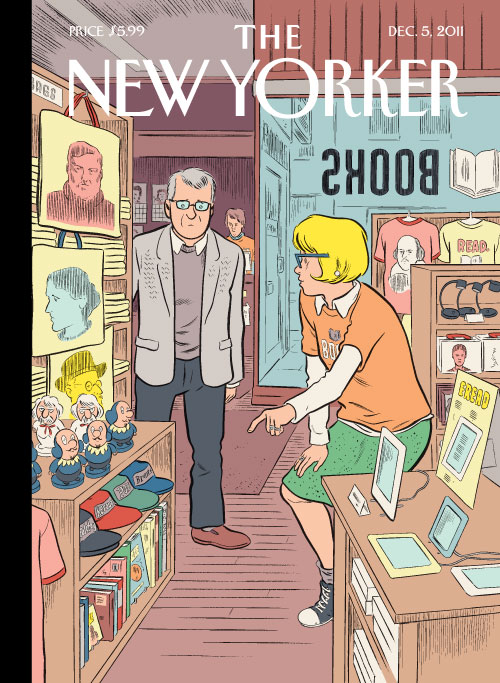

EDITOR’S NOTE: To mark the occasion of yet another swell New Yorker cover by Mr. Clowes, we are re-running our interview with him from last spring. Enjoy.

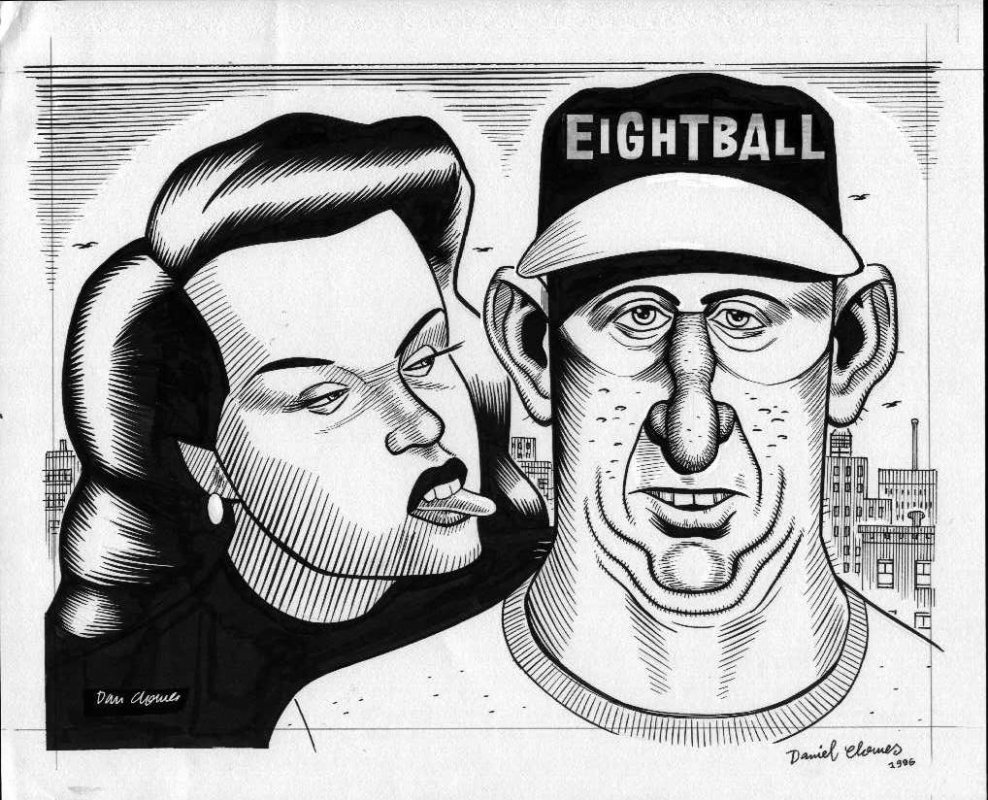

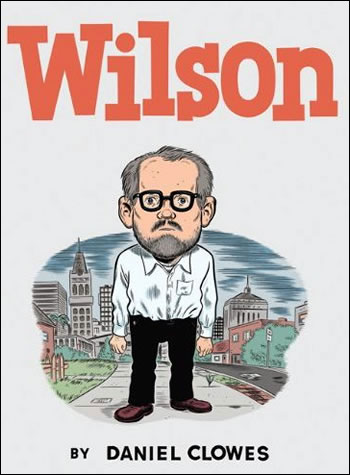

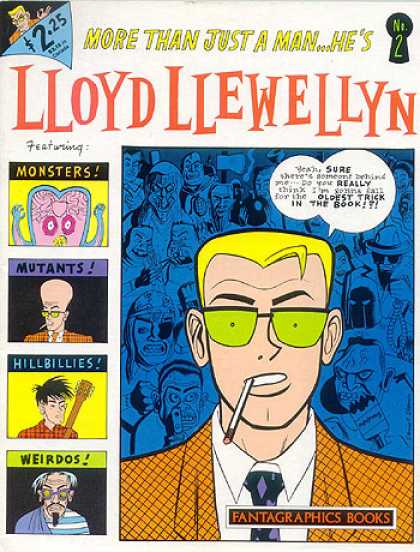

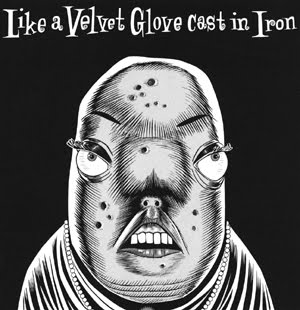

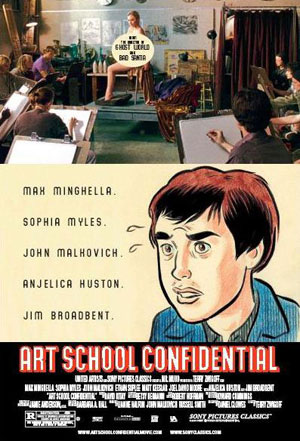

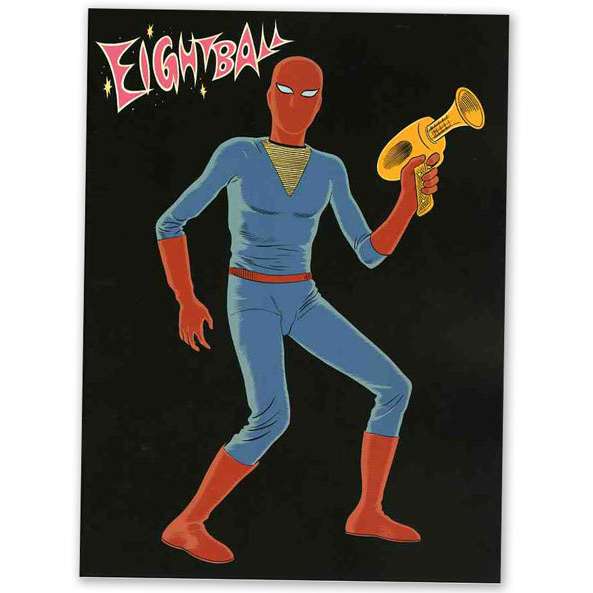

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA Daniel Clowes’ 30-plus-year career as a cartoonist/graphic novelist/screenwriter has seen some remarkable reversals of fortune. Back in the mid-80s, when Clowes was fresh out of Pratt and looking to take the graphic design/illustration world by storm, he couldn’t get art directors to return his phone calls. These days, post-Ghost World, the New Yorker and The New York Times plead with him to return their calls. When not busy cranking out darkly hilarious comic works like Eightball, Dan Pussey and David Boring, or illustrating Ramones videos and Supersuckers album covers, or working with Coke to create the infamous OK Cola anti-marketing campaign, Clowes forged a successful secondary career as a screenwriter, which resulted in an Oscar nomination for the screenplay to Ghost World. More recently he has focused on the long-form comic strip, investing works like Wilson and the just-published Mr. Wonderful with both his distinctive graphic imprimatur and a gift for story-telling and character study that rivals any of the big-wigs of contemporary fiction. Not bad for a form that heretofore aspired to little more than indulging the fantastical yearnings and hormonal angst of pimply-faced teenage boys. If Clowes is not careful he will wind up being remembered as the guy who made comics respectable. Long a fan of Mr. Clowes’ work, we got him on the horn to discuss recent work like Wilson and Mr. Wonderful along with Ghost World, Lloyd Llewellyn, Eightball, Jack Black, Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron, Thora Birch, Art School Confidential, Rudy Rucker, Raiders Of The Lost Ark, Michel Gondry and the advantages of male pattern baldness.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Daniel Clowes’ 30-plus-year career as a cartoonist/graphic novelist/screenwriter has seen some remarkable reversals of fortune. Back in the mid-80s, when Clowes was fresh out of Pratt and looking to take the graphic design/illustration world by storm, he couldn’t get art directors to return his phone calls. These days, post-Ghost World, the New Yorker and The New York Times plead with him to return their calls. When not busy cranking out darkly hilarious comic works like Eightball, Dan Pussey and David Boring, or illustrating Ramones videos and Supersuckers album covers, or working with Coke to create the infamous OK Cola anti-marketing campaign, Clowes forged a successful secondary career as a screenwriter, which resulted in an Oscar nomination for the screenplay to Ghost World. More recently he has focused on the long-form comic strip, investing works like Wilson and the just-published Mr. Wonderful with both his distinctive graphic imprimatur and a gift for story-telling and character study that rivals any of the big-wigs of contemporary fiction. Not bad for a form that heretofore aspired to little more than indulging the fantastical yearnings and hormonal angst of pimply-faced teenage boys. If Clowes is not careful he will wind up being remembered as the guy who made comics respectable. Long a fan of Mr. Clowes’ work, we got him on the horn to discuss recent work like Wilson and Mr. Wonderful along with Ghost World, Lloyd Llewellyn, Eightball, Jack Black, Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron, Thora Birch, Art School Confidential, Rudy Rucker, Raiders Of The Lost Ark, Michel Gondry and the advantages of male pattern baldness.

PHAWKER: Can you just identify yourself please?

DAN CLOWES: Daniel Clowes: Oakland, California.

PHAWKER: Terrific. Listen, before we get started, you and I actually go back a ways.

DAN CLOWES: Your name seemed awfully familiar.

PHAWKER: Oh, did it?

DAN CLOWES: Yeah.

PHAWKER: You probably don’t remember, but, in the early ’90s, I had a rock band called The Psyclone Rangers and…

DAN CLOWES: I do remember!

PHAWKER: Oh, awesome. And I convinced you to let us use one of your hilarious panels about the inventor relaxing at home with the sort of…

DAN CLOWES: Yeah, yeah.

PHAWKER: old timey masturbation device.

DAN CLOWES: Yeah, yeah. You know what? I’m actually putting together a monograph. So I’m going through all my old files and I came across it pretty recently.

PHAWKER: Awesome. Listen, do you have that digitized? Is there any way you could send that to me so we could include that in this interview?

DAN CLOWES: It’s in this humongous pile of stuff so I would have to look again. I’ll see if I can dig it out.

PHAWKER: Awesome. Anyway, that’s great. I’m flattered that you remember because, I mean, I’ve been a long time fan and was really pleased to see that you’d made it to the Big Screen. And I’ve been following you all along and I was just realizing when I was looking at your bio that I guess I kind of got in on… Well, I was under the impression that Eightball kind of went on a long time before I found it. But it turns out it was there from the beginning.

DAN CLOWES: Yeah.

PHAWKER: Anyway, enough reminiscing about the good old days. Shall we jump into the proper interview?

DAN CLOWES: Sure.

PHAWKER: Let’s just start at the beginning. So how did you get into this business? What prompted you to get into cartooning in the first place?

DAN CLOWES: Well, it wasn’t much of a choice. I mean, when I was a little kid, we didn’t have a TV. And I had a brother who was about 10 years older than me and he left a gigantic stack of old comics and science fiction magazines and all his teenage crap in my room. And for a four or 5-year old that was like my source of entertainment. So I would try to figure out my way through these comic stories not knowing how to read really. Just kind of absorbing the imagery and trying to imagine what was going on. From that time on, I was just obsessed with the language of comics and the weird mystery that those old comics have. My mother tells me that from the age of, I think, 4, I said “I want to grow up and draw comics for a living!” And most people have some crazy thing like that when they’re 4. They want to be a fireman or something and then they change their minds when they’re 6. But I stuck to my guns.

PHAWKER: You held onto the dream.

PHAWKER: You held onto the dream.

DAN CLOWES: Exactly.

PHAWKER: Ha ha.

DAN CLOWES: Living out the 4-year old’s fantasy.

PHAWKER: That’s incredible. Mister Wonderful, which I thoroughly enjoyed by the way, was originally serialized for The New York Times Magazine where it ran for about 20 weeks. That was a long way from the old Eightball days, which I used to find tucked away in the back book shelf of the local Indie record store next to probably some psycho-tronic film guide or something like that.

DAN CLOWES: And that was one of our more high-end places. I was talking about how, when I first began doing comics, the best we could hope for was to be sold at comic book stores. There was no way a real book store was going to sell comics at all. That was not going to happen. So we hoped we could get into a comic store, but comic stores were all, you know, super heroes and elves and trolls and all the stuff that those guys like. And so there would always be a box in the back of the comic store, like a cardboard box that just said “ADULT”, and they would stick our comics in there along with the elf pornography or the unicorn pornography; all that crazy weird stuff. So it wasn’t like you could tell any normal person where they could go buy your comics. There was certainly no Amazon or anything like that. It wasn’t like you were going to tell your girlfriend’s parents like “Yeah, go to the dingy comic store across town. There’s a box in the back marked “ADULT” and go through the really weird pornography till you get to Eightball. And there you are.”

PHAWKER: I mean I think you just answered my question which was: Did that experience make you feel legitimized in a way that previous publishing experiences maybe did not?

DAN CLOWES: Well, here’s the interesting thing: at the time when we were in that box, I would get 20 to 30 letters a week from people who were reading the comics and when I did the thing for The New York Times, there was literally no response at all. It was like it was invincible, you know. It was in the one magazine in America that people actually would read every week.

PHAWKER: Wow. And how do you explain that?

DAN CLOWES: It wasn’t just me. I talked to all the other cartoonists and the other writers and they all said the same thing. I think it had to do with just being so out of context that people didn’t know quite what to make of it, and even my biggest fans were like “I’ll just wait for the book.” They would miss a week. You know, not everybody buys the paper every week and after missing a week they think “Ahh, I don’t want to start reading it now that I don’t know what’s going on” and so it was sort of a failed experiment. And that’s why it doesn’t exist anymore, I think.

PHAWKER: Interesting. I am a regular buyer/reader of the Sunday New York Times and a huge Dan Clowes fan and I  completely missed it — and I always read the Sunday magazine.

completely missed it — and I always read the Sunday magazine.

DAN CLOWES: Ha ha, I hear that a lot. I never met anybody who said “That’s how I learnt about your work.”

PHAWKER: Yeah.

DAN CLOWES: And that was really my whole thought. I thought “Here I can expose myself to this huge audience.”

PHAWKER: Sure. Several million copies of it, right?

DAN CLOWES: Yeah …that had never seen my work. And I’m assuming that it’s sort of subliminally entered the brains of a few people who happened to skim over it a few times and they later saw my other work and something clicked, perhaps. But it was kind of remarkable how little effect it had.

PHAWKER: Yeah, that is shocking. It’s too bad that didn’t work out. I remember when they started doing that. I thought that was a great idea.

DAN CLOWES: I think if they had just given artists four or five pages per issue to do a complete story people would have read that. But nobody wanted to commit to some long thing where they had to remember stuff every week.

PHAWKER: Yeah, I think you’re right about that. Okay, moving on. I know you’ve discussed this often but let’s bring this up again. Why are you, or why were you, so opposed to the phrase “graphic novel” and do you still feel that way?

DAN CLOWES: I was opposed to it just because I thought it wasn’t going to work. I mean it’s an inaccurate term because all the stuff that’s described as graphic novel is things like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, which is not at all a novel unless you’re a Holocaust denier and call it fiction. And a novel is fiction and most of the stuff is non-fiction. So I thought it was kind of a sloppy term and I kept thinking, well somebody’s going to come up with great term for what these are and I also tried to think of something and all my friends who are cartoonists tried to think of something and none of us ever did. So we have given up, and now it’s almost like the words “graphic” and “novel” don’t matter. It’s “graphic novel” is something very specific to, if not an audience, then at least to people who work in book stores, and so that’s sort of the key. So I’ve given up. I find I just use the term without even thinking about it, whereas it used to make me grit my teeth every time I heard it.

PHAWKER: Yeah, maybe you were over-thinking it a little bit. I mean it’s sort of like The Beatles or Led Zeppelin; no one actually thinks about those names. If you think about it, they aren’t really very good.

DAN CLOWES: Right. The Beatles is a horrible name.

PHAWKER: It’s a terrible name, yeah. But they made it mean something else.

DAN CLOWES: Yeah, and that finally happened and I’m willing to go along with it at this point. Because, you know, any other name is going to sound really gimmicky and it would be a sort of bland name.

PHAWKER: Do you think the rise of the quote-on-quote “graphic novel” represents a dumbing-down of modern society? Or are we just naturally more visually-oriented than we are verbally-oriented?

DAN CLOWES: I think it’s a bit of both, probably. I mean it’s a very appealing medium and it was not served well for many many years in its history. There was not a variety of stuff for general audiences. But there’s no reason that it shouldn’t be a mass medium, at least as much as prose novels are. It’s something that 5-year olds are drawn to and adults can be drawn to for subject matters, interestingly enough. So I think there’s some reason that it’s caught on. You can certainly pick up a graphic novel and decide if you’re going to like it at a glance which you can’t do with a novel. You know, you can kind of look through it and see if the images appeal to you. You can kind of get a feel for it. It’s like being able to look through a movie without watching it.

PHAWKER: Yeah.

DAN CLOWES: Beforehand or something.

DAN CLOWES: Beforehand or something.

PHAWKER: Exactly. Much easier to engage with casually. I loved Wilson…

DAN CLOWES: Yeah, all the old Eightball fans love Wilson.

PHAWKER: I did love it. But, man, it was really bleak and brutal.

DAN CLOWES: Ha ha. That’s the idea.

PHAWKER: Well, perhaps you could speak of some of the motivations for the tone and the story lines…

DAN CLOWES: It kind of came out of a dark place in my life. I mean I had a sort of similar experience to Wilson in the book where my Dad was in the hospital on his last legs and that was really where Wilson was born. I just trying to amuse myself in the hospital and started drawing these sick little comic strips in my sketch book without giving it a thought. You know, it was really automatic writing and this character Wilson quickly emerged. So he came out of a kind of bleakness and when I got home I just couldn’t stop thinking about him and I found him really hilarious. I found that in every situation you put him in he would surprise me and that’s the kind of character you look for as an author. You look for somebody who will take you in directions you don’t imagine. So for any given strip I would start out with a little germ of an idea and he would take it off in his own direction. He really took over my life there for a while.

PHAWKER: On a related note, it occurs to me that you are incredibly unforgiving in your depictions of male pattern baldness.

DAN CLOWES: Ha ha. Well, that’s my curse. It actually doesn’t bother me that much. It’s one of those things that as a young man I thought, “Boy, if I ever lost my hair that would be the worst thing in the world!” Now I kind of like it. There’s something about it that marks you as a certain kind of old middle-aged guy.

PHAWKER: A wise man.

DAN CLOWES: Yes.

PHAWKER: A village elder.

DAN CLOWES: Right.

PHAWKER: Fair enough. Going back to the very beginning again. What was the inspiration for Lloyd Llewellyn?

DAN CLOWES: God, there wasn’t much, you know. I was, at the time, trying to get work as a magazine illustrator in New York and it was not going well. And so I, just to keep myself sane, decided to draw a comic. I hadn’t drawn a comic in quite a while and I just sat down and started drawing and I came up with a character off the top of my head in like 3 minutes. It was no thought at all. The only thought was that it was funny to have a character with all those Ls in his name. Back in the 60s, they had this thing in the Superman comics where they made a big deal out of all the double Ls. Characters like Lois Lane and Lex Luthor and Lana Lang. It was just this ridiculous thing. And so I thought “Let’s have the ultimate Superman character. A guy who’s got like nine Ls in his name. So that was really all I thought about and I just drew this guy who was sort of like the typical 50s detective kind of guy and made up this thing as it went along, never really intending to do much more with him. I sent that one story to a bunch of publishers hoping to get the one story published and I sent it to Fantagraphics and they called up and said “How would you like to do your own comic book?” which was nothing I even imagined in a million years was going to happen. And I was all excited about that. I kind of wanted to do more of a thing like an Eightball anthology comic and they said, “We think comics  only work if you have one character that you focus on, so we want it to be about Lloyd Llewellyn.” So I was sort of stuck doing it; too much of a neophyte to say “No! I don’t want to do that!” I just went along with it and quickly ran out of ideas after a few issues.

only work if you have one character that you focus on, so we want it to be about Lloyd Llewellyn.” So I was sort of stuck doing it; too much of a neophyte to say “No! I don’t want to do that!” I just went along with it and quickly ran out of ideas after a few issues.

PHAWKER: Although that, too, seems like a natural fit for an animated treatment or a movie treatment. Has there ever been any consideration to that?

DAN CLOWES: Somebody once wrote a horrible screen-play based on it that fortunately was never made back in the 80s. But, I don’t know, it’s certainly nothing that interests me that much. If somebody else wanted to do it I’d listen. I agree, I think it’s sort of a ball of things identified the best animated. It’s completely outside my realm of interest at this point.

PHAWKER: It is a long long time ago, isn’t it?

DAN CLOWES: 26 years ago.

PHAWKER: 26 years ago. Man.

DAN CLOWES: Yeah, it’s a lifetime.

PHAWKER: What was the inspiration for Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron? I couldn’t put it down and I couldn’t wait for the next one. I was deeply invested in that story. It seemed very David Lynch-ey which is partly what pleased me so much. Was he an influence or was that just a coincidence?

DAN CLOWES: I was very influenced by Eraserhead when it came out. That movie was a revelation to me. And the funny thing about Velvet Glove is that everybody always thought it was influenced by Twin Peaks because they are very similar.

PHAWKER: Right.

DAN CLOWES: But, Velvet Glove actually pre-dated Twin Peaks by more than a year and it was all figured out by the time that came along. So it was something in the air at that time. Really, it was about my first marriage in many ways, but I didn’t realize that as I was working on it. I was trying to write using really personal daydreams and actual dreams and just completely unfiltered things from my own tortured inner life that were all sort of bubbling to the surface. Then when it was all done, I sat down and read the whole thing in one sitting and realized that everything kind of correlated to moments in my first marriage. Although, obviously not literally just to all dream-like metaphors for things that happened.

PHAWKER: Do I have this wrong? Do I recall you talking about you smoking a lot of marijuana at the time, or no?

DAN CLOWES: No, I definitely wasn’t.

PHAWKER: Okay. Maybe I was just projecting.

PHAWKER: Okay. Maybe I was just projecting.

DAN CLOWES: I had a little phase where I smoked pot for like 2 months, but not enough to affect my work. I kind of just made it so I couldn’t work. I would get really tired and not do anything, so I stopped.

PHAWKER: So drugs never had any sort of creative impact?

DAN CLOWES: No, not at all. Not at all. I can’t imagine…

PHAWKER: Moving on. Can you explain for people that weren’t there in the early 90s the premise of the OK Soda campaign that you were commissioned for?

DAN CLOWES: Ha ha, yeah. It does seem ludicrous when you explain it. Coke decided at some point that they were going to try to market a soft drink to this new Generation X of grunge/Nirvana fans that was emerging as a demographic in the early ’90s. They hired this ad agency, Wieden & Kennedy, from Portland who have done a lot of really innovative ad campaigns and just sort of gave them free range to come up with something. They came up with this idea of doing a soft drink. The intent was just to sell it to make it like any other soft drink – there’s no real reason you should pick this one over any other. I don’t think it’s ever been done in the history of advertising or large corporate products. So they hired me and Charles Burns and a few other artists to draw, instead of happy characters who are excited to be drinking a soft drink, these blank dead-pan characters on the can that sort of represented the dull ennui of the average consumer. And it was really one of those things that I can’t believe actually made it into the stores. It never went national, it was only in test markets. These things actually were printed and actually existed. The one I was working on – I was sure it was never ever going to be released to the public. But it was released to the public and it was the biggest failure this side of new Coke that has ever happened. Any company that sunk millions of dollars into it did not make a cent. It turned out people don’t want to be told the truth. In advertising they kind of want to be lied to because it did not work at all. The audience they were aiming for were totally resistant to that so it hit no audience at all.

PHAWKER: Exactly. I mean it was essentially trying to affect the disaffected, correct?

DAN CLOWES: Right. Which, you know, was an ill-conceived idea. But, of course, there was also something really brilliant and deeply cynical about it.

PHAWKER: Well, I mean they’ve become sort of collector’s items now too. The extent art…

DAN CLOWES: Of course it’s got a huge following. I wish I’d kept more of the cans actually. The coolest thing I have is a face for an OK Soda machine, so it’s like a gigantic plastic vision of the face I drew.

PHAWKER: Oh wow.

DAN CLOWES: Like 6 feet tall.

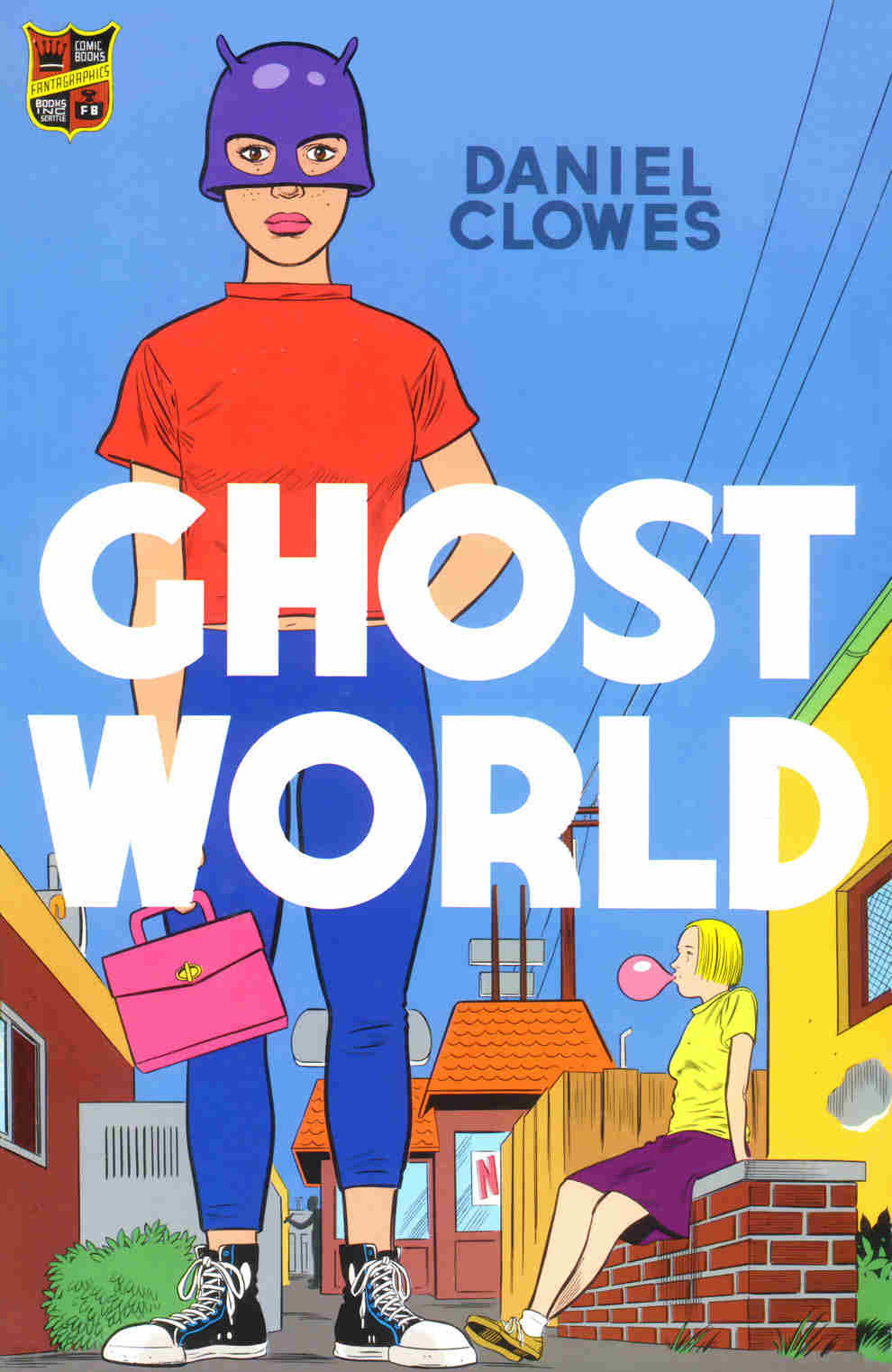

PHAWKER: Moving on. The protagonists of Ghost World are 2 teenage girls, which you are not now nor have ever been.

DAN CLOWES: Ha ha. Not that I recall.

PHAWKER: What prompted you to use 2 teenage girls for your protagonists? Were you, in a way, trying to buck the stereotype that comic books were largely read by males who are unable to connect with the opposite sex?

DAN CLOWES: I wasn’t necessarily thinking about that, but I’d felt like I’d been very male-centric up until then. You know, I’d done the Lloyd Llewellyn and Velvet Glove stories and then Pussy and all that stuff. I thought I wanted to do something different. I felt like all my characters were obviously stand-ins for myself, and people were reading into stuff and assuming it was autobiographical way more than I intended them to. So I thought I’d try to do something with characters that were not at all me and that nobody would mistake for me.

PHAWKER: So how did you get into the mindset of teenage girls? I mean, did you do some kind of research or were the characters really just you but with the gender transposed?

DAN CLOWES: It was a little bit of that, but it was mostly from knowing girls like those two. Knowing lots and lots of girls like those two. Especially my wife, my current wife, who I’d just met at the time. And just hearing her stories of when she was in high school and just kind of getting a sense of the way girls were in friendships. I was always a very quiet guy that girls kind of felt comfortable around and so I would just be there when they talked normally and they would forget I was there. So I felt like I had a sense of how they interacted that I’d never seen anywhere else. I couldn’t understand why there weren’t movies or TV shows where they showed girls interacting in the way I knew them to interact. So it was very easy to do it. Of all the books I’ve ever done, that was the one that took the least effort. It was just sort of, you know, channelling these two characters and writing down what they said.

PHAWKER: You strike me as someone who’s innately skeptical of Hollywood. What was your experience working on the Ghost World movie like?

DAN CLOWES: It was so far outside Hollywood. I mean that’s the thing; any of the movie stuff I’ve done is the equivalent of the Fantagraphics of the movie world. It’s people who have the same sort of mindset of being opposed to the main culture of Hollywood. We had our meetings with big studios where you are just sort of met with blank stares. You know, we had our share of horrible disappointments trying to raise money. For the most part, it wasn’t your typical thing where the studio wanted to re-cut the film. Luckily the film was so un-commercial from the get-go that there was really nothing they could do to ruin it. There was no way that they could re-shoot a few scenes and make it commercial. They knew immediately that it was not going to be a huge hit. Although it actually did very well, considering.

DAN CLOWES: It was so far outside Hollywood. I mean that’s the thing; any of the movie stuff I’ve done is the equivalent of the Fantagraphics of the movie world. It’s people who have the same sort of mindset of being opposed to the main culture of Hollywood. We had our meetings with big studios where you are just sort of met with blank stares. You know, we had our share of horrible disappointments trying to raise money. For the most part, it wasn’t your typical thing where the studio wanted to re-cut the film. Luckily the film was so un-commercial from the get-go that there was really nothing they could do to ruin it. There was no way that they could re-shoot a few scenes and make it commercial. They knew immediately that it was not going to be a huge hit. Although it actually did very well, considering.

PHAWKER: It did very well what?

DAN CLOWES: Considering that it was a completely unadvertised film that only showed on 150 screens at its height, it did very very well in theaters. It was considered a big success for an independent film.

PHAWKER: Yeah, I would agree. Now how did that contrast to your experience of working on Art School Confidential? Most of the reviews for that movie were quite unkind.

DAN CLOWES: Yeah. You know making a movie especially when you’re the screen writer is like 50% luck. It’s like with Ghost World, there were many many things that I thought weren’t going to work and the ball bounces the right way and suddenly it works. With Art School it was like everything bounced the wrong way; stuff didn’t work. So it’s a very careful tightrope walk and if you get it right everything kind of falls into place and if you get it a little off everything doesn’t quite gel. So it’s a weird experience to sort of be inside that and you kind of have a feeling that it’s going to go one way or the other, but you really can’t tell until it’s too late.

PHAWKER: Just a couple more questions here, Dan, and most of these are regarding film projects that you are connected to. For the sake of those not in the know, can you give readers the broad strokes of Death Ray?

DAN CLOWES: Well Death Ray is going to be my next book, first of all. It was comic book I did several years ago that’s never been reprinted that I consider maybe the best thing I’ve done. It’s a story of a teenage superhero set in the ’70s that’s going to be released in book form later in the year.

PHAWKER: It was the second to last Eightball, correct?

DAN CLOWES: It was the last edition of Eightball.

PHAWKER: Oh, it was the last one? Okay. I have it, by the way. I bought it.

DAN CLOWES: Oh, there you go. A few of you guys bought it. No, it sold out kind of immediately when it came out, but it’s been out of print now for 6 or 7 years.

PHAWKER: Oh, wow. Well you made us wait so long. It was a lot of hunger.

DAN CLOWES: Yeah, yeah. I just sort of never quite had time to put it together. I had to sit down and figure out how to make it into a book. But, anyway, that’s later in the year and there’s a movie version that I’m sort of talking about with the director, a guy named Chris Milk, at this point, which is very different from the comic. It’s sort of an alternative version of the comic in a way that Ghost World was.

named Chris Milk, at this point, which is very different from the comic. It’s sort of an alternative version of the comic in a way that Ghost World was.

PHAWKER: And Jack Black’s production company’s connected to this?

DAN CLOWES: Yeah, he came in and got me a deal to write the script and he’s involved kind of as a producer and there’s a supporting character that he would play in the film.

PHAWKER: And where is that in terms of development?

DAN CLOWES: We’ve got a script and I’m basically waiting until the director’s schedule is clear to meet with him and see what we can do from there. It sounds like he wants to do it later this year, but I try not to talk about any of that stuff because it all changes so drastically all the time.

PHAWKER: Right. Tell me, did you find transitioning into screenplay to be fairly effortless. I mean, what sort of things did you do to facilitate that?

DAN CLOWES: Well, it definitely wasn’t effortless. It took many many attempts to get anything even passable for Ghost World. The thing is when I write my own comics, I know how I’m going to draw them and I know how the story’s going to be told and so I have a sense of how things will work or not. But when you’re writing a screenplay, you’re then giving it over to somebody else and they have to understand what you’re talking about. So I find I have to be much clearer in my intent in writing the screenplays. That was a hard thing to learn; to write descriptions of things that people could actually understand so that there was no ambiguity about it, or at least lead them in the right direction. But in terms of putting together scenes that are propelled by visuals and dialogue, it’s got a lot of similarities to writing comics. But, you have a lot more leeway in writing a screenplay because you can change much much easier than if you’ve already drawn them.

PHAWKER: Now, you’re also attached to a film treatment of Rudy Rucker’s Master of Space and Time…

DAN CLOWES: You know, that was a project that I think, in 2005, I got together with Michel Gondry and we put together a whole prospectus for that film and we pitched it to a few studios. This film would cost $150 million and it would be a completely un-releasable art film that would make like $700,000. So we gave up on it. I mean we could either turn it into something commercial which meant starting from scratch or we could try and make it for no money which just wasn’t possible the way the story is written.

PHAWKER: Now were you already a fan of the book or had read the book?

DAN CLOWES: No, I had never heard of it. Somebody had sent it to Gondry many many years ago and he always wanted to do it. It would be a very funny and interesting movie, but it absolutely would not be a big blockbuster. You know, the character changes from a man to a woman like two-thirds of the way through for no reason, so you’d have to get a different actor to all of a sudden be the star of the movie. You know, most stuff that a studio would never go for.

PHAWKER: And how did you form this collaborative relationship with Michel Gondry?

PHAWKER: And how did you form this collaborative relationship with Michel Gondry?

DAN CLOWES: He had a girlfriend for a while who was a cartoonist and she kind of turned him onto all this stuff. I guess he’d read my comics; he had read Velvet Glove that was coming out. And he just thought I would be a guy who might be interesting to work with, so we met up and really liked each other.

PHAWKER: One last question, then, and that is: can you explain this Raiders [of the Lost Ark] project?

DAN CLOWES: It was three kids in Mississippi who made their own version of Raiders of the Lost Ark in the 80s and it was an incredible feat that took up their entire childhood where they re-shot the film shot for shot.

PHAWKER: Over many years, correct?

DAN CLOWES: Yeah, over like 8 years and it’s just one of these unbelievable human endeavors deserving of all kinds of fame and glory. But, of course it can’t be released because it’s the supreme copyright violation of all time. Several years ago, the studio wanted to make a film about these guys and about their childhood and about the making of this film, so I was called in to write a screenplay for it and I wrote something. And just as I was finishing, Paramount announced that they were going to release the new Raiders of the Lost Ark film. I guess it was the fourth one with Harrison Ford being like 85-years-old or whatever.

PHAWKER: Right.

DAN CLOWES: That came out a couple of years ago, and once that was in the works – once that was actually going to happen – they basically told us that there was no way they were ever going to make our film. They didn’t want to have anything out there that seemed like a comment on their big franchise or that could confuse anybody. Obviously it would have been a very small film and they just didn’t see any reason to grant us the rights to use Raiders of the Lost Ark if they had this big tent pole franchise out there. You know, every screenwriter has a thousand of these stories. They all write 50 screenplays that don’t get made and every one of them has a reason that it didn’t get made. Just some small conceptual thing that’s just not worth the hassle of trying to get it made; it’s not a big blockbuster kind of a thing.

PHAWKER: I take it you have seen this movie?

DAN CLOWES: Oh yeah, I’ve seen it many times.

PHAWKER: And…?

DAN CLOWES: Oh, it’s amazing.

PHAWKER: Really?

DAN CLOWES: Luckily these 3 guys have gotten quite a bit of press about their film and so they travel around the country and  if they appear in person and show the film they’re allowed to show it as a museum piece or something. It sort of skirts the copyright violation. They’ve traveled everywhere so just keep your eye out for these guys and they’ll show up in your town at some point.

if they appear in person and show the film they’re allowed to show it as a museum piece or something. It sort of skirts the copyright violation. They’ve traveled everywhere so just keep your eye out for these guys and they’ll show up in your town at some point.

PHAWKER: Amazing.

DAN CLOWES: And they’re great guys. They’re really what you’d hope for, for guys who make something like that. Just really good guys.

PHAWKER: Okay. I think that’s it. I was going to ask you what comes next but you already answered that with the Death Ray thing.

DAN CLOWES: Yeah, well I’m working on a Wilson movie too, which is the thing I’m most excited about, for the director Alexander Payne who did Sideways and all that.

PHAWKER: Wow. So where is that in the timeline of development?

DAN CLOWES: I’m working on the screenplay right now. [Alexander Payne] is working on a movie right now and when he’s done with that movie we’ll see if he likes this one.

PHAWKER: Excellent. Well, listen, thank you very much for your time.

DAN CLOWES: Sure. Thanks for calling.