the grand tradition of the great denim bards of Laurel Canyon. Ashes & Fire is one of those occasions. It is not, as the growing consensus would have it, as good as 2000’s Heartbreaker, his previous high-water mark — it’s better. Much better. Reportedly clean and sober and happily married, Adams seems to have finally grown the fuck up. There is a master class precision to the writing and execution of these songs — an exacting attention to subtlety and nuance, a perfectly calibrated modulation of mood and dynamics — that simply cannot be faked. Some credit must go to producer Glyn Johns who has a long track record of catching lightning in a bottle. But also to Benmont Tench and his magic Hammond B3 as well as Norah Jones, who plays a mean piano throughout and harmonizes rather angelically on a few songs with Adam’s wife — who, I’d wager, actually deserves the lion’s share of the credit for Ashes & Fire’s becalmed gravitas. Because, unlikely as it might seem on so many levels, it would appear that Mandy Moore (yes, that Mandy Moore) has succeeded where so many have failed and finally made an honest man out of Ryan Adams. — JONATHAN VALANIA*

*

*

CULTS

CULTS

s/t

The duo of guitarist Brian Oblivion and vocalist Madeline Follin that comprise Cults have created a sound that is easy to listen to, but hard to put your finger on. Their self-titled debut is shot through with distinctive retro ’60s girl group sounds, lush period production, sunbeam melodies, and beautiful harmonies. Yet if you listen carefully, you realize that this CD is a bit darker than the music first implies, plus there’s the creepy gimmick of including bits of extant spoken word recordings from infamous cult leader Jim Jones. But somehow all that is offset by the finger snaps, hip-shaking maracas, and the chiming glockenspiel gives this CD’s darker flavors a light-hearted finish. — PAUL STEENKAMER

*

*

THE ROOTS

THE ROOTS

Undun

OK, so I gave this album a poor review just a month ago, but it is a critic’s prerogative to change his mind. Upon closer inspection, Undun is marvelous, especially compared to every non-Roots album that 2011 produced. The story-telling is vivid and postmodern, beginning with the violent death and ending with the not altogether unfamiliar life of a good man gone bad. Call it a concept album or a movie between your ears, but don’t say The Roots lack for ambition. While most hip-hoppers are still vying for a spot on Hot97, The Roots are shooting for a cotdam Grammy. The Roots aren’t in the realm of Lil’ B or Action Bronson anymore; Undun is boxing with contenders like Gillian Welch, Wilco and Alison Krauss. In that respect, Undun is a grand slam for the South Philly boys. — MATTHEW HENGEVELD

*

*

SHABAZZ PALACES

SHABAZZ PALACES

Black Up

With all the woozy synths, hash pipe sonics, and pinging dub echo, Black Up is possibly the most psychedelic album released in 2011, an achievement rendered all the more remarkable by the fact that it is first and foremost a hip-hop album. Headed up by Palaceer Lazaro (a.k.a. Ishmael Butler, a.k.a. Butterfly of beloved ‘90s alt-hip-hoppers Digable Planets), the mysterious Shabazz Palaces released two full-of-promise EPs last year, but their first full-length is a densely-layered, 36-minute masterpiece. In a year that did nothing but hype the teenage Odd Future’s juvenalia as rap’s destiny, it was a veteran nearing middle age who created its freshest sounds. Perhaps for some, that’s a cause for concern, but I’m too enchanted to worry. — BRYAN BIERMAN

*

*

tUnE-yArDs

tUnE-yArDs

W H O K I L L

The sound and scope of Merrill Garbus’ tUnE-yArDs project has continued to grow, displaying a notable shift between the first two albums. The brilliant debut, BiRd-BrAiNs, was recorded almost exclusively by Garbus on lo-fi equipment and free software. On her follow-up, W H O K I L L, the ukulele and expansive voice loops remain, but there’s a lot more toys to play with. Working in a pro-studio with many other musicians, Merrill and multi-instrumentalist/co-writer Nate Brenner litter the songs with afrobeat rhythms, fuzz-bass, and siren-like saxophones not unlike The Bomb Squad’s gritty production work. And where the debut was about sadness and heartbreak, W H O K I L L is filled with the anger that follows, perpetually swarmed with violent imagery. On “Killa,” Garbus soulfully warns, “all my violence is here in the sound,” backed by an ‘80s funk beat that keeps building until it falls in on itself—it’s a strange and scary mix, but like a car accident you can’t help but look. — BRYAN BIERMAN

*

*

GILLIAN WELCH

GILLIAN WELCH

The Harrow & The Harvest

The storied past — half-remembered, half made up — is invariably the purview of roots music, but few practitioners display a more uncannily authentic connection to those sepia-toned days of yore than Gillian Welch. It’s like she’s some long forgotten Carter Family offspring who died at birth and was reincarnated into now. That is one way of explaining the power and the import of The Harrow & The Harvest’s brand of American beauty. The other explanation would the inordinate talent and devotion of Welch and her musical (and life) partner Dave Rawlings. Together, their precisely picked melodies weave their way in and out of Welch’s vocals to frame a starkly haunting tableau of Appalachian life, highlighting themes of discontent, disconnection and a yearning to return to the warmth and safety of old homes sold off or shuttered or foreclosed on a long, long time ago. The slower tempo of this album, combined with the minimalist instrumentation, pushes the indelible vocal harmonizing of these two longtime collaborators to the fore. Her first album in eight years (Eight years! The Beatles entire career was over in eight years!), The Harrow & The Harvest is proof positive that some things are still worth waiting for in our instant gratification world and cements the duo’s position as the postmodern face of American folk music. — MEREDITH KLEIBER

*

*

JULIANNA BARWICK

JULIANNA BARWICK

The Magic Place

I remember in the early 1980s being swept up by the first few EPs of The Cocteau Twins, particularly the swirling atmospheres around Elizabeth Fraser’s voice (whose tone pretty much defines the over-used adjective “ethereal.”), but my interest waned over the years because as songwriters the Cocteau Twins were fairly uneven at best. Juliana Barwick has been dogged with comparisons to the Cocteau’s music since she came out of Brooklyn (claiming Louisiana heritage) back in 2006, but she’s bested their work by ditching pop songcraft altogether and instead just reveling in the church-y atmospherics of the sound itself. She builds her pieces around short, repeated melodies, looped vocals, and just the hint of piano, bass, or guitar, giving them the feel of hymns more than songs. Enya? No, more like those intimate Eno moments, with a peacefulness profound for being diametrically opposed to the mood of our times. — DAN BUSKIRK

*

*

NICOLE MITCHELL

NICOLE MITCHELL

Awakening

With its bland cover and its ungodly generic title, “Awakening” does little to alert you to the strength of the latest release from Chicago flautist Nicole Mitchell. A genre that sadly has the sturdiest of glass ceilings when it comes to women, jazz sadly has little time for anything but stellar female talents. Former president of the legendary jazz collective AACM (Artists of the Advancement of Creative Musicians) Mitchell is just that type of extravagantly talented figure. “Awakening” exhibits her mastery of composition, it is filled with tunes that reap emotion from a familiarity that shifts and morphs with an brilliantly exploratory intelligence. The band here is three-quarters of the Thrill Jockey group Frequency, with Tortoise’s guitarist Jeff Parker replacing reedman Ed Wilkerson and milking his electric’s mellow tone for fine gauzy effect. It is in the spirit of Eric Dolphy and Rahsaan Roland Kirk that Mitchell can evoke such strength and nuance from the simplicity of her instrument, and her band of Chicago-based heavy-hitters proves that they don’t need gimmicks to make memorable jazz records. — DAN BUSKIRK

*

****

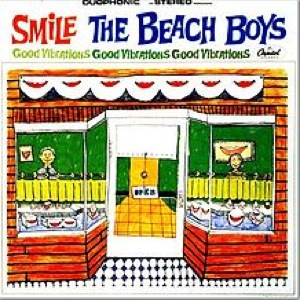

THE DUMB ANGEL

by

Jonathan Valania

Teenage symphonies to God. That’s the phrase Beach Boys auteur Brian Wilson used to describe the a heartbreaking works of staggering genius he was creating in the mid-’60s, when his compositional powers were achieving miraculous states of beauty and innovation even as his fevered faculties skirted the fringes of madness. With the 1966 release of Pet Sounds, The Beach Boy’s orchestral-pop opus of ocean-blue melancholia, Brian clinched his status as teen America’s Mozart-on-the-beach in the cosmology of modern pop music.

Less than a year later, he would fall off the edge of his mind, abandoning his ambitious LSD-inspired follow-up, an album with the working title Dumb Angel later changed to Smile, which many who were privy to the recording sessions claimed would change the course of music history. Instead, it was The Beatles who would, as the history books tell us, assume the mantle of culture-shifting visionaries with Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released a few months after Wilson pulled the plug on Smile. Meanwhile, Wilson sank into a decades-long downward spiral of darkness, exiling himself to a bedroom hermitage of terrifying hallucinations, debilitating paranoia, Herculean drug abuse and morbid obesity. While he would later recover some measure of his sanity, he would  never again craft a work of such overarching majesty.

never again craft a work of such overarching majesty.

In the wake of all the breathless hype for an album that was never finished, Smile took on mythical status, and a cult of Wilsonian acolytes sprang up as fellow musicians and super-fans tried to connect the dots into constellations and piece together a completed album from the bootlegs of recording session outtakes that have leaked out over the years. For decades, Wilson maintained a Sphinx-like silence, unwilling or unable to talk about the project, which only amped up the mystery surrounding the project. But given its central role in his precipitous downfall, it’s no wonder Wilson refused to even discuss Smile in interviews, let alone entertain repeated entreaties to finish and release it. Furthermore, he no longer had the Beach Boys’ golden throats to carry his tunes — brothers Carl and Dennis are deceased and his relationship with cousin Mike Love has devolved into acrimony and six-figure litigation.

Meanwhile, even with Wilson‘s protracted absence from the music scene, the dark legend of Smile was passed down via oral tradition and backroom-traded bootlegs to succeeding generations of pop obsessives, scholars and composers and hailed by many as the enigmatic “Rosebud” of popular music. Selected tracks from the Smile sessions — spectral, spooky, ineffably beautiful — released with 1994’s Good Vibrations box set only fanned the flames of obsession and lurid speculation. Like the mysterious leopard found frozen to death near the summit of the mountain in Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” everyone wanted to know how Wilson got that high and what exactly he was looking for up there.

Aided by the radical interventions of psychiatrists and a cornucopia of mood-altering and anti-psychotic medications — not to mention an empathetic support network of friends, family and business associates — Brian has staged an impressive comeback despite that fact that he remains a very damaged soul. For the last decade, he has delivered moving concert performances with an exceptionally fluent 10-piece band of new-school L.A. scenesters that is capable of replicating the sunbeam glories of those Beach Boys harmonies and recreating the orchestral pop glories of Pet Sounds down to the last ornate sonic detail.

The, in 2004, Brian shocked the music world with the announcement that he had finally completed his lost masterpiece with the aid of this crack touring band, re-recording the vocals and backing tracks and completing, with the help of his Smile-era lyricist Van Dyke Parks, the project’s half-finished songs. As welcome as news of this development was to Smile buffs, the end result was somehow less-than-completely-satisfying, like visiting a replica of an historic artifact in a museum (Not the actual bed that George Washington slept in, but an incredible facsimile!) The critical response was fawning, but smacked of the over-praise usually reserved for special Olympians, and as such ultimately fleeting.

Which is why the five CD box set The Smile Sessions will be the final word on Smile, separating once and for all rumor from fact, solving old mysteries, cracking the riddles of incompletion and providing closure for those that have pondered and puzzled over Smile‘s tragicomic legend for the last 44 years. Relying on cutting edge digital technology to assemble, assess and edit together the best and brightest moments buried in the more than 30 hours of Smile work tapes — which was a fool’s errand in the razor-and-scotch-tape analog era — and using the 2004 re-do as a guide for song selection and sequence, engineers Mark Linnett and Alan Boyd have assembled the closest we will ever come to a completed Smile on Disc One.

Which is why the five CD box set The Smile Sessions will be the final word on Smile, separating once and for all rumor from fact, solving old mysteries, cracking the riddles of incompletion and providing closure for those that have pondered and puzzled over Smile‘s tragicomic legend for the last 44 years. Relying on cutting edge digital technology to assemble, assess and edit together the best and brightest moments buried in the more than 30 hours of Smile work tapes — which was a fool’s errand in the razor-and-scotch-tape analog era — and using the 2004 re-do as a guide for song selection and sequence, engineers Mark Linnett and Alan Boyd have assembled the closest we will ever come to a completed Smile on Disc One.

Discs Two, Three and Four assembles rehearsal work tapes, embryonic early takes and alternate versions of the songs on Disc One. These outtakes are fascinating for the range of experimentation and innovation attempted here, as well the telling snippets of dialogue (“Are you guys feeling the acid yet?” Brian asks during an early run through the Gregorian chant of “Our Prayer”). Disc 5 contains 24 versions of “Good Vibrations,” enabling the listener to hear its evolution from quasi-R&B stomper to the trippy pocket-sized symphony that plays in perpetuity on oldies radio. Recorded over the course of nine months in three studios at a cost of $40,000 the song was at the time the most expensive single ever made. Serving as a bridge between Pet Sounds and Smile, “Good Vibrations” marks the beginning of Brian’s use of the modular composition technique that made the song both a deathless classic and an intimation of Smile‘s impending doom. Instead of tracking songs from beginning to end as he did on Pet Sounds, Brian recorded and re-recorded an endless series of interchangeable sonic segments that would be jigsawed together at the end. This technique would prove doable but daunting in the digital era — where point-and-click technology enabled the engineers to time travel back and forth across hours and hours of recording sessions in mere seconds and edit together otherwise incongruent musical passages with relative ease — but epic, laborious and, quite literally, crazy-making in the low-tech analog era of the late 1960s. In that sense, Smile was way ahead of its time, as Brian and his acolytes always claimed, if only because the technology needed to complete it simply didn’t exist in 1967.

But a few listens to the songs on Disc One would cause any neutral observer with a functioning pair functioning pair of ears to conclude that this music was way ahead its time sonically and thematically — a cinematic travelogue narrated by a psychedelic barbershop quartet fronting a cosmic Salvation Army Band, mapping the birth of a nation, the westward expansion of manifest destiny from Plymouth Rock to blue Hawaii, evoking all the weirdness and whimsy, the laughter and the tears, the triumph and tragedy in between — because it still sounds thoroughly modern, and for that matter altogether mind blowing, 44 years after its stillborn inception. *

*Originally published in issue #83 of Magnet magazine. Low Anthem portrait by Johnnie Cluney.